eBook - ePub

The Life of the Blessed Virgin Mary

From the Visions of Venerable Anne Catherine Emmerich

- 411 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Life of the Blessed Virgin Mary

From the Visions of Venerable Anne Catherine Emmerich

About this book

Incredibly revealing and edifying background of Our Lady, her parents and ancestors, St. Joseph, plus other people who figured into the coming of Christ. Many facts described about the Nativity and early life of Our Lord, as well as the final days of the Blessed Mother–all from the visions of this great mystic. Impr. 411 pgs,

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

Theology & ReligionSubtopic

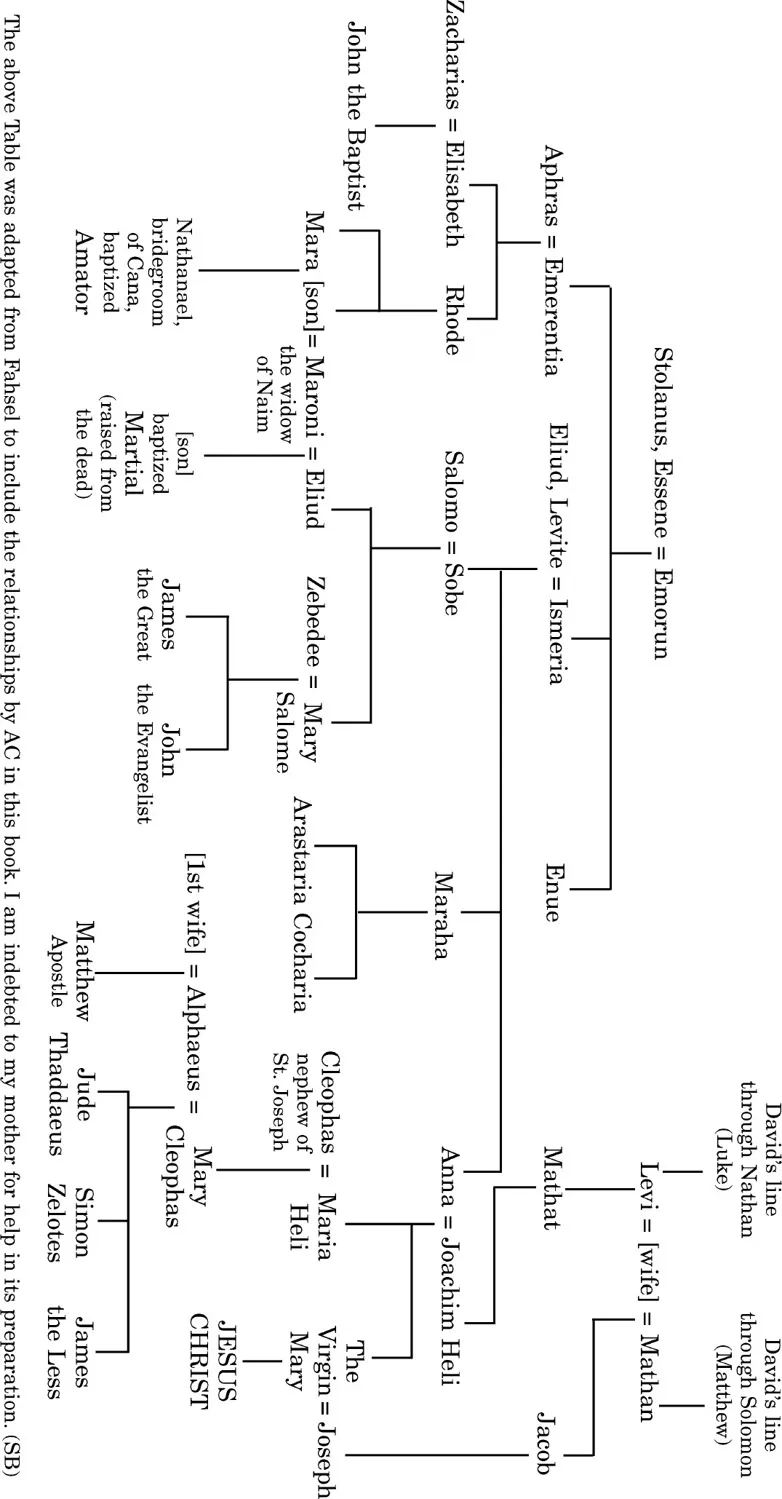

Christian DenominationsGENEALOGICAL TABLE

1.The “Pilgrim” is Clemens Brentano, who wrote down the visions at Catherine Emmerich’s dictation. These were communicated by her to him on the morning of June 27th, 1819. (Tr.)

2.It is commonly stated that such separation was required of priests on duty, and this can be deduced from Lev. 15:18 (ceremonial uncleanness contracted) and Lev. 22: 3 (ceremonial cleanness required). (SB)

3.Mass of the Fourth Sunday in Advent.

4.Communicated in July and August 1821.

