![]()

PART I:

THE HISTORICAL RISE OF PHILOSOPHY

![]()

The First Beginnings of Philosophy

Let us call to our aid those who have attacked the investigation of being and philosophized about reality before us.

ARISTOTLE, METAPHYSICS, I, 3.

The Philosophers of Nature

The first philosopher on record is a man called Thales. Thales lived at the beginning of the sixth century B.C., at Miletus, a Greek colony on the coast of Asia Minor. He was one of the legendary Seven Wise Men of Ancient Greece and knew the famed lore of the Chaldeans. The Chaldeans had centuries-long records of the movements of the heavenly bodies, and they used this information to cast horoscopes. Thales and other early Greek philosophers, however, instead of trying to tell fortunes by the position of the planets, used this knowledge of the heavens to try to explain rationally the nature of the heavenly bodies themselves and their movements.

This at once marks off the early Greek philosophers from the other wise men of antiquity. The Greeks endeavored to find explanations for natural phenomena which did not bring in magic or the activity of the gods, not because they were necessarily atheists or had no use for religion, but because they recognized that magical, religious, allegorical, or mythical explanations differed from a rational, scientific explanation.

Beyond this universal concern of the first philosophers to explain the nature of the heavens by reason alone, they desired also to find out what everything comes from. Thales said everything comes from water. Another thinker, Anaximenes, said air is the source of everything. Still another, Heraclitus, said fire; and another, Empedocles, suggested the four elements—earth, air, fire, and water. These answers may appear naïve at first sight, but they are more profound than they seem. Thales and the other early philosophers were not unaware of the variety and multitude of things. What they were really trying to get at was the connection of things, the interrelations between them. Their question really is, “What do all things have in common?” for it seemed to them that, behind the vast multiplicity of things that make up the universe, there is some principle of unity, the very insight that is embodied in our word universe, which means “combined into one.”

These early philosophers were called cosmogonists, because they tried to discover the matter of which the cosmos is made up. They are also called philosophers of nature because their interest was directed mainly to the external world. Still another name given to them is the term hylozoist, which comes from two Greek words meaning “living matter.” They held that the stuff from which everything comes is alive. The world, in other words, is like a great animal, or a human being enormously magnified. “Just as our soul, being air, holds us together, so do breath and air surround the whole universe.”1

A final label attached to these first philosophers is the term sensist. This means that they take into account only what falls under our senses. Only the things we can see and touch and otherwise sense are real. Unlike later sensists, these early philosophers did not deny the existence of intellect. They simply did not know about it. However, Pythagoras, the next pioneer we are going to study, took for his field of investigation the mysterious realm of numbers. His speculations were to suggest that there is more to the reality of things than their surface appearance, and that the senses are not of themselves sufficient to account for everything we know.

Pythagoras and the Philosophy of Number

Pythagoras (572-497 B.C.)2 was born at Samos, an island off the coast of Asia Minor, and came in contact there with the Milesian philosophers. To evade the rule of a political tyrant, Pythagoras emigrated from his homeland to Croton, in southern Italy, where he founded along religious lines a community of men dedicated to a life of scholarship and good works. They stressed philosophy as a way of life rather than a body of doctrine, a tradition continued later on by Socrates and Plato.

The greatest achievements of the Pythagoreans were in the realm of mathematics and they made important discoveries in the field of arithmetic and geometry. At this period the Greeks used the letters of the alphabet to designate numbers. Pythagoras used dots instead of letters, the dots being a kind of substitute for the pebbles with which the first counting was apparently done. This usage is not original with Pythagoras, for it had been anticipated by the gamblers of antiquity who used dots to mark the numbers on dice.

