- 250 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

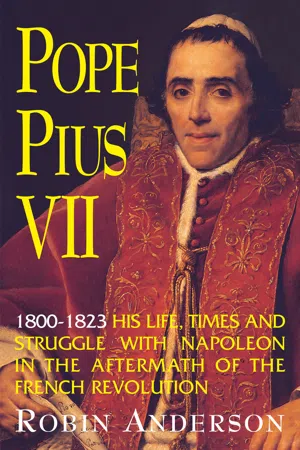

The French Revolution had wrought religious and civil havoc in France and the Italian states. Thousands of French priests had been killed or deported; other priests and bishops were forming a schismatic national Church; the previous Pope had been kidnapped and had died in exile. Catholics were losing the Faith and adopting an attitude of resistance to all authority..This was the beginning of the reign of Pope Pius VII (1800-1823)-one of the most difficult and confusing eras in Catholic history.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Pope Pius VII by Robin Anderson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Christian Denominations. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Theology & ReligionSubtopic

Christian Denominations~ 1 ~

EARLY YEARS

Benedictine Monk—Professor of Theology Abbot—Bishop of Tivoli

Barnabas Chiaramonti was born on the eve of the Feast of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary, 1742, in Cesena, not far from Bologna. The reigning Pope was Benedict XIV. His grandfather, Count Scipione Chiaramonti, related to the Clermonts of France, was a well-known mathematician and philosopher, friend of Galileo and fellow of several European universities, including Paris and Oxford. He became a priest late in life and founded the Oratorians of St. Philip Neri in Cesena.

Barnabas' father died when he was eight years old. His mother, the Marchioness Giovanna Ghini, brought up her five children—two sons older than he, one younger and a younger sister—strictly and piously. When he was 12, she entrusted him to the Benedictines of Mount St. Mary's Abbey just outside Cesena and is said to have foretold that he would become pope. She herself later retired to the Carmelite convent at Fano, where she died in 1777, after 15 years of exemplary religious life.

Not much is known of the boy Barnabas' early training. He was high-spirited, high-strung and not at first able to adapt himself to monastic discipline. He tried to set fire to his mattress in protest for being severely punished and rode a donkey up the main stairway to the upper story of the abbey, causing consternation among the monks resting in their cells.

Soon, though, he settled down and submitted to the Benedictine Rule under the gentle but firm guidance of his novice-master and experienced educators. After two year's trial, he was allowed to take the religious habit, with the name of Gregory, and was professed two years later in 1758.

Three years of studying for the priesthood at St. Paul's Abbey, Rome, culminated in a successful public debate before his being sent after ordination in 1761 to pursue philosophical studies at St. Justa's Abbey, Padua. St. Justa's had been a famed center of true reform and learning. The rule was well kept, with accompanying works of charity, but poverty imperfectly observed. Personal allowances were received from relatives for extras such as books, journeys and food to supplement the fare served in the refectory. Fr. Gregory's family had been obliged to move from their ancestral mansion to a smaller residence, and the little they could send him went mostly for books that formed the beginning of his private library.

A few years before his arrival, the germs of Jansenism had entered St. Justa's Abbey. The Venetian Inquisition discovered meetings held by a French Dominican in one of the monk's cells. There was no condemnation as the culprits had been careful to avoid any explicitly heretical opinions, but the damage was done. The false teaching spread to others of the community, and before long Venice itself was affected and infected. Material and political interests soon began to predominate over spiritual ones.

It was something of a miracle of grace that at this stage the future Pope remained immune from unorthodox tendencies and did not himself absorb the Jansenist views of some of his teachers, who looked askance at Rome and were hostile to the Jesuits. His experience at St. Justa's certainly afforded him first-hand knowledge of the Jansenist mentality, as well as its protean tactics of disguising itself and changing to suit all places and circumstances.

Fr. Gregory—or Dom Gregory, in the Italian usage—was recalled to Rome in 1763 in order to complete his theological formation with a view to professorship at St. Anselm's College (at that time under the wing of St. Paul's Abbey), founded expressly to counteract Jansenist ideas that were penetrating Rome and religious life there.

Then from 1766 to 1775, Dom Gregory was professor of theology at St. John the Evangelist's College, Parma. Here he gained direct experience in what was practically a small-scale pre-experiment of the French Revolution. Voltaire was played in the theaters; the works of Locke, Hume, Rousseau and the French "philosophes," sold in all the shops, were read and discussed in private and public.

Dom Gregory made full use of Parma's Palatine Library, one of the largest and most up-to-date of Italy. He was librarian of St. John's Abbey and caused eyebrows to be raised by altering the motto Initium salutis sapientia et scientia ("Wisdom and learning are the beginning of salvation") to Initium salutis scientia et sapientia ("Learning and wisdom are the beginning of salvation"). He felt this reversal of the last words was more in keeping with an age avid for learning. It also denoted his own teaching program. Putting learning before wisdom would not seem quite consonant with the Augustinian dictum and Anselmian philosophical principle, "Believe in order to understand," that he was later to profess and teach in Rome; yet if learning be truly grounded on moral norms, wisdom may certainly follow.

