- 306 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Hell and how to avoid it are perennial topics of interest for believing Christians and others. With good reason. Entire libraries have been written on the subject. Most people, even those familiar with his classic, do not realize that Dante Aligheri's Divine Comedy, chock-full as it is of history and politics, is a masterpiece of spiritual writing. The most famous of his three volumes is the Inferno, an account of Dante's journey through the underworld, where he sees the horror of sin firsthand. Join Dante and—guided by Oratorian Father Paul Pearson—with him...

- learn that the sufferings of the souls in hell are the natural consequences of the spiritual disorder of their sinful actions.

- develop a profound hatred for sin, not merely because it offends God, but because it will destroy your soul and thwart your happiness, both on earth and for eternity.

- observe the horrible punishments of the damned and be shocked into a state of enlightened self-interest.

- armed with the knowledge of what sin does to us, resolve to fight against it with all your strength.

- realize that this literary journey through hell is intended to lead you to heaven.

A reading experience like no other, Spiritual Direction from Dante, will educate and entertain you, but most importantly, will help you avoid the inferno!

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Spiritual Direction From Dante by Paul Pearson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Medieval & Early Modern Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

THE INFERNO

CANTO 1

Wandering From the Path

Self-Sabotage in the Spiritual Life

Rejecting Our False Self-Reliance

Learning to Hate Sin

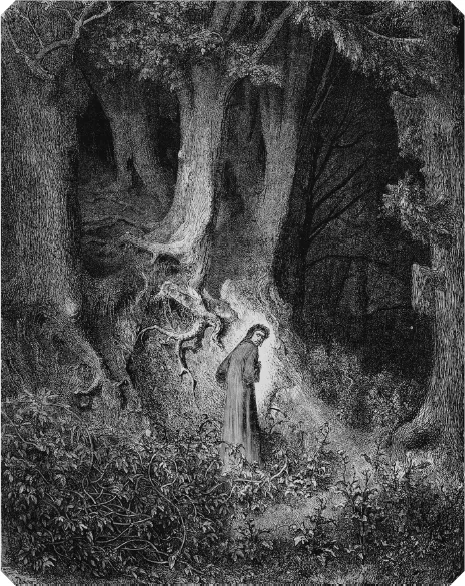

Nothing can expose our vulnerability more vividly than the experience of being lost. Perhaps we have been hiking confidently through the wilderness, secure in our sense of direction, enjoying the splendid scenery, and basking in the beauty of creation. Life is good. A moment comes, however, when an expected landmark is not where we calculated it would be. Nothing seems to indicate the right path. Perhaps we dash around trying to find the path, but our growing sense of panic only makes matters feel more desperate. And since none of our friends or family knows where we are hiking, no one will know where to begin to look for us. We are on our own. The world that moments ago seemed so beautiful and comforting now seems threatening, as though conspiring against us and tracking us down, like a predator out to get us. We are alone and afraid. How did we manage to get off the path? How could we have been so careless? It is our own fault; we know that. But this realization only makes the feeling worse. But this wandering takes on an eternal importance when we have lost the path in our journey to God.

1“Our life …” The opening line draws us into the narrative. Dante intends his account of his own personal struggle against sin to be more than autobiography; it is intended as a sort of parable of the human condition. Although much of what Dante says is highly personal in nature, almost confessional, we are meant to take the journey with him, to learn the lessons that can apply to our own lives. St. Philip Neri would agree wholeheartedly. He had a maxim that his followers recorded after his death: “He who does not go down into hell while he is alive, runs a great risk of going there after he is dead” (15 November). Welcome to that spiritual journey! Enter into it with eyes and ears open, and, even more importantly, with hearts open. This is for you, and, in a real sense, this is about you.

4We often bluster when we are lost, confused, or bewildered. We pretend to know where we are and where we are going, we pretend to be courageous, but we know, in our heart of hearts, that we are indulging in make-believe, whistling in the graveyard. Dante’s reaction to being lost, however, is very straightforward and honest: he is afraid, so afraid that he can hardly bear to remember it.

We might avoid admitting it, but life often brings this sort of fear out in us, especially when we seem to have lost our way. We cover it up as a lack of confidence, or a bad self-concept, but the truth of the matter is that we, too, are afraid. Dante wants us to face the fears we encounter in our lives without the need to retreat to playacting. The “dark wilderness” of our lives (we all have it) is frightening. Let’s not pretend. This fear is really the theme of the first couple of cantos of the Inferno.

10We might know when we discover ourselves to be lost, but just exactly when we became lost is unclear. How we get lost is often difficult to pinpoint because it is the culmination of thousands of little choices, the product of lukewarmness more often than determined evil. There usually isn’t a dramatic moment when we choose decisively to leave the path. We wander more than choose. A little off the path here, a little more there. When did we stop saying those prayers that were once so regular a part of our life? When did that bad habit really become a habit? It is a death by a thousand cuts.

Perhaps that is why Dante’s recognition that he is lost happens only “midway upon the journey of our life.” It takes a while to get ourselves thoroughly off track. The modern world would refer to this as a sort of “mid-life crisis,” a product of innumerable choices that land us in a place we had no intention of entering. We are bewildered: how did we get here? How did it come to this? What happened?

Dante describes himself at the time of his wandering as “so full of sleep.” Perhaps he is referring to the way passion can lead our intellects into a sort of moral slumber, dulling our conscience so that we barely notice when we leave the path. We become so accustomed to the wrongs we do, so weary of fighting, that we come to a place where we really stop noticing that what we are doing is in fact wrong. Conscience has been lulled by the lullaby of the world and our bodily desires, until finally its eyes begin to close.

16We see in a dramatic way the stages we pass through once we recognize that we have lost the way. First, we are afraid and bewildered. Second, and this is where Dante is at the moment, we are convinced that we can cope. Dante experiences hope at the rising of the sun, which he sees as a glimmer of light over the hilltops. He thinks he sees the way out of the dark woods, out of the problems into which his life has descended. How often men talk themselves into thinking that they can solve their problems on their own—never ask for directions! Like Dante, we tell ourselves that we can calm down: it will all be fine. We know just what we need to do to get back on the right path. Misplaced confidence fills our hearts like a reveler making New Year’s resolutions while filled with champagne. We mean them when we say them, and saying them gives us a warm glow inside. How many of our bold resolutions come to nothing almost immediately? Think of the alcoholic swearing off the drink, or the adulterer who says he’ll never be unfaithful to his wife again. They might mean what they say, but what would you predict about their future?

WHEN we recognize that things are going badly and we are wandering off the path, why is it so difficult for us to get back on it? Unfortunately, the answer to that question is not some external force or obstacle; it is something self-generated that arises from within us. In the spiritual life, we are often our own worst enemies. Our good resolutions and carefully designed plans often fail as a result of an act of self-sabotage. The beasts inside us keep us from doing what we so devoutly planned. Saint Paul called it the “old man.” But whatever we call it, we know it lurks inside of us, thwarting our good intentions.

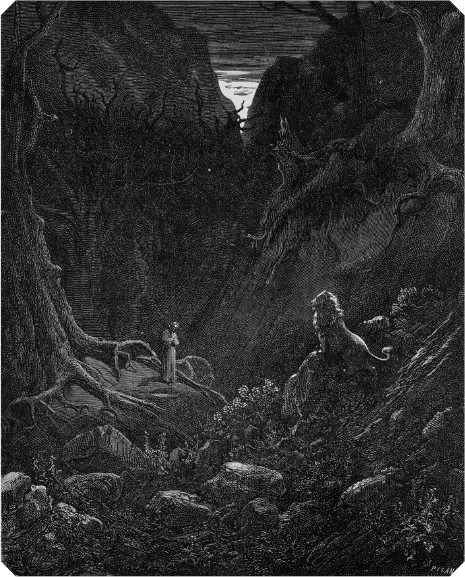

31Dante’s confidence is short-lived. Just “where the steeper rise began,” just when he faces a challenge that will make a real demand on him, he is stopped in his tracks. When Dante begins his ascent up the hill, towards the light, a leopard blocks his way. His best intentions and desires are thwarted by the beast that is a symbol of the vice of lust.

Here we see one of Dante’s important literary devices: his struggles with particular beasts here and his trials in certain circles of hell and terraces of purgatory are a sort of personal revelation. He struggles with those beasts and in those places dedicated to the sins that infect him. Some circles he will breeze through because those sins did not weigh upon his conscience. As a result, Dante’s journey is almost like a very personal examination of conscience, exposing to us the weaknesses in his soul that stand between him and true holiness. The first of these impediments is lust, embodied in the leopard that prevents him from making any progress up the hill.

34No matter how Dante tries to go around the leopard, he can’t. The leopard stalks him, “check[s] me in the path I trod.” Don’t our weaknesses and temptations seem to attack us at the worst possible time? It is easy to feel like prey being stalked by the predator. Getting away from our habitual sins isn’t as easy as it sounds. Those who do not suffer from the habit do not really understand. The habit can leave us feeling helpless, like a small animal held at bay by a crafty hunter.