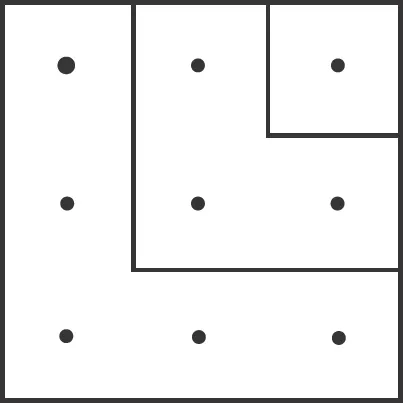

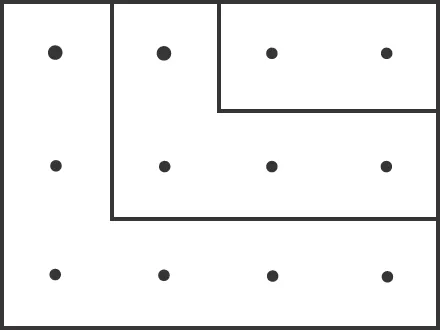

Pythagoras discovered that numbers could be fitted into regular patterns. The series of whole numbers, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, etc., were made up of triangular numbers, thus:

The series of odd numbers fitted into square patterns (we still speak of “square” roots):

Even numbers make up oblong figures:

These numbers are called “figurate,” from the Greek word eidos which means “pattern” or “figure.” When today we say we are “figuring out” the answer, or when we refer to a column of “figures,” we are reflecting the persistence through the long centuries of this ancient Pythagorean concept.

The Pythagoreans elaborated many of the theorems which were later gathered and systematized by Euclid. Among them is the important theorem which states that the square on the hypotenuse of a right-angled triangle is equal to the sum of the squares on the other two sides. This is still called the Pythagorean theorem, and Pythagoras is said to have sacrificed an ox to celebrate his great discovery.

Out of the Pythagorean interest in mathematics and music grew the conviction that reality itself consists of numbers. Everything we can see and touch is made up of numbers. Number therefore is more basic than water or fire or any other of the physical aspects of things. Numerical proportion and harmony account for the order and arrangement of things in their various forms.

The Pythagoreans3 taught the doctrine of the transmigration of souls—the passage of the soul, that is, from one animal body to another. (An early poem makes fun of Pythagoras with the story that he stopped someone from beating a dog, saying that he recognized in the dog’s anguished yelping the voice of a departed friend.) The only way the soul could be freed from its captivity within the body was by a process of self-discipline and purification. It was the task of the Pythagorean Brotherhood to bring about this liberation. Besides mathematics, they specialized in the study of music and medicine, and we are told that they purged the body by medicine and the soul with music.

A favorite comparison of the Pythagoreans was that which likened the body to a musical instrument, with the bodily contraries of hot and cold, wet and dry, corresponding to high and low pitch in music. The healthy body was one in which the various elements were properly blended just as the sounds given out by the strings of the lyre must be properly blended to produce music. And just as we speak of an instrument being in tune, so too we speak of body tone. The metaphor survives to this day when we say we need a spring tonic, that our system is out of tune, that we are under too much tension and need relaxation, or contrariwise, that we are all unstrung.

The Pythagorean strain, with its emphasis on the mysterious properties of numbers and the unsuspected harmonies within nature, was to be of the highest importance in the later development of Greek philosophy. The Brotherhood itself, however, came to an untimely end. They had in the course of time gained political control of Croton and other places in southern Italy. The inhabitants eventually rebelled against their rule because of an attempt, according to one tradition, to impose the dietary restrictions of the sect—including the prohibition of beans—on the population at large. The semi-monastic centers of the Brotherhood were destroyed and the few survivors scattered.

![]()

The Problem of Change and Permanence

The One remains, the many change and pass.

SHELLEY, ADONAIS.

One of the most striking and mysterious of all the appearances in the world about us is that of change. The problem early arose as to how things can change and yet remain themselves, be infinitely diverse and yet stem from a single or a few basic elements. This is what is known as the problem of change and permanence, and it was destined to dominate Greek philosophy for a century and a half. The philosophers we are now going to study set the ultimate extremes for all time in the explaining of change and permanence.

