![]()

V

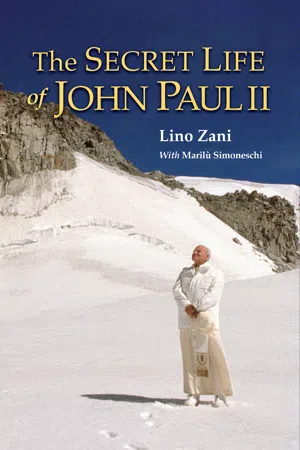

SIGNS OF HOLINESS

IN SEPTEMBER, a couple of months after the encounter on the Adamello, my brother Franco and I went to Rome to see the pope at the Vatican. The appointment had been organized in an informal and hasty manner thanks to the intercession of trusty Don Stanislao.

It was wonderful to see the Holy Father again. We were very emotional, and he, in an excellent mood, cracked one joke after another, entertaining us with his subtle irony. We spent half an hour with him, and later found out that this had meant keeping an African head of state waiting. We came away lighthearted, thinking how great it was to have a pope as a friend.

It was even more thrilling to meet with him shortly before Christmas of that same year. Around the middle of December, we received a telephone call informing us that the Holy Father would like us to visit his private quarters for an Advent Mass and to exchange Christmas greetings. We were specifically told that he wanted to see the whole family.

The preparations began: proper attire, travel arrangements, accommodations. Apart from me, there were my parents, Carla and Martino, my brother Franco and his wife, our sister Renata and her husband, and our younger sister, Miriam. The appointment was set for seven in the morning on December 22. Our alarm clock went off two hours early, even though we were staying very close to the Vatican, in a hotel on the Via della Conciliatzione. We were all tremendously excited. It was one thing to attend the Mass said there at our house, like a simple family prayer or an Easter blessing. It was another thing to be admitted to the most important liturgy in the world, there in the heart of Christendom. What we would have to say and do, how we would have to do it, when we would speak, how we would approach him and the Eucharist—it all seemed so complicated. And yet everything would turn out to be beautiful, solemn, and simple.

We entered through the Bronze Gate, to the right of the colonnade, climbed the grand stone staircase, and passed the checkpoint of the Swiss Guards, dressed in their distinctive colorful uniforms. We walked across the courtyard of Saint Damasus, a highly evocative spot that has seen kings, queens, and heads of state from all over the world pass through it. We went up to the third floor of the apostolic palace, and walked down the hallway on the left, the one of the Third Loggia. From there we entered the pope’s private quarters. We went through a door into a wide vestibule leading to a sitting room next to the private library. We were made to wait in the little office reserved for Don Stanislao. He welcomed us himself, and after we greeted each other joyfully he brought us into the pope’s private study, at the window of which he appeared every Sunday to recite the Angelus, and where he gave the Urbi et Orbi blessings.

We then entered the private chapel next to the pope’s bedroom. He was already in place, in his white cassock and green vestments. We took our places in silence. In addition to us, there were about twenty priests of various nationalities, who were about to leave for mission territories. If one were to ask me what morning Mass with the pope is like, and what procedures are followed, or how long it lasts, I could only reply that it is a truly religious ceremony marked by the greatest simplicity, yet very intense.

There was no trace of official imposition, no embarrassment, and we suddenly realized that it was entirely natural for us to be there all together, intent on watching him, attentive to his movements and their spiritual message. The only peculiarity of that Mass was that there was no homily. Before the consecration of the Eucharist, the pope recollected himself in deep meditation. It was a moment of intense absorption, although less pronounced than what I had seen when he was sitting on the rock at the top of the Passo di Lares.

Many times, especially as his beatification was approaching, I asked myself what were the signs of his holiness. I have tried to shed light on them, poring over my memories to understand better. I have tried to do this with lucidity, with a spirit of observation and rationality, without getting carried away by emotion. And so I can assert with absolute certainty that one of the signs that I encountered was precisely what he was able to transmit to those who had the immense privilege of attending one of those intense, anguished, weighty prayer sessions. It was as if he took hold of the hearts of those present, as if he changed the structure of time and place.

Here’s an example: it could have been a few minutes or even hours, but afterward one had the sense that everything had happened fast, like lightning. What lasted the whole day and even much longer was, instead, a sensation of peace, of floating over all the things of life. It was as if one had succeeded in distancing oneself from problems, anxieties, and worries, although without having forgotten them.

The main effect of his holiness was precisely that of transmitting a stream of unexpected courage to face one’s own life, whatever it was like. For a little while after having been with him, one became intrepid, impermeable to the evil of sufferings, unharmed by fear.

“Be not afraid! Open, rather, throw the doors wide open for Christ.” You will remember that he had already said this on that Sunday of October 22, 1978, the day of his installation.