44Dante’s personal sins are blocking his spiritual progress. Any hope he had of escaping the leopard is dashed when a lion enters the scene as well. The lion is a symbol of pride and perhaps also of the anger that stems from pride. The lion is “hot with wrath” and is coming straight for him. As an exile, Dante is filled with resentment and rage at what he perceives to be grave injustices inflicted by his political foes. We’ll see many instances of Dante’s struggles with these faults.

49The third beast to block Dante’s progress is the she-wolf, emaciated, driven by hunger, both personal and on behalf of her offspring, to do whatever it takes to get her prey. She seems a symbol of greed or avarice, “stuffed with all men’s cravings.” Again, as an exile, Dante would be particularly troubled by the loss of the material goods he left behind and by the desire to reestablish his former standard of living.

THINKING that we can manage on our own, thinking that it is our duty to manage on our own, is an enormous stumbling block in the spiritual life. The path we are trying to follow is supernatural, beyond our abilities. It is foolish pride to insist that we can do it ourselves. Most spiritual writers recognize that a transformation happens in us the moment we realize that we cannot trust our own powers, no matter how painful that experience might be. For some people, especially those who do not acknowledge God, self-distrust can lead to a feeling of despair; we have tried everything, we have done everything in our power, and it has not worked. We have nowhere else to turn. But for the believer, learning to distrust ourselves can open us up to trusting the power of God. We will never learn to receive from him the grace we need so long as we are obsessed with strategizing and coping. But what an uncomfortable bit of self-knowledge it is to see that we cannot depend upon our own powers! This is a sort of knowledge that we must almost always acquire by the painful experience of trying and failing, and trying and failing yet again. It is something we see only when we are face-first in the dirt. We discover that we need help, and that is profoundly humbling.

52Dante’s self-confidence has turned to despair. It is the she-wolf, finally, who so weighs Dante’s spirit down that he gives up hope of reaching the hilltop. Like a gambler who, knowing when to cut his losses, leaves the table, Dante gives up hope and turns back into the dark valley from which he had struggled to escape. This turning back is not necessarily a bad thing. If Dante, recognizing that he cannot make progress on his own, gives up the spiritual journey, that is a disaster, a tragedy. If his self-knowledge leads him to ask for and depend upon God’s strength, this apparent defeat is the first signal of victory. Before we truly trust God, we must have a sincere distrust of our own powers, a distrust founded upon our direct experience of failure. It is a painful lesson to learn, but that does not make it any less necessary.

65Dante sees someone and desperately cries out for help. He does not know who it is and does not really care. He wants someone, anyone. “Mercy upon me, mercy! … whatever you are, a shade, or man in truth!” His cry is an admission of his own inability to climb the hill and escape the dark wilderness. The person he sees turns out to be Virgil, Dante’s role model as a poet, come back from the dead. Virgil only gradually reveals himself to Dante, one clue at a time.

76Virgil knows perfectly well why Dante turns back and does not climb the hill—that’s why Virgil’s been sent. He asks Dante so that he’ll be forced to put it into words, to admit out loud his helplessness, in much the same way that we must put our sins into words in the sacrament of confession, even though God knows perfectly well what we have done before we tell him. Saying the words, admitting it to ourselves and to someone else, really does matter.

79The fact that Dante’s guide is Virgil is both a blessing and a curse. Obviously, Virgil is someone Dante can trust unreservedly. But, at the same time, being on this path with Virgil requires that Dante reveal his failings to the very man he respects most. Dante is forced to humble himself before his hero, the very person with whom he would most want to make a good impression. It is not surprising that his “forehead [was] full of shame.”

88Dante is honest with Virgil and indicates the beast that made him turn away from his ascent. He humbly asks for help: “Save me from her.” There comes a time when we get so caught up in sinful habits that we don’t have the ability to help ourselves, when the help has to come from the outside, like someone so sick that he can’t get the medicine that will cure him.

WHAT motivates us to accept the help offered to us and to fight to get back on the pathway to heaven? Often pious thoughts about obeying God’s commandments or contemplating the wonders of heaven are not enough, not nearly enough. The battle is too difficult to be fought with such delicate weapons. We need a more deeply human, more visceral motivation, something that goes as deep as our attachment to sin. What we need to develop is a sort of gut reaction to the destructive power of sin. We need to feel revulsion for what it does to us. For this reaction to become operative in our soul, we need to see sin as it truly is, in all its ugliness.

91Virgil indicates that Dante can’t merely walk up the hill; that just will not work. “It is another journey you must take … if you wish to escape this savage place.” Sometimes good strategies and intentions aren’t enough. Something more is needed. Being serious about fighting sin, especially habitual sin, requires developing a hatred of the sin and its destructive power. We need to strip away the alluring disguise sin wears and reveal the disorder, the ugliness, and the misery it causes. On his journey, Dante will need to see...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- The Inferno