Dom Gregory's personal library included the complete works of St. Augustine, St. Basil, St. Athanasius, St. Gregory the Great, St. Jerome, St. Hilary and Lactantius. He had the works of other Fathers of the Church in critical editions brought out by the French Benedictine Maurists (founded in 1618 by St. Maur). The copy he acquired of the Dictionnaire raisonné des Sciences, des Arts et des Métiers by Diderot and his French "philosophes" collaborators (put on the Index of Forbidden Books by Clement XIII) was only for the Abbey library, which he felt ought to contain so famous a contemporary work whose shafts against faith and Christian morality, slipped into informative articles of considerable utility and interest, did much in disposing people's minds for revolution.

The young theological professor of St. John's, Parma, kept abreast of the times and must also have studied the famous work of the Abbé Condillac,1 adopting what was good in his new psychological methods. But he distinguished between these and his faulty philosophical system that suppressed reflection in favor of ideas, all coming, according to Condillac, from experience or external sensations, the human mind being only a sort of mosaic.

Modernization of the little Duchy of Parma was carried out according to the physiocratic theory of "government by natural order" putting the cart before the horse, giving primacy to economy. Despite Pope Clement XIII's condemnation, reforms ill-suited to local conditions were hurried through. Writings from abroad (meaning Rome) were forbidden, the Jesuits expelled (before the general suppression) and foreign priests and religious banished. The people were assured that nothing was being changed essentially—only abuses being eliminated. The real defenders of Catholicism were "the friends of truth" (one title given by the Jansenists to themselves) and the "enlightened" governors of Parma—not the Pope, his medieval court and Roman immobilism.

The result was a short-lived disaster.

Upon the death of Clement XIV and accession of Pius VI, Dom Gregory was again called back to Rome and appointed to the highest teaching chair of his congregation, that of professor of theology at St. Anselm's. The College, founded in 1687 and opened by Innocent XI, aimed at remedying intellectual decadence in Benedictine monasticism, as well as counteracting Jansenism by the teaching of Anselmian philosophy.2

The loss of the archives taken in Napoleonic times to Paris leaves no data concerning the life of Dom Gregory Chiaramonti at this period. But known results of his professorship reflect the worth of the teacher: many of his students became, in turn, holders of highest university chairs or renowned for their lectures and writings.

Dom Gregory's great personal and intellectual gifts and outstanding success made him a sign of contradiction among some of his brethren. Besides this, he disapproved of the harsh punishments given by superiors for offenders against the Rule. The latter often came to him for help and consolation, and he was accused of inciting insubordination. He defended himself by quoting St. Bernard's maxim that a superior ought to be more loved than feared.

The matter came to the attention of Pius VI, and Dom Gregory was asked to explain himself. Hearing what he had to say so increased the Pope's already existing esteem that he made him an honorary abbot—having the title but not the government—of Mount St. Mary's, Cesena.

But here the same contradictions continued—what is known as persecution of the good by the good. Pius VI, on his way to Vienna in 1782, paid a personal visit to Mount St. Mary's. It was summer, and the Pope found his protégé's cell extraordinarily hot. He remarked on this and was told it was because the kitchen chimney passed through one of the walls.

The Pope went to see the Abbot, found him occupying a cool and spacious apartment and ordered him to change places with Dom Gregory, recalling the monastic duty of perfect mutual charity. But returning to Rome from Vienna in 1783, the Pope put an end to any further unpleasantness by withdrawing Dom Gregory from monastic life and appointing him Bishop of Tivoli.

The monks of St. Paul's Abbey, as well as Cesena, proffered their apologies to the newly elected Bishop, admitted they had been wrong and, in true Benedictine spirit, tried to make up for the past. Bishop Gregory had only words of forgiveness, charity and peace for all.

The new Bishop's ancient aristocratic family background assured him the most respectful welcome from clergy, city governors and people of all classes who still respected time-honored traditional standards. They were astonished to see their pastor as simple and cordial as he was distinguished and cultured and were moved to admiration by his being at all times available.

Bishop Chiaramonti's time was passed in prayer, spiritual exercises, diocesan business and pastoral visitations. He lived with utmost simplicity and frugality, as was always his custom. No archives of his bishopric are still in existence, but details are available concerning his inspection of churches in which he personally ordered redecoration and repairs in minutest detail: walls to be white-washed, tiles of roofs and floors to be replaced, vestments mended, windows cleaned, candlesticks cleaned and polished, missals renewed and worn missal-markers changed for new ones. He took away the benefice of a chaplain whose altar was in a state of neglect until the chaplain had carried out restoration work.

The new Bishop visited his diocese three times in one and a half years. He had to go to some parishes on foot, others on horseback or riding a mule where there was only a rocky and steep track.

Bishop Chiaramonti, for all his mildness and gentleness, showed absolute firmness, even righteous anger, where his episcopal rights were concerned.