5.This was taken down in August 1821 by the writer from Catherine Emmerich’s words. In July 1840, when preparing the book for printing, he asked a language expert for an explanation of the word Azkara, and was told that Azkarah meant commemoration and is the name of the portion of the unbloody sacrifice, which was burnt on the altar by the priest to the glory of God and to remind Him of His merciful promises. The unbloody sacrifices generally consisted of the finest wheaten flour mixed with oil and sprinkled with incense. The priest burnt as the Azkarah all the incense and also a handful of flour and oil (baked or unbaked). In the case of the shew-bread the incense alone was the Azkarah (Lev. 24:7). The Vulgate translates the word Azkarah alternatively as “memoriale,” “in memoriam,” or “in monumentum.” (CB)

Lev. 24:7, literally: “And thou shalt place upon the shew-bread pure incense, and it shall be for the bread as a memorial (azkarah), a burnt offering to the Lord.” The other references to the word azkarah are in Lev. 2:2, 9:16, 5:12; 6:8; Num. 5:26 in connection with the burning of a meal-offering (minhah). The connection with the Essenes remains obscure. (SB)

6.Hasid (pl. Hasidim), originally meaning “merciful” (of God), came to mean “devout” of men, and was later in Maccabean times used to designate a specific group of devout and observant Jews who joined the Maccabean party in their fight for freedom (1 Mac. 2:42). These Hasideans (Gk. Asidaioi), as they were then called, are generally believed to be the forerunners of the Pharisees (cf. Lagrange, Le Judaïsme avant Jésus-Christ, 1931, pp. 56, 272), and probably of the Essenes (Bonsirven, Le Judaïsme Palestinien, 1935, I, pp. 43, 64), both sects being mentioned by Josephus in Maccabean times (Ant., XIII, v, 9). (SB)

7.They were called Essenoi by Josephus, Esseni by Pliny, and Essaioi by Philo (and six times by Josephus). The origin of the name is uncertain (cf. Lagrange, op. cit., p. 320). Their way of life, as described by AC, is for the most part fully attested by the contemporary historian Josephus (BJ, II, viii, 2-13), as well as by Philo (Quodomnis probus liber sit, 75-88). Pliny’s remarks (Hist. Nat., V, 17) attribute to the Essenes an antiquity of “thousands of years.” There is no other evidence of an antiquity beyond Maccabean times. (Most texts in Lagrange, op. cit., pp. 307-17.) Passing references by Josephus are in Ant., XIII, v, 9 and XVIII, i, 5. (SB)

8.The spiritual head on Mount Horeb, Archos, is not mentioned in any of the documents. (SB)

9.It is well known that the Essenes refused to sacrifice animals, but the ritual of releasing them (as described by AC) is one of the few matters that is not documented. In Lev. 14:53 the Law prescribed the freeing of a bird after purification from leprosy, and in 16:22 the ritual of the scapegoat, which was to “carry away all their iniquities into an uninhabited land.” (SB)

10.The little daughter of Catherine Emmerich’s brother, who came from the farm of Flamske near Koesfeld to visit her at Dülmen in the winter of 1820, was seized with violent convulsions occurring every evening at the same time and beginning with distressing choking. These convulsions often lasted until midnight, and Catherine Emmerich, knowing as she did the cause and significance of this and indeed of most other illnesses, was greatly affected by her niece’s sufferings. She prayed many times to be told of a cure for them, and at last was able to describe a certain little flower known to her which she had seen St. Luke pick and use to cure epilepsy. As a result of her minute description of the little flower and of the places where it grew, her physician, Dr. Wesener (the district doctor of Dülmen), found it; she recognized the plant which he brought her as the one she had seen, which she called “star-flower”, and he identified it as Cerastium arvense linnaei or Holosteum caryophylleum veterum (Field Mouse-ear Chickweed). It is remarkable that the old herbal Tabernamontani also refers to the use of this plant for epilepsy. On the afternoon of May 22nd, 1821, Catherine Emmerich said in her sleep: “Rue [which she had used before] and star-flower sprinkled with holy water should be pressed, and the juice given to the child, surely that could do no harm? I have already been told three times to squeeze it myself and give it to her.” The writer, in the hope that she might communicate something more definite about this cure, had, unknown to her, wrapped up at home some blossoms of this plant in paper like a relic and pinned the little packet to her dress in the evening. She woke up and said at once: “That is not a relic, it is the star-flower.” She kept the little flower pinned to her dress during the night, and on the morning of May 23rd, 1821, she said: “I had no idea why I was lying last night in a field amongst nothing but star-flowers. I saw, too, all kinds of ways in which these flowers were used, and it was said to me, ‘If men knew the healing power of this plant, it would not grow so plentifully around you.’ I saw pictures of it being used in very distant ages. I saw St. Luke wandering about picking these flowers. I saw, too, in a place like the one where Christ fed the 5,000, many sick folk lying on these flowers in the open air, protected by a light shelter above them. The plants were spread out like litter for them to lie on; and arranged with the flowers in the center under their bodies, and the stalks and leaves pointing outwards. They were suffering from gout, convulsions, and swellings, and had under them round cushions filled with the flowers. I saw their swollen feet being wrapped round with these flowers, and I saw the sick people eating the flowers and drinking water which had been poured on them. The flowers were larger than those here. It was a picture of a long time ago; the people and the doctors wore long white woollen robes with girdles. I saw that the plants were always blessed before use. I saw also a plant of the same family but more succulent and with rounder, juicier, smoother leaves and pale blue blossoms of the same shape, which is very efficacious in children’s convulsions. It grows in better soil and is not so common. I think it is called eyebright. I found it once near Dernekamp. It is stronger than the other.” She then gave the child three flowers to begin with; the second time she was to have five. She said: “I see the child’s nature, but cannot rightly describe it; inside she is like a torn garment, which needs a new piece of stuff for each tear.” (CB)

11.These were Catherine Emmerich’s words on August 16th, 1821. The names are here written down as the writer heard them pronounced by her lips, and also her explanation “noble mother.” When the writer read this passage to a language expert in 1840, the latter said that it was indeed true that Em romo means a noble mother. (CB)

Em ramah could mean “noble mother,” though the adjective ram, usually meaning materially “high” or else “proud,” has no obvious parallel in a proper name, except perhaps in Amram (the father of Moses), which may mean “noble uncle.” (SB)

12.She unquestionably meant that these herbs were the same as those mentioned by Eusebius in his ecclesiastical history, Book VII, Chapter 18, which he says grew round the statue of Jesus Christ put up by the woman of Caesarea Philippi, who was cured of the issue of blood. The plants acquired the power of healing all kinds of sicknesses as soon as they had grown high enough to touch the hem of the statue’s garment. Eusebius says that this plant is of an unknown species. Catherine Emmerich had spoken before of the statue and of these plants. (CB)

13.In July 1840, some twenty years after this communication, as this book was being prepared for the press, the writer learnt from a language expert that the cabalistic book Zohar contains several references to this matter. (CB)

The Zohar is a rabbinic book, claiming descent from Rabbi Simeon ben Yohai (second century), in the form of a commentary on the Pentateuch, interpreting it throughout, in an enigmatic and esoteric style, according to a mystical sense. The Zohar first became known through the 13th-century Rabbi Moses de Leon, who has often been accused of fabricating the whole thing. Present-day opinion, however, suspends judgment, while emphasizing that the Zohar shows evidence of being a compilation of texts and fragments whose composition probably extended over many centuries, and which is likely to enshrine teaching of the greatest antiquity. The Zohar is one of the principal sources of spiritual interpretation among the Jews, and its main theme may be said to be the significance of every detail in sacred history, and the symbolic reflection in this world of the eternal realities of Heaven. With regard to its connection with the statements of AC, see further n. 33, p. 44. (SB)

14.Catherine Emmerich pronounced these and all other name-sounds with her Low-German accent and often hesitatingly. Her pronunciation, she said, only resembled the real names, and it is impossible to be sure how correctly or incorrectly they have been written down. It is all the more astonishing to find elsewhere long afterwards similar names for the same persons. The following is an instance. Several years after Catherine Emmerich’s death the writer found in the Encomium trium Mariarum Bertaudi, Petragorici, Paris, 1529, and in particular in the treatise De cognatione divi Joannis Baptistae cum filiabus et nepotibus beatae Annae, lib. III, f. lii, etc., attached to it, that St. Cyril, the third General of the Carmelite Order, who died in 1224, mentions in a work concerning the ancestors of St. Anne similar visions of branches, buds, and flowers seen by the prophet of whom counsel was sou...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Copyright Page

- CONTENTS

- PREFACE TO THE PRESENT EDITION

- EXTRACT FROM THE PREFACE TO THE GERMAN EDITION

- OBSERVATIONS ON THE SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES

- I. OUR LADY’S ANCESTORS

- II. MORE ABOUT THE IMMACULATE CONCEPTION THE BIRTH OF OUR LADY

- III. THE PRESENTATION OF THE BLESSED VIRGIN IN THE TEMPLE

- IV. THE EARLY LIFE OF ST. JOSEPH

- V. A SON IS PROMISED TO ZACHARIAS

- VI. MARRIAGE OF THE BLESSED VIRGIN TO JOSEPH

- VII. THE ANNUNCIATION

- VIII. THE VISITATION

- IX. ADVENT

- X. THE BIRTH OF OUR LORD

- XI. THE JOURNEY OF THE THREE HOLY KINGS TO BETHLEHEM

- XII. THE PURIFICATION

- XIII. THE FLIGHT INTO EGYPT AND ST. JOHN THE BAPTIST IN THE DESERT

- XIV. THE RETURN OF THE HOLY FAMILY FROM EGYPT

- XV. THE DEATH OF THE BLESSED VIRGIN AT EPHESUS

- XVI. THE BURIAL AND ASSUMPTION OF OUR LADY

- GENEALOGICAL TABLE

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Life of the Blessed Virgin Mary by Anne Catherine Emmerich in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Christian Denominations. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.