![]()

Chapter 1

The Beginnings of Psychological Practice

Consider the following three case studies. First, a boy in Patterson, New York, was taken by juvenile court authorities to a psychologist for assessment. The psychologist examined him and told the authorities that his test results indicated that the boy had a strong disposition to steal. That information proved crucial to the juvenile justice system because the boy had been caught stealing on several occasions.

Second, there was the case of Harriet Martineau, who suffered from depression. She was socially withdrawn, lacked energy, and often didn’t eat. She had seen several physicians who had prescribed drugs for her treatment, but the depression continued. After five years of unsuccessful treatments, her physician expressed hopelessness that she could ever be cured. On the advice and recommendations of some friends, Martineau went to a psychologist, Spencer Hall. After four months in treatment with Hall, Martineau pronounced herself cured, her energy and zest for life restored.

Finally, there was the case of Charles, whose childhood was an unhappy one. Because of family debts he began work in a factory at the age of 12. Deprived of a formal education, he sought to teach himself. Eventually he obtained a job as a reporter for a small newspaper. Like many young men he was uncertain what he wanted to do in life. A psychologist who examined him said that he had a reflective intellect, had great powers of observation, was a shrewd reasoner, had a considerable mastery of language, and displayed great wit and humor. The psychologist noted that his temperament and talents were well suited to success as a writer.

Each of these vignettes describes actual cases in which psychological services were being used. In the first case, examination of the boy determined that he was a thief. In the second case, Ms. Martineau was cured of her depression. And finally, a vocational assessment of Charles indicated that he might have success as a writer. Yet, in fact, no psychologists were involved in any of these cases, at least no psychologists as we would define them today, because each of the cases just described took place in the mid-1800s, long before the science of psychology arrived in America.

The “psychologist” in the first case was a phrenologist who measured the bumps on the skull of the young boy to discover that the brain area said to be responsible for “acquisitiveness” was quite large, thus indicating his propensity to steal. In the second case, Ms. Martineau was treated by a mesmerist who used techniques similar to hypnosis to eliminate her depression. Finally, in the third case, Charles’s face was examined by a physiognomist, someone who judged an individual’s personality and intellect based on the person’s facial features, a pseudoscience known as physiognomy. Actually Charles’s face was not examined in person when he was a young man. Instead, the physiognomist studied it from a photograph when Charles was in his 50s and had already written Oliver Twist, David Copperfield, and Great Expectations. Thus armed with such knowledge, it was perhaps easy for the individual to predict that Charles Dickens had the temperament and talents to be a successful writer.1 In the pages that follow, we discuss these pseudoscientific approaches that are part of the history of psychological practice.

This book is a historical account of the development of psychological practice in America, that is, the history of psychology’s evolution as a profession. America is not the only place where a profession of psychology developed, but it is the focused locale of this history, selected in part to make this history a manageable one. It is estimated that there are more than 174,000 psychologists in the United States today and that the great majority of those work in some kind of applied setting, including many in independent practice. There are clinical psychologists, counseling psychologists, school psychologists, industrial/organizational psychologists, forensic psychologists, health psychologists, sport psychologists, educational psychologists, consumer psychologists, engineering psychologists, media psychologists, geropsychologists, community psychologists, and environmental psychologists, to name most of the applied psychology specialties. The 21st-century psychological specialties owe their origins, in large part, to the emergence of scientific psychology in the late 19th century. Yet it is clear that many of these practice activities existed in the 19th century, before there were psychological laboratories and scientific psychologists. These early practitioners sometimes used the label “psychologist”; more commonly, however, they were known as phrenologists, physiognomists, characterologists, psychics, mesmerists, mediums, spiritualists, mental healers, seers, graphologists, and advisers. There were no licensing and certification laws at the time, so all who wanted to offer “psychological” services did so and could call themselves anything they wanted.

It is important to grasp the significance of these precursors to modern psychology. Too often the current understanding of psychology’s history is that “there was a science of psychology and it spawned the practice of psychology.” But clearly there was a practice of psychology, if not a profession, long before there was a science. Indeed one can find evidence of psychological interventions dating to the beginnings of recorded history. That there have been individuals throughout human history who sought to treat psychological problems or advise about psychological questions should not be surprising. When there have been human needs, there have been individuals willing to meet those needs. Today we expect professions like medicine, nursing, and psychology to be based on the sciences that underlie those professions. Yet all of those professions existed before there was science. Such services were needed and so individuals offered their potions, their rituals, their laying on of hands, and their advice to bring aid to their clients. Thus the story of the profession of psychology is one that is thousands of years old. For our purposes here, however, we will begin the story in the 19th century.

As we have noted, in the 1800s in America, individuals were engaged in exactly the kinds of psychological activities in which professional psychologists are engaged today. The theories are different and the methods are different, the education and training are different, and there are contemporary laws that regulate psychological practice for protection of the consumer. Yet the practitioners of the 1800s were engaged in the same “helping” activities, trying to assist people to enjoy success, health, and happiness in school, in the workplace, and in everyday life. This chapter tells the story of some of these early practitioners and shows how their work relates to contemporary psychological practice.

Although the Civil War would tear the nation apart in the middle of the century, the 19th century was largely one of optimism, if not prosperity, for many Americans, at least those of European origins. Many had come to the New World in search of a better life and many had found it in the abundant opportunities of agriculture, commerce, and the trades. Land was still cheap for those adventurous enough to push westward, and dreams of great fortunes to be made were reinforced by tales from the great cities of the East and from the goldfields of the West. Of course there was much poverty and human misery as well, particularly in the cities, but this was America, the land where dreams of riches and success sometimes did come true. In pursuit of their dreams, Americans put their faith in education and religion as a means for personal and financial betterment. Yet other institutions offered hope as well, including a host of practitioners of varying pseudosciences that offered personal counseling that promised health, happiness, and success.

Having Your Head Examined: Phrenology

In 19th-century America, “having your head examined” was big business, largely due to the enterprising efforts of two brothers whom we discuss later. Having your head examined meant phrenology, certainly the best known of the applied psychologies of the 19th century. Phrenology originated with a German physician and anatomist, Franz Josef Gall (1758–1828), who argued that different parts of the brain were responsible for different emotional, intellectual, and behavioral functions. He believed that talents and defects of an individual could be assessed by measuring the bumps and indentations of the skull caused by overdevelopment or underdevelopment of certain brain areas. Phrenology was popularized by Johann Spurzheim (1776–1832), who collaborated with Gall on anatomical research on the brain and later promoted his own brand of phrenology consisting of 21 emotional faculties and 14 intellectual ones. Spurzheim died in Boston in 1832 on a lecture trip popularizing phrenology. His work was continued by a Scottish lawyer turned phrenologist, George Combe (1788–1858), whose 1828 book, The Constitution of Man, established him as the leading voice of phrenology. Combe continued Spurzheim’s American lecture trip, selling his books and establishing phrenological societies in the major cities of his travels. Although by 1832 there were critics of the scientific legitimacy of phrenology, Americans, by and large, accepted it, and its proponents, particularly Combe, were praised for the practical benefits to individuals and society that phrenology offered.

Combe adhered to the categorization of 35 faculties as described by Spurzheim. In describing the basis in 1835 for his practical phrenology he wrote:

Observation proves that each of these faculties is connected with a particular portion of the brain, and that the power of manifesting each bears a relation to the size and activity of the organ. The organs differ in relative size in different individuals, and hence their differences of talents and dispositions. This fact is of the greatest importance in the philosophy of man … These faculties are not all equal in excellence and authority … Human happiness and misery are resolvable into the gratification, or denial of gratification, of one or more of our faculties … Every faculty is good in itself, but all are liable to abuse. Their manifestations are right only when directed by enlightened intellect and moral sentiment.2

What phrenology offered was not only the cranial measurement that identified the talents and dispositions but, more important, a course of action designed to strengthen the faculties and bring the overall complex of emotional and intellectual faculties into a harmony that would ensure happiness and success. This was practical phrenology, that is, phrenology applied.

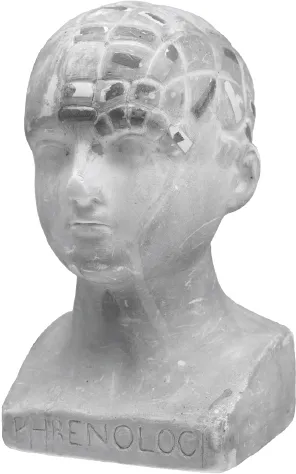

In the United States, no one was more strongly identified with applying phrenological “science” than the Fowler brothers, Orson (1809–1887) and Lorenzo (1811–1896), who opened clinics in New York, Boston, and Philadelphia in the late 1830s. They franchised their business to other cities, principally through the training of phrenological examiners, and provided phrenological supplies to the examiners, such as phrenology busts for display and teaching, calipers of varying sizes for measurements, display charts for the wall, manuals to sell to the customers, and, for the itinerant phrenologists, carrying cases for tools and supplies (see Figure 1-1). They began publication of the American Phrenological Journal in 1838, a magazine for phrenologists and people interested in phrenology, which enjoyed an existence of more than 70 years. For years its masthead carried the phrase “Home truths for home consumption.”

Figure 1-1. A 19th century phrenology bust. Phrenologists often kept these in their offices for clients to see. Today, original phrenology busts sell for thousands of dollars.

Some historical accounts have stated that the Fowlers were unconcerned with the arguments over the scientific validity of phrenology, and instead simply accepted it as valid. Their magazine, however, was filled with articles and testimonials intended to attest to the scientific basis of their subject. The Fowlers and others dedicated to phrenology recognized that it was not an accepted science, and there were some efforts aimed in increasing its respectability. For example, several of the phrenological societies, with the support of the Fowlers, sought to have phrenology taught as one of the sciences in the public schools and offered as a subject in colleges. Such efforts were not successful. The rejection of the scientific community notwithstanding, the Fowlers never doubted the validity of phrenology, at least not in public, and they promoted the subject as divine truth, selling its applications. They “did a thriving business advising employers about employees, fiancés about fiancées, and everyone about himself.”3 Their business also included public lectures; classes in phrenology for those wishing to take up the profession, but also classes for ordinary curious citizens, including children; and countless publications including books, pamphlets, and magazines.

Giving examinations or “readings,” as they were often called, was the business of the phrenologist. Some operated from clinics where clients could make appointments for their examinations. A phrenologist might test a potential suitor at the request of an anxious father. Parents also sought out help for raising children, especially children who presented behavioral problems. Couples contemplating marriage might be tested for compatibility. Individuals could be tested for vocational suitability. Businesses might use the phrenological clinics as a kind of personnel department, matching individuals to jobs or selecting workers with managerial skills or sales skills. In areas where clinics did not exist, there were traveling phrenologists who advertised their arrival in advance and rented space for the duration of their stay.4

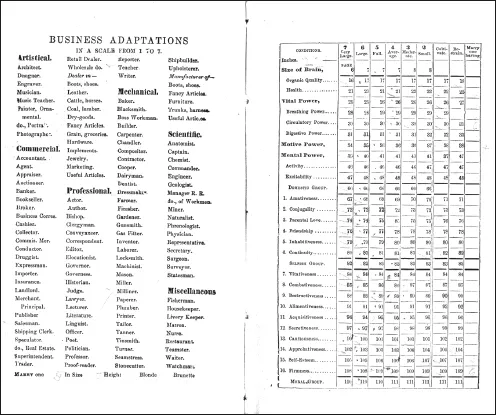

One of the creations of the Fowler brothers, as part of their “franchising,” was the “self-instructor” manual, first published in 1859. These cloth-bound books of approximately 175 pages were to be sold to the clients for 50 cents. By 1890 it was estimated that more than 250,000 copies of that manual had been sold. The title page of the book had a space for the name of the examiner and the name of the person being examined. The next two pages were tables of faculties that were to be marked by the examiner on a scale of 2 (small) to 7 (very large). In addition, beside each of the faculties were two boxes, one marked “cultivate” and the other “restrain” (see Figure 1-2). The examiner would mark the appropriate box for those faculties requiring self-adjustment. The examinee would leave with the book, including the marked exam pages (the tables), and thus be able to use the data in the tables to refer to the relevant sections of the book where help would be offered in cultivating and restraining various faculties. For example, if the “destructiveness” faculty were shown to be too large, the manual advised:

Figure 1-2. A page from O. S. Fowler’s 1869 book, The Practical Phrenologist, ...