Soon after he took possession of his diocese, a picture of Pope Clement XIV (who had suppressed the Jesuit Order) with a halo around his head had appeared posted on the cathedral wall. (The new Bishop was aware that his predecessor had avoided publishing the papal bull suppressing the Jesuits by temporarily retiring and leaving his vicar general to read it. This had scandalized the local Jansenists, loud in their defense of papal authority—in this particular case.) The picture of Clement XIV had appeared without the Bishop's knowledge or permission, was implicitly pro-Jansenist and explicitly anticipated the canonical judgment of the Church with regard to the sanctity of this Pope. Bishop Chiaramonti therefore had the picture removed, but he found that reproductions were being distributed for sale with permission of the Dominican Holy Office official in Tivoli, an ardent advocate of the cause of Clement XIV.

The official refused to withdraw the pictures, and Bishop Chiaramonti was obliged to insist on recognition of his rights as local Ordinary, under threat of ecclesiastical sanctions.

Meanwhile the Bishop became aware that the Dominican official in Tivoli was being underhandedly supported by a colleague holding a key post in Rome in the papal administration. He also suspected that the whole affair had been started by the Jansenists. They still had their spies everywhere, probably knew of his former anti-Jesuitical teachers and now wanted to provoke him, as Bishop, into taking an open stand.

This conviction grew as the Tivoli official, with the backing of the Roman one, continued to resist and defy the authority of Bishop Chiaramonti. The only thing to do was to lay the matter directly before Pius VI—which he did, humbly offering, if justice were not done and his juridical rights not respected, to resign.

The Pope pronounced Bishop Chiaramonti fully in the right and ordered the matter settled accordingly.

The incident is told in considerably more detail by the great papal historian von Pastor,3 naming all persons concerned, which would not be within the compass of this work.

Pius VI several times invited Bishop Chiaramonti to stay in Rome at the Quirinal Palace. But much as he revered and was grateful to the Pope who had so benefited him, he did not feel at ease in the grand life of the papal court. Personal letters of his reveal how much his simple and frank nature disliked the petty calculations of the "clerical labyrinth," as he called it.

The Pope was informed of the Bishop's constant zeal and good works; Bishop Chiaramonti was loved by the people whom he governed, and he taught and sanctified with rare intelligence and fatherly goodness. In 1785, Pius VI created him cardinal and appointed him to the vacant bishopric of Imola.

When he took leave of the clergy and people of Tivoli, after only a year and a half as their Bishop, many wept to lose him, and some predicted he would become Pope.

Chiaramonti waited in Rome for a while at St. Paul's Abbey, where he wrote his first pastoral letter to the clergy and people of his new diocese. Directly and frankly, avoiding the formal style in vogue with many bishops of the time, he asked the secular clergy in particular to preach less by words than by example, warned them against the false worldly spirit of the times and told them that if any committing faults paid no heed to his fatherly correction, he would show himself to be a severe judge and spare no effort in seeing that the prescriptions laid down by the Council of Trent regarding the clergy be exactly enforced.

NOTES

1.Etienne de Condillac (1715-1780), a priest who never exercised his priestly powers, tutor of Louis XV, friend of Rousseau and disciple of Locke. The Italian translation of his Origins of Human Knowledge was dedicated, with critical introduction, to Chiaramonti when he became Bishop of Tivoli.

2.St. Anselm, Archbishop of Canterbury (1033-1109), followed St. Augustine's dictum Crede ut intelligas—"Believe in order to understand." Faith, obtained from Christ and His Church, is the source of all knowledge leading to infallible truth. The moral and reasoning effort needed for possession of truth through mastery of Anselmian philosophy was considered the most efficacious means for rectifying the warped pseudo-Augustinian teachings of Jansenism's originator, Bishop Jansenius of Ypres (1585-1638), which, among other errors (and purporting to remedy ecclesiastical laxity) gave undue regard to political and temporal matters at the expense of spiritual and supernatural ones.

3.Ludwig von Pastor, History of the Popes, vols. 39 and 40.

~ 2 ~

CARDINAL CHIARAMONTI OF IMOLA

The Future Pontiff Faces the Revolution

Dom Gregory Chiaramonti is recorded as having assumed the cardinalate with such outward indifference as to seem unreal. Nonetheless, the monks of St. Paul's fêted their newly created cardinal in grand style on the day of his taking possession of his titular Roman Church of S...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- CONTENTS

- PROLOGUE

- 1. EARLY YEARS

- 2. CARDINAL CHIARAMONTI OF IMOLA

- 3. THE CONCLAVE OF 1800

- 4. THE NEW POPE AND NAPOLEON

- 5. THE POPE IN PARIS

- 6. THE DEEPENING CONFLICT

- 7. CAPTIVITY IN SAVONA

- 8. FURTHER STRUGGLES OVER CANONICAL INSTITUTION OF BISHOPS

- 9. THE CONCILIAR DELEGATION TO SAVONA

- 10. THE POPE AT FONTAINEBLEAU

- 11. RETURN TO ROME

- 12. AFTERMATH

- 13. RESTORATION

- 14. FURTHER RESTORATION, RESTITUTION AND REBUILDING

- 15. THE END OF A TWENTY-THREE-YEAR REIGN

- PRINCIPAL DATES IN THE LIFE OF POPE PIUS

- BIBLIOGRAPHICAL NOTES AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY