![]()

Chapter 1

FINDING THE WAY

IT was the 30th of July, 1915; the second year of the war.

For one four-year-old girl, this was “the Day of the Lord, great and exceedingly bitter.”

Is it possible to speak of a great and bitter day in the life of a child of four? It is certainly not usual, but this book is about a child who was not usual.

On that July morning Anne awoke to see her mother standing by the bed, and her mother’s eyes were red from a night of tears. Three times in this one year of war the child’s father had returned wounded—now, “Daddy is dead.” And the sword went down into the little one’s soul “even unto the division of the spirit.” This is the absolute truth. It was a dividing point. Behind lay an ordinary childhood, full of promise but stained by many faults. After it came the maturity of holiness.

There are several ways of climbing the mountain of sanctity. Anne’s way was to attempt the face of the cliff. She went straight up, for her time was short. God called her to come up the quickest way, and she came.

* * *

Who was this child? Her family called her Nenette, but she had a good supply of other names besides. Jeanne, Marie, Josephine, Anne, all these had been lavished on the eldest daughter of Jacques, Count de Guigné and his wife, Antoinette de Charette.

Anne’s birth on April 25, 1911, was followed a year later by that of the son and heir, Jacques or Jojo; and then came two little sisters, Madeleine and Marie Antoinette, whose long names soon became shortened to Leleine and Marinette.

Their home was the stately Chateau de la Cour overlooking the Lake of Annecy. “We have as fine a chateau as anyone,” Anne once remarked in a moment of weakness. Certainly it was a home worth loving and a little girl might perhaps be forgiven for boasting of it. That part of Savoy is lovely beyond description, and the chateau stands on a height with all the beauty of the lake spread out below.

This was Anne’s home and here she lived all her life except for a few months each winter when the family went to their house in Cannes.

Some Saints’ biographers gravely assure us that they “showed every sign of sanctity from earliest infancy”! Anne can hardly be said to have done that. In many ways she was a dear child, very loving, intelligent and perfectly frank, but also a most tempestuous little person with an iron will when there was question of getting her own way. She may in fact be said to have shown every sign of naughtiness from earliest infancy!

A doctor can testify that there were no signs of precocious sanctity to be seen in the very troublesome baby he had to deal with. The child was sufficiently ill to cause anxiety and it was imperative to examine her. But Anne did not like the doctor, or perhaps his instruments frightened her. In any case she immediately became a miniature windmill with her arms and legs very busy all at once, and when the doctor tried to hold them: “Take your hat and go!” came the furious command from the crib. The little lady could hardly speak plainly yet, but she knew how to make herself understood. Such scenes were not at all unusual.

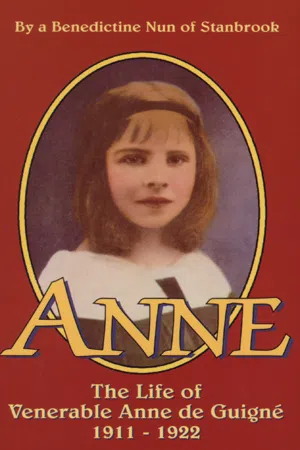

There is a photograph taken when she was about three years old which gives a good idea of her character at this time. Eyes, mouth and chin, all are very hard. There is frankness in the little face and courage, great courage, and the power of great love; but self-will is clearly written there. It is the face of one who will follow none but herself.

Anne was in fact a born leader, but during these first four years of her life she was also a little tyrant. Among other children she not only led but drove. Ordinarily, they were usually glad enough to follow, for there was something very attractive about her and she was full of invention and enterprise; but if anybody showed resistance, there was trouble. The tyrant instinct rose, and she carried all before her, even physically sometimes if she had strength enough!

One summer when she was only three years old, Anne was playing with a boy cousin a little older than herself. After some time they came across a large heap of sand. “Let’s climb on top,” suggested the little girl, suiting the action to the word, but the boy held back.

“No, I won’t,” he said, “it’s too high.”

“But I say you must,” retorted his little cousin. “You shall come up, I’ll make you!” and she began to pull and tug. It was a fine fight, but the little girl was winning when their nurse arrived on the scene and separated the pair. Anne could not have won by strength of arm, but her violence frightened the bigger child. It was a battle of wills. Surely she too had trembled at the thought of balancing on top of that heap of crumbling sand which seemed so high to a three-year-old, but if Anne meant to do a thing, fear would never stop her.

About the same time, she and her cousins were taken to see a menagerie. Anne was younger than any of the others, but as usual she took command of the group. “Come along,” her aunt heard her say to one considerably larger than herself, “I’ll lift you up to pat the giraffe!” She was quite serious about it.

