- 464 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

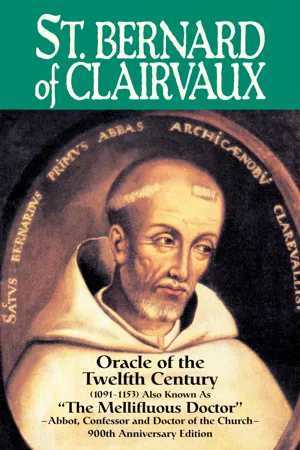

Abbot; Confessor; Doctor of the Church (1091-1153). In all history no other man so dominated his times and influenced its people. He prophesied; cast out devils; worked miracles; destroyed heresy; single-handedly healed a schism; launched a crusade; advised popes; guided councils (6); ended a pogrom; accomplished every mission given him--yet was always sickly; took no joy in the world or pride in his successes; and ever longed to return to his cell. A story to make you weep. 480 pgs;

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access St. Bernard of Clairvaux by Abbe Theodore Ratisbonne in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Teologia e religione & Denominazioni cristiane. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Teologia e religioneSubtopic

Denominazioni cristianeFifth Period

APOSTOLIC LIFE OF ST. BERNARD, FROM THE PREACHING OF THE CRUSADE UNTIL HIS DEATH. (1145-1158)

Chapter 34

IDEA OF THE CRUSADES—STATE OF CHRISTIANITY IN THE EAST

HAIL, Holy Land! Land of human sorrows and divine mercies! Land of prophecy, country of God and man, our eyes now turn towards thee. At thy very name we feel an irresistible emotion, and the depths of our souls re-echo the accents of the royal psalmist: "O Jerusalem, may my right hand perish, if ever I forget thee!"

But if we would speak worthily of Jerusalem, we must borrow the language of St. Bernard: "Hail, then, holy city, city of the Son of God; chosen and sanctified to be the source of our salvation! Hail to thee, dwelling place of the Great King, whence have emanated all the wonders of ancient and modern times which have rejoiced the world! Queen of nations, capital of empires, see of patriarchs, mother of prophets and apostles, first cradle of our faith, glory and honor of Christianity! Hail, promised land, once flowing with milk and honey for thy first children, thou hast produced the food of life and the medicine of immortality for all future ages. Yes, city of God, great things have been spoken of thee!"

Although now dead and withered, Jerusalem, like the prophet's bones, seems still to possess the virtue of giving life to the dead who touch her ancient remains. Her name, like the name of God whence it is derived, is invested with a hidden power, which at certain periods manifests itself like the electric spark and diffuses a sacred emotion throughout every land; and when the world goes astray, when it becomes exhausted, or slumbers in the shadow of death, this life-giving name awakens it, and the angel who descends into the pool of the holy city stirs the springs of life, and pours the heavenly sap once more through the veins of the human race.

There has never been any great idea, or first principle, or heavenly inspiration, which has not arisen in the Holy Land before its diffusion throughout the world. There, in the beginning, flowed the tears and the blood of sinful man; there, under the mount of skulls,* are laid the remains of Adam and those of the mother of the living. Melchizedek came there to offer the sacrifice of future reconciliation; and under that high-priest's footsteps, according to the eternal decree, arose Salem, the city of peace. The three races of mankind—the descendants of Shem, Ham, and Japheth—each in its turn mingled their ashes with those of the father of all men; and thus around the first human grave, the primitive altar of mercy, was found the sacred field of the dead—that vast cemetery of the sons of men, which gradually enlarged its limits into the uttermost parts of the earth. On this mystical altar flowed the blood of beasts, the blood of man, and the blood of God; and from the summit of this altar, on the Holy Mount, where Christ consummated His sacrifice, Divine grace flowed forth upon the dead and watered the dust of man, which will one day revive again.

All the nations of the world appear to have laid claim to the Holy Land; for it has been possessed, or occupied in turns, by the principal people of ancient and modern times. From time to time it has been inhabited by new tribes, and it is by the flux and reflux of their blood that Jerusalem, the very heart of the earth, nourishes the pulses of her mysterious existence. There can be no doubt that the Crusades, which are the great drama of modern history, form a link in this long chain of mysteries. To see in these wars nothing but the enthusiasm of a few warriors rushing to the deliverance of a sepulchre, would be to strip their history of its leading idea, and to overlook in the plan of Providence one of the most magnificent developments of the work of Christianity.

We have already said that in the history of man there is an order of invisible things in which the origin and last consequences of events often escape our investigations. While we are in this life we can only perceive the reflections and secondary effects of hidden causes; and, according to the apostle's doctrine, Christian science should be exercised rather on great and permanent realities than on passing phenomena; yet, were we only to judge of the Crusades by their visible results, we must allow that they were the expression of a sublime idea, and a kind of Divine necessity in some sort, which alone could have produced such great results.

It is not our object to enter into the details of this phase of our history. Other historians have recounted the exploits, the labors, the conquests, and the striking vicissitudes of the Christian heroes of that age; but it is fitting that, on entering upon this province of history, we should bear witness to the spirit which animated the Holy Wars, and the immense influence which they exercised upon Christian civilization.

In the first place, the question decided by the Crusades was not whether the Holy Sepulchre should belong to the disciples of Christ or the disciples of Mahomet; but the dispute was as to which of these two religions should possess the sovereignty of the world; this question was carried before the tribunal of the Holy City.

The formidable race of the Turks had established their empire over all the East, and from thence they threatened an invasion of the West. The nations of Europe, weakened by the dismemberment of their territories and their civil dissensions, trembled at the approach of the waves of this impetuous torrent. How could its onward progress be arrested otherwise than by the union of all the people of Christendom in one universal barrier? But, like all great undertakings, such a concourse and general stirring of nations could only be effected under the influence of a religious idea. The divine breath of religion only possesses the power of inspiring all men with one common sentiment, uniting them in one thought, and kindling among them a universal flame of generous enthusiasm.

The human mind at that period was doubtless unable to comprehend the sublime and vast ramifications of this great idea; man is almost always the blind instrument of a work which surpasses his understanding; the seed that he has sown can only be revealed by its fruit. The Crusaders, in their warlike ardor, aimed only at the deliverance of a sepulchre, and they were the deliverers of the world. But it was fitting that the essential idea of the Crusades should be displayed in all its simplicity, in order to be received and understood by the intellect of the age. The object in view was to rescue from the devil that sacred land above which the heavens had opened to give testimony to the Son of God. This was clear to the capacity of all, and the magical influence of this divine idea captivated the whole of Christendom, and revived its faith. The first result of this movement was a spirit of union among the nations and a wonderful harmony of sentiments, thoughts and interests, which unexpectedly put an end to all religious dissensions, political disturbances and civil wars. In the next place, as a natural consequence, followed the exaltation of the Papacy, which always resumes its place at the head of human affairs when the spirit of concord is to be revived among the nations. The Crusades alone gave to the Holy See more weight and influence in the affairs of the world than any doctrine, theory, or triumph by sword or word, before or since; and this central influence and great preponderance which it possessed was the mainspring of the development of the Middle Ages, and of the civilization of future times.

How can we but admire the power which thus called together a hundred nations and united them in one common brotherhood? Only a century before this time it was a difficult matter to collect an army of five or six thousand men. It was in the heart of this great Christian army that the influence of the Head of the Church resumed its ascendency over Catholic unity; add to this consideration the magnanimous virtue to which the Holy Wars gave birth; and if we even look at the matter from another point of view and reflect on the number of idle and degenerate Christians which the nations of the West poured forth into the East and the universal purification of the Church which ensued, we shall discover in the Crusades a new series of inestimable advantages.