After the Mass, we were led out of the private chapel and accompanied to a room across from the dining room. The pope changed, said goodbye to the other guests, and came back to us, greeting each of us very warmly, one by one. He then told us that he would like us to have breakfast together.

We went into the adjacent dining room, where the table was already set. Don Stanislao, naturally, was also present. We were served milk, coffee, and tea, and some exquisite homemade coffee cakes prepared by the Polish sisters of the Congregation of the Sacred Heart, who together with their superior, Tobiana Sobodka, always took care of John Paul II with love and discretion. They were the ones who served us at table, attentive but not intrusive, and gentle, like real guardian angels. As always, the pope showed an interest in each one of us, calling us by name and asking for news and details about everyone. He wanted to know how things were going, how work and life were up there on the mountain. He asked us how we were going to spend the Christmas holidays, and dwelt with evident pleasure upon his memories of the Adamello, or rather “our Adamello,” as he would call it from then on.

We left the Vatican with the sensation of having been in a dream: our whole family at breakfast with Pope John Paul II, perhaps the most beloved man in the world. Being able to converse with him as if he were a member of the family truly seemed to us the fruit of an extraordinary privilege. My mom, my sister-in-law, and my dad let loose with long and enthusiastic commentaries on the solemnity of the places we had just visited, on the unique beauty of the buildings and their interiors.

All true, but afterward I would hear in person from “my” pope how that place, so rich in history and magnificence, sometimes represented a real prison for him. At the Vatican, the successor of Peter exercised his mission as Supreme Pontiff with complete abnegation, but the man rediscovered during those moments of rest and contemplation in the mountains his most authentic spiritual closeness to God. It was therefore an immense privilege to have been a witness and companion of his trips to the mountain, in search of the exhilaration of freedom, but also of the essential, of his most authentic relationship with God.

Nearly four years later, at the beginning of the spring of 1988, I went to see him again because I was about to leave on an important expedition in Asia. I was going to climb Cho Oyu, a mountain with an elevation of 26,906 feet, situated on the border between Tibet and Nepal, a few miles from Everest. I arrived at the Vatican in the morning, and again I was admitted into his quarters to attend Mass in his private chapel. Then we had a long conversation about my upcoming adventure. He was very curious about my trip, and asked me how I would approach the climb and how I had prepared. He also wanted to know why I had chosen Cho Oyu.

I spoke to him about it at length, explaining to him that it was the sixth-highest mountain in the world, but above all that it presented breathtaking colors and views during the climb. In fact, “Cho Oyu” means “Turquoise Goddess” in Tibetan. I explained that once one reached the terminal plateau at an elevation of about 18,536 feet, one could observe up close the marvelous northern face of Everest. He also asked me about the dangers the climb presented. I told him that the greatest danger might be constituted by the ease with which one could get lost in case of fog or low visibility, from fifteen thousand feet up, in the section of the terminal plateau. Once one was past the initial rocky section, in fact, a rather flat and even stretch of terrain followed, with few visual reference points, which could cause confusion and obscure one’s sense of direction. I explained to him that like all the Himalayan mountains, this giant was not to be underestimated, and that confronting it required adequate preparation, acclimatization, and technical preparation. He listened to me with great interest, I would say almost with a touch of jealousy. It was clear that under other circumstances he would have liked to have been in my place. I would later learn how many of his memories were connected to the Tatra mountains in Poland. He told me about his camping trips, about the fact that they were coed, something very unusual for those times, and how those rocky surroundings had inspired his play The Jeweler’s Shop.

He would also tell me, with a certain touch of pride, about his and his friends’ agility canoeing over rapids, which are numerous and very swift. But I would learn about these memories of his in the years to come, when our relationship had been founded on a certain confidence. That day, however, after a long moment of reflection and silence, he said to me, “I will give you a cross to plant on that mountain. From now on, you will be our ‘apostle of the mountains.’ You must take a cross to the highest and most beautiful mountains of the world. Carrying the cross of Jesus on the mountains must be your mission.”

I was deeply struck by those words—speechless. I didn’t know what to say. But he, as usual, wasted no time and moved into action, He immediately sent for a green case from which he took a cross, about eight inches long. He blessed it and gave it to me. He said goodbye, telling me to be careful and to let him know as soon as I got back to Italy.

I got in touch with him three months later. I had endured exhaustion, the cold, storms, and temperatures of sixty degrees below zero. I had spent days and nights stuck at altitudes of over twenty thousand feet, with the wind preventing me from even sticking my head out of the tent. I had thought, as always happens, about giving up, but I was determined—and this is a switch that often “clicks” on in the heads of climbers—to reach the goal, to make it to the end no matter what. At 27,000 feet I felt a boundless sense of intoxication. I greeted the northeast face of Shisha Pangma, and in front of me was Everest.