All these things showed that there was a power in the child; but how would she use it? Her mother wondered and prayed and “kept all these words in her heart.”

Anne’s heart was the best part of her. She was really wonderfully loving. But here again there was a shadow to the picture, for she was also jealous. She did not love the brother who had succeeded her in the cradle. She wanted the whole of her mother’s attention; her father’s, too, of course, but particularly her mother’s, and now a new baby was sitting on Mother’s lap. It was certainly very hard, unbearable in fact, so Anne came up one day with a handful of sand which she began to rub into the baby’s eyes. It was not fun, very far from it. She wanted to make Jacques cry because her mother had kissed him.

Fortunately this did not last long, for like most children Anne soon found that a real live baby is much nicer than a doll, and the little sisters who followed had a much better welcome. She began to find it rather pleasant to be the eldest.

She was nearly four when the youngest was born, and she immediately appropriated the new baby as her own property. Marinette had chosen to arrive on the 4th of January in the midst of an unusually severe spell of cold weather, so the bishop gave leave for the little one to be baptized in the house. It was a great day for Anne; she felt she had “come of age,” in fact, for her mother decided that she should be allowed to stand as godmother. Feeling full of importance she made the responses very gravely; but what most impressed her was the fact that she was now responsible for Marinette’s welfare. This was very much to Anne’s taste, and she did not stop to distinguish between spiritual and temporal care! No one in the house had a chance of forgetting that the baby had a godmother. All that day Anne hovered about, trying to get hold of her spiritual charge, and at last succeeded in reaching the crib when the nurse was not looking. But good nurses have eyes in the backs of their heads, and this one looked around in time to catch the godmother just as she was getting the baby into her arms.

“My darling, you mustn’t touch her. Little girls can’t look after babies!”

Anne drew herself up with dignity: “They can on a Baptism day,” she retorted. “I’m her godmother.”

But the nurse was obdurate and the crestfallen little godmother had to retire, vanquished for once.

It had been a happy day for Anne, but her mother was sad, for it was 1915 and the Count de Guigné was not there to see his new little daughter.

At the first outbreak of war, he had rejoined his old regiment, the Chasseurs Alpins, from which he had retired at his marriage for family reasons. He was still quite young, and by 1914 his life was a very busy one, for he had thrown himself into most things that were worth doing, especially the Catholic activities of the district. He was interested in many branches of study too; he lectured, he wrote, and what is not quite so common, he thought deeply and he prayed.

It was a happy life, congenial and full, not easy therefore to leave, but Jacques de Guigné laid it down at the first call of duty and left for the front.

The little family was not long alone. In a month their father was home again, wounded. It was not a very severe injury, however, and before long he was able to get around a little with the help of crutches. Anne took her wounded father very seriously. She quite understood that Daddy had come home to be looked after, and looking after people was very much in her line, so she made up her mind to be his nurse. There were usually too many grown up people around for her to have a chance of doing much, but every now and then she found him alone and could play “nurse” to her heart’s content. She trotted around full of importance, fetching him books and arranging his cushions. Sometimes she was even seen staggering along with his big crutches, though they were about twice as long as herself. The other children were really too small to understand much, so here at least Anne had the field to herself.

Very soon, however, Lieut. de Guigné went back to his regiment, only to return a few days later wounded more severely. This time he might legitimately have taken a fairly long leave, but he felt his duty was with his men and insisted on hurrying back with his wounds still open. In February he was wounded again, so seriously that he was sent to the hospital at Lyons for an operation. Here Madame de Guigné went to see him, taking Anne with her.

It was a strange experience for the tiny child. She stood gazing at the long line of white beds, strangely awed by the sense of suffering all around. There was no playing at nurse here. Her mother told her that all these poor men were suffering for France—her father, too. It was a great thought. Dimly she began to realize what life was about.

But Anne’s father was a brave and strong man. He got the better of his wounds again, and on the 3rd of May, feast of the Holy Cross, he said goodbye to his home for the last time and went back to the horrors he knew too well.

This time God asked for the supreme sacrifice. The Count de Guigné was ready. With a smile on his lips to the priest who had given him absolution, he led his men to the attack and fell, mortally wounded at last.

The news reached the poor widow four days later on July 28. That night she grieved alone while the little orphans slept, but next morning she rose and went to her eldest child.

Of St. Thérèse of Lisieux it is said that the sun shone on her joy and the rain came with her tears, but it was not so for Anne. The glory of a perfect summer’s day shone upon her grief. Was it the irony of nature? At the time it may have seemed so, but the Lord of nature knew that this day her glory had begun, for the light of grace poured in through her open wound and lit up the child’s life. It was right that the sun should shine.

Anne was no longer the same. She looked long and thoughtfully at her mother’s sad eyes. How much did she understand? Who can say? A little child’s mind is hard to read. But she knew that in dying we pass out of this world to God. Did she know that we can “die powerfully”? Probably not; but we know it, for even the blind and “slow of heart” can hardly fail to see that the father’s willing sacrifice drew down a flood of grace on his little daughter. From the day of his death it seemed as if all his virtues had fallen to her as an inheritance, and we know too that she worked with the gift of God till it brought forth the hundredfold; but in this world the mysteries of grace can be seen only dimly, “in a dark manner.” The full story is written in the Book of Life.

Anne was a practical little soul. She realized now that to reach God we must please Him and to please Him we must be good and that the surest way for a little girl to be good is by pleasing her mother. So she set to work first of all to comfort her mother in every way she could. All day long she tried to be thoughtful and to remember the things she had been told to do—and tried to make the others remember too, for the old instinct of command was not dead! If she herself had started on the way of perfection, she meant to carry them all along with her.

“You must be good, Jojo, because Mother is sad,” she used to whisper to her noisy little brother, who was more inclined to listen now that there were no more tempers to be feared from Nenette. The children were too young to realize that there was a change in their sister, but they began to love her more and turned to her for everything. “Anne always knows how to arrange things,” Jojo would say; and she did, but now it was usually at her own expense. All she thought of was how to please the others, so of course there were no more tempers nor selfishness, because she no longer wanted to get her own way but to make them happy, and above all to keep them good. But this was hard work for the poor little girl, though scarcely anyone guessed it.

The new governess who arrived in January 1916 certainly never suspected anything of the kind. She was in fact very much astonished to learn from Madame de Guigné that the elder little girl, who had struck her as being such an exceptionally sweet, gentle child, had been most troublesome and difficult to manage only a few months before.

“I first took charge of Anne when she was four and a half years of age,” writes Mlle. B., “and I was really charmed by the easy grace of her manner as she came to greet me. One could not help loving her. Although so tiny, there was something about her even then that inspired respect. She was very sensible too, and she had such a kind little heart. . . . When we returned to the Chateau at Annecy, she was very anxious about me for fear I should fret over leaving my parents who lived near Cannes. Almost as soon as we arrived, she took me around the garden and wanted me to pick some flowers. ‘You must do just as if this was your own home,’ she said; ‘pick all the flowers you like and send them to your mother to comfort her.’ The next morning I heard a soft little knock at my door. It was the dear child coming to see if I had slept well! All day long she was trying to help me. . . . and when we went for a walk she would let the others go with their mother while she took my hand, for fear, as she said, that ‘Demoise might feel left out.’ Anne was always so sweet and unselfish.” Rather different from the little lady who would not have anyone else sit on her mother’s lap!

“Demoise” was the quaint name Anne had invented for the governess. And why? The reason is illuminating: “I’m going to call her that,” she explained, “because ‘Mademoiselle’ sounds so stiff, and we want to make her feel at home.” There was always a wonderful delicacy in her courtesy.

Of course Anne came of a great race. Madame de Guigné traces her descent not only from St. Louis of France, “the perfect knight,” but also from General de Charette, who fought for the Pope with the Pontifical Zouaves. After the Italian campaign, the Frenchmen returned to support their own country in the Franco-Prussian war. It was then, during the retreat of the French troops at the battle of Patay, that de Charette raised the banner of the Sacred Heart and led his heroic little band, three hundred strong, against two thousand Prussians.

But in Anne there was more than the courtesy of kings or a soldier’s courage. She had that which made St. Louis a perfect knight: the charity of God which “is patient. . . . that dealeth not perversely, seeketh not her own. . . . beareth all things, hopeth all things, endureth all things.”

![]()

Chapter 2

THE GREAT MEETING

AS EARLY as June 1915, when she was only four and a half, Anne had spoken of her First Communion. She had always loved Our Lord, though at first, like most of us, she loved herself as well; but since the great day when she turned her whole heart to God, the desire to possess Him in Holy Communion became stronger and stronger.

That autumn, when the family went to their house in Cannes for the winter, her mother thought Anne was old enough to join the catechism class at the Auxiliatrice convent. This was an immense joy to the little one, for she felt she was now preparing for the great event in real earnest, though she knew she was a good ...