This purification of the Church was not only moral and material, but it was chiefly manifested in the sphere of the intellect. In the preceding chapters we have seen how great was the fermentation of the public mind; the exuberance of human thought overflowed on every side; and if, at that period, the energetic activity of reason had not been subdued by a higher attraction, it would have swallowed up civilization in its infancy, and Europe would have relapsed into the darkness of barbarism. And from the intellectual point of view we may see one of the most extraordinary and immediate effects of the Crusades. The name of Christ, preached everywhere with the authority of faith, imposed silence on the discursive exercises of human reason. The remembrance of the holy places, where the mysteries of divine love had been accomplished, revived Christian piety in the minds of men; fruitless discussions gave place to tears of compunction, and to the vain disputes of feebler times succeeded a spirit of active energy, the distinguishing characteristic of the ages of faith. It would be difficult to conceive what the fate of Europe might have been if the Holy Wars had not opened a new course to the development of the human mind. The progress of civilization was much more endangered by the errors of reason than by the invasion of barbarians; and we are unable to determine which would have been the greatest misfortune for the Catholic world, the triumph of Mahometanism or that of heresy. The Church had to encounter the united attacks of these two adversaries at the same time; the efforts of both were defeated by the Crusades; and the preachers of the Holy Wars were so filled with the consciousness of the double mission they had to perform, that their words were equally directed against heretics and infidels; the Crusaders themselves spontaneously turned their arms against both these enemies.

It is certainly true that the soldiers of the cross were not always guided by the spirit of God, or influenced by justice, charity, and truth; we do not pretend to deny the monstrous abuses which too often disgraced their enterprises. But, in this place, the only important point for consideration is the great idea which predominates over all these questions; and it is rather by this idea than by the facts which resulted therefrom that we must judge of the man whose fiery eloquence aroused the spirit of the Crusades.

Half a century had hardly elapsed since the conquest of the Holy Land by Godfrey de Bouillon; and the preservation of this new kingdom by a mere handful of Christians seemed to be even more miraculous than the conquest itself; in fact, all the efforts of the many formidable enemies who surrounded them had proved unable to dislodge them. The Franks of the East, trusting in their acquired rights and full of faith in the future, lived on from day to day, without anxiety as to the hostile preparations which were then being made in the Saracen camp. It seemed to them that it was, humanly speaking, impossible to lose that beloved land, which had been purchased by so many labors, and, as it were, consecrated by an effusion of Christian blood. But towards the close of the year 1144, a fatal disaster disturbed their security and overthrew all their hopes. The city of Edessa, the chief bulwark of Eastern Christendom, fell again into the hands of the Mussulmans. Edessa, according to an ancient tradition, was the first Christian city, for it was said that its king had been converted by Jesus Christ Himself. The fall of Edessa made Antioch tremble, and Jerusalem, at that time governed by a woman, was left desolate and defenseless.* At this perilous juncture, a cry of distress arose from the East which resounded throughout western Christendom. The misfortunes of the Holy Land excited a universal sorrow—but nowhere did they meet with more deep sympathy than in France. The new kingdom had been conquered and founded by the arms of France; French princes were its feudatory possessors; a Frenchman was seated on the throne of Jerusalem; and although every Christian state was interested in the preservation of this eastern colony, on account of the immense resources which it offered for the piety of pilgrims as well as for the purposes of commerce and navigation, yet the honor of France in some sort depended thereon, as that country was more closely allied to the Holy Land, through the French princes who were its rulers. The news of the capture of Edessa reached France about the beginning of the year 1145; and the idea of hastening to the assistance of the eastern Christians forthwith took possession of the mind of Louis VII. The young king, who suffered from an uneasy conscience, hoped that so holy an enterprise would blot out his errors and afford him, at the same time, an opportunity of displaying his valor. The remembrance of his unjust quarrels with the Holy See, the remorse he felt for his exactions in Champagne, and above all, for the horrible catastrophe of Vitry-le-Brule, weighed heavily on his soul; and to these powerful motives was added his desire of fulfilling the vow made by his elder brother, who had died before he was able to accomplish his resolution of making a pilgrimage to the Holy Land.

Notwithstanding these considerations, however, Louis VII did not fulfill his generous intentions; and whether the difficulties of the undertaking appeared to him insurmountable, or whether his ardor was cooled by the remonstrances of his minister, Suger, many months elapsed, during which the sympathy of the country was only expressed by tears and fruitless lamentations. It belonged to the Roman Pontiff, the common father of the Eastern and Western Christians, to give an active impulse to the interest universally excited by the fate of Jerusalem. He turned his eyes towards France, the country of those illustrious heroes, who, forty years before, had delivered the Holy Sepulchre. He exhorted their sons to defend this glorious conquest of their fathers, and he offered the honor of the initiative in the undertaking to Louis VII.* The words of the Holy Pontiff met with a powerful echo in the king's conscience, who now only awaited some solemn occasion to publish his pious intentions.