Heraclitus and the Philosophy of Change

The first man on our stage is Heraclitus (535-475 B.C.), a native of Ephesus. He had the reputation of being a very bad-tempered man and we know at least that his was a sharp pen. He had a profound and outspoken contempt for just about everybody. According to him, Homer deserved to be whipped, and Pythagoras was an imposter. “Most men are bad,” is one statement attributed to him.

As a reflection of his contempt for the run of mankind Heraclitus took little pains to make himself easily understood. He deliberately wrote in riddles, declaring that if you want gold you have to dig for it. He earned the title “the obscure” or “the dark” from the people of his day.

Heraclitus is still known as the philosopher of change. Change, for him, was the key to the universe. Nothing is so universal as the fact of change, from the movement of the heavenly bodies to the rhythm of growth and decline among terrestrial bodies. You plant an acorn, for example, and in a few years you have a towering oak tree. The question naturally arises, Is there any of the original acorn left in the oak tree? Humans change. The change is going on while this sentence is being read. We are some seconds older. We are not exactly the same person as when we arose this morning. Still less are we the person we were last year, and much less the person we were fifteen years ago. It is very difficult to see the eight pound infant in the two hundred pound adult with the double chin. Can we say there is any of the original infant left in the grown adult?

Even lifeless bodies are always changing. A thousand invisible hammers are tearing away at the objects around us—tables, chairs, books, buildings. What would happen if they were left to themselves for a thousand years, for five thousand years? The tombs of ancient kings who were buried with their furniture and their treasures long ages ago tell us that these things all crumble to dust. And a little reflection will remind us that this wasting away does not happen in one sudden moment, but that it is a continuous process that is going on even now. Even such solid-seeming things as gold and platinum, we know from modern physics, are centers of movement and pulsation, with the particles of the atom whirling around the central nucleus as the planets whirl around our sun.

“All things are in a state of flux,” declared Heraclitus. Reality is a torrent of change and just as “you can never step into the same river twice,” so too the world is never the same at successive instants. Heraclitus used the example of a burning candle to illustrate his point. The flame of the candle seems constant, yet we know that the solid body of the candle is slowly melting and being taken up into the flame of the candle where it is changed into smoke.

The world itself changes just like the flame of the candle. In fact, fire is the basic stuff out of which everything is made. Heraclitus chose fire as the ground of all things because it was the element that seemed most “alive.” Things are always changing into and out of fire. Imagine the smoke from the burning candle turning back into wax and you are fairly close to Heraclitus’ idea of the rhythm of change. The four elements are the various forms of fire: earth, the lowest and heaviest form of matter, melts into water; water changes into air, and air into fire. This is what Heraclitus called the upward path. The reverse changes of fire into air, water, and earth constitute the downward path.

The proportion of the elements varies in the course of endless changes, the varying proportions of earth, water, air, and fire accounting for the changes of day and night, and the various seasons. The preponderance of moisture, for example, is the cause of winter, the encroachment of dryness the reason for summer.

What happens in the great world happens also in the little world of man. (Heraclitus too adopted the comparison of man and the world which is expressed by the notions of the microcosm and the macrocosm.) Man’s body is mainly earth, but it is constantly changing into water, air, and fire, which is the soul; then, just as in the case of the great world itself, the fire changes back into air, moisture, earth. Sleep is due to the excessive proportion of moisture, as we can see in the case of drunkenness. Waking is caused by the restoration of the proper balance between the elements. If moisture, or any of the elements, gets the upper hand over the others, death follows.

As far as the appearances of things are concerned, then, it seemed to Heraclitus and his followers that we cannot name a single thing in the world around us which is not undergoing change. And, as Heraclitus furthermore stressed, if a thing is changing it is not the same from one moment to the next. In the very act of naming it, it is becoming something else. Things don’t last long enough even to be named. They don’t have even a relative permanence.

Parmenides and the Philosophy of Permanence

Shortly after Heraclitus had...