On the summit of Cho Oyu, I planted the cross on a tripod that the Chinese had placed on the highest point. I placed it there and it seemed to me that the pope, with his immaterial yet very real presence within me, was beside me and was looking at me. I set up the camera to take a photo in that beautiful and unrepeatable moment. After I returned I went to Rome and gave the picture to the pope. He was rather touched, and said, “You see, you did it. Now you really have become the ‘apostle of the mountains’!”

Sometimes during the winter the pope went skiing, even just for a day, on the mountains of Abruzzo, in Pescasseroli or Ovindoli, or on the nearby Mount Terminillo.

I would accompany him sometimes, and we would put our skis on right away and ski for hours, at any pace, with tremendous pleasure. Most of the time the few people we saw didn’t even recognize the pope, dressed as he was in athletic gear and with his eyes concealed by sunglasses. Now and again something quite funny would happen. I remember one morning when we passed a boy of about eight years old a couple times on the ski lift. He kept looking at the pope, who smiled gently at him. At a certain point, after two or three runs, the boy came up to us and asked him point-blank, “Are you the pope?”

“Yes, do you want to ski with me?”

They rode up together several times, one behind the other on the little seats, while I enjoyed the incredible scene from a distance. I remember that at a certain point the boy went over to his mother, who was sunning herself in a chair down in the valley near the bottom of the ski lift, and shouted, “Mom, did you know I’m skiing with the pope?”

The lady just shook her head. John Paul was highly amused, and late in the morning he wanted to go say hello to her. I will never forget that woman’s flabbergasted expression—even today, she must wonder if it was all a dream!

What were not dreams at all, but intense moments of prayer and meditation, were the moments I saw over and over again, always in the mountains and always after he had made a sudden decision. He may have been joyful, bubbly, invigorated by our skiing, but all of a sudden his expression would change and turn somber, as if something was deeply troubling him. As usual, the Holy Father would speak in Polish with Don Stanislao, who would tell me, “Lino, let’s look for a good spot, John Paul wants to be alone for awhile.”

He usually preferred spots with views stretching out to the horizon, where he could put himself in the presence of the infinite. And that anguished immobility— that capacity of ascetical concentration that I have never seen any other human being maintain for so long—always came back. I believe that in those moments, which I witnessed in silence and with profound respect, he had genuine prophetic visions. At times, in fact, the pope came out of these meditations with a very troubled expression, in great distress, as if seized by preoccupation. In those cases Don Stanislao immediately approached him, and spoke with him quietly and in Polish.

I remember one time in particular when I witnessed a dramatic scene of this nature. I saw him come out of that sort of ecstasy in great agitation, shaken to the core. He and Don Stanislao spoke privately for a long time, and then we hurried back to where we were staying. It was summer, they were on vacation, and I had joined them there. By that time I understood immediately that something bad was about to happen.

A few hours later, the Iraqi army invaded Kuwait with one hundred thousand men and three hundred tanks, overcoming all resistance by the Emirate within a few hours. The emir of Kuwait, Jaber III Al-Ahmad Al-Jaber Al-Sabah, went into exile in Saudi Arabia with his family, while his brother Fahd was killed along with two hundred others. The Gulf War had begun.

At the time, I didn’t ask myself too many questions. Instead, I observed and accepted everything that was happening before my eyes with naturalness and in a spirit of faith. Now that various miracles have been recognized and attributed to him, I no longer have any doubts: in those moments, the man to whom I was bound by the greatest affection was no longer a mere man, but was “exercising” to be a saint. Foreknowledge is one of the gifts of the saints.

Much more would happen to me in the years to come. The Holy Father saved my life twice, but I will talk about this later. After that first vacation on the Adamello, John Paul II developed the habit of spending a few days in the mountains each year, often choosing Lorenzago di Cadore, a cheerful town in northeast Italy near the Passo della Mauria, whose history is also connected to the first world war. That territory, in fact, which constitutes a corridor of access from Veneto to Friuli, was the bloody theater of the armed defense of the people of Cadore against the Austrians. Every summer, when he was there, I went and joined the group that he called his “family”: Don Stanislao, Monsignor Taddeo, Luciano Cibin, Angelo Gugel, and often Arturo Mari, his personal photographer, who with delicacy and discretion captured on film those moments of such intensity and happiness.

The pope stayed in the Castello di Mirabello, situated in the woods above the town, a gorgeous location. From there we went on fantastic excursions to the Passo della Mauria, where the Tagliamento River begins...