"In the year of the Incarnate Word 1145, on the feast of the Nativity,'' says the chronicler, "Louis, King of France and Duke of Aquitaine, held his full court at Bourges, to which he more especially summoned the bishops and lords of his kingdom, and confided to them the secret intentions of his heart.

"After him, Godfrey, Bishop of Langres, a man of great piety, spoke, in moving terms, of the destruction of the city of Edessa, and the disgraceful yoke which the infidels had imposed on the Christians. His words, on this sad subject, drew tears from all present; he then invited the assembly of nobles to unite with the king in rendering assistance to their brethren.

"Nevertheless, the bishop's words and the king's example only sowed a seed, the harvest of which was gathered at a later period. It was decided that a larger assembly should be called together at Vézelay, in the country of Nivernais (in Burgundy), at Easter-tide, so that on the very feast of the Lord's Resurrection, all those who were touched by His grace might concur in the exaltation of the Cross of Christ.

"The king, who was very solicitous for the success of his design, sent deputies to Pope Eugenius, to inform him of these matters. The ambassadors were received joyfully and dismissed with apostolic letters, enjoining obedience to the king on all who should engage in the holy war; regulating the fashion of the arms and clothing of the soldiers of the cross; and promising unto those who should bear the sweet yoke of Christ, the remission of their sins, and protection

It was accordingly resolved that a new Crusade should be undertaken; but public opinion was not agreed as to the expediency of so arduous an enterprise. No one had presumed openly to oppose the king's resolution; but the ardor of enthusiasm was dampened by political troubles, and the dangers of such a distant expedition. The spark was still wanting which was to kindle the materials for so vast a conflagration. The state of affairs was no longer the same as at the time of the first Crusade; the ardor of the Knights of the Cross was very much cooled by their knowledge of the places and of the obstacles to be encountered, the remembrance of the sufferings which Godfrey's companions had endured, and the experience of their old warriors. Suger, above all, the prudent counsellor of Louis VII, who entertained a very positive view on political matters, did not approve of the project of the Holy War, and he endeavored, though unsuccessfully, to turn the king's mind from this design. With reason and conscience on his side, he did not hesitate to trust the decision of this matter to the wisdom of the holy Abbot of Clairvaux. The latter was, therefore, summoned to Bourges; and Suger, in submitting this important question to his consideration, was far from supposing that St. Bernard himself would ardently embrace the idea of a Crusade, and renew, throughout Christendom, the wonders of the age of Peter the Hermit.

Bernard, however, refused to pronounce his opinion before the arrival of the apostolic brief. Many historians even say that it was by his advice Louis VII sent ambassadors to Rome. But the private letters which St. Bernard wrote to Eugenius III, on this occasion, afford evidence of his personal views, which he imparted to the Holy See. "The great news of the day," he writes, "cannot be a matter of indifference to anyone; it is a sad and serious affair, and our enemies alone can rejoice at it. That which is the common cause of Christendom ought likewise to be a subject of universal sorrow. . . I have read somewhere that a valiant man finds his courage augmented in proportion as his difficulties increase; and I add, that the just man also grows greater ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Copyright Page

- THE MEMORARE

- CONTENTS

- Preface

- First Period Domestic life of St. Bernard, from his birth till his entrance into the Order of Citeaux. (1091-1113)

- Second Period Monastic Life of St. Bernard, from His Entrance into the Order of Citeaux, to His Political Life, Connected with the Schism of Rome. (1113-1130)

- Third Period Political Life of St. Bernard. (1130-1140)

- Fourth Period Scientific Life of St. Bernard, From His Disputes with the Heretics to the Preaching of the Second Crusade. (1140-1145)

- Fifth Period Apostolic Life of St. Bernard, From the Preaching of the Crusade Until His Death. (1145-1153)