![]()

RIFF

1/VEE’S SNACKETTE

Shake Keane was back home in St Vincent working as a teacher when I first met him in 1979. In his lunch hour, we would occasionally retreat to the quiet of Vee’s Snackette, a tiny bar on the corner of busy Bay and James Street in the island’s capital, Kingstown. The bar, surrounded by shops and government offices, was close to the school where Shake was then teaching. (The entire corner block is now a bright but ugly KFC franchise.) Vee’s had only two windows, one looking out onto each congested street. Smaller than a one-car garage, the bar was a simple room with a garish melamine-coated counter and three high wooden stools. We were the only customers. Miss Vee, a sturdy, no-nonsense lady, would put out a petit-quart bottle of rum and a small bowl of ice for me. Shake’s lunch comprised three bottles of Guinness. She would then leave us alone as she scurried around in a back room.

We exchanged returnee gossip about life in England of the 1960s and the effect of coming back to St Vincent. By this time Shake was sceptical about his return. He had abandoned his flourishing jazz career in Europe and lost out to political manoeuvring in St Vincent over the post he had most wanted and had returned to implement — Director of Culture for St Vincent and the Grenadines. Sacked from this job after two years and with no other source of income, he felt compelled to accept the first vacant post and became Principal of Bishop’s College, a grand name for a small secondary school in Georgetown, the island’s second town in the northern Windward district. It seems that even in the relative tranquillity of teaching disaster lurked. At one of our meetings he described almost losing his life when one evening, during his time as Principal, he went to turn on an electric lamp and was hurled across his office. Faulty wiring.

Shake was by then in his early fifties; tall and broad, around six foot four and somewhat shaggy in appearance. His size was emphasised by his characteristic loose-fitting clothing above brown latticed leather sandals. By this time he had a luxuriant grey beard and a thinning head of hair. He moved slowly when the pain of gout struck. A large pair of spectacles rested on his nose below heavy grey eyebrows. Between his long delicate fingers he invariably held a roll-up cigarette. He spoke in a deep baritone voice. This apparently fierce demeanour was softened in conversation by an unassuming smile that came quick and easily.

Vee’s Snackette looked directly onto the street. Passersby would see him there and hail the famous musician and returned fellow Vincentian. A celebrated figure in the island, he was used to this public show of interest and would often be stopped in the street. A brief chat was a public sign of connection to a man of international stardom. One lunchtime, a young stevedore, hot and sweaty from the nearby docks, entered the bar:

‘Mista Car-heen! Mista Car-heen! ’Cuse me sar. Ah have one sar. Don’t mind the clothes all ragga, sar. I just off the jetty. You could hear me sar? Dis one goin be good sar. It go so…

I was liming on the block

wid de boys from de rum shop

is then I bounce up big Mary

them days she frennin Big Nancy’

‘OK, OK, pal, enough.’

‘It have plenty more verses sar. You like how it going? You could help me fix it up sweet, sweet? Put a lil chorus. Get recording contract and ting…. Or even… a lil drink, den sar? Me troat dry.’

Shake bought him the drink.

Supplicants came in other forms. At one of our meetings I myself showed up with a poem that I’d written. Without hesitation he took out a pen and began deleting words and rearranging its lines, circling sections with arrows going first in one direction then another to different parts of the page, instinctively aiming at bringing the page alive. I like to think I learned something about poetry firsthand from Shake.

At this stage of his life he had been back in St Vincent for six years, after more than 21 years away, first in London then in Germany. Other locations, especially New York and Norway, were to follow. These movements suggest an itinerant — a wanderer who was both framed and influenced by the twentieth century, his lifespan stretching from 1927 to 1997. Indeed, he absorbed and was absorbed by many of the currents flowing through the century. In his chosen fields, especially jazz and poetry, he not only understood them but knew how to excel in them.

Three twentieth-century currents were important in shaping his individual talents and personality. The first of these was the rise of nationalism in the Caribbean. Shake grew up and lived through a time when regional and island national sentiments were at their strongest — expressed in demands for self-government, the rise and fall of regional federation and, finally, the achievement of island-based political independence. This nationalist current was also flowing around the world, touching the colonies from the Caribbean to Africa and Asia. It brought with it political change and a sense of the importance of nation-making which no thinker of the twentieth-century Caribbean could ignore. But when Shake departed St Vincent for England in 1952, the island was still a colonial outpost; only one year earlier it had experienced its first general election under adult suffrage. When he returned in 1973, it was a few years after the island had attained Associated Statehood with Britain (1969). This was, in effect, when locally elected politicians gained control of the island’s resources and budget, taking over from the British. Six years after his return, St Vincent gained full political independence. If, as a young man, Shake had left a colony, he returned to a place in which local people vied for influence and power and local party politics was ruthless. He returned, therefore, to a different island from the one he had left.

The second great current in which Shake was caught up was the experience of migration. The question facing all migrants of ‘where is home?’ becomes especially urgent for a doubly displaced person. As someone who spent the first 25 years of his life in St Vincent, Shake was born into one diaspora. He then lived in England and in Europe for 21 years as a member of another; he returned to his birthplace for eight years before migrating yet again to live the last 16 years of his life in New York. His return to St Vincent captures a common dilemma experienced by many migrants — the desire to offer service ‘back home’ versus self-fulfilment in the adopted country. When such an itinerant is a sensitive professional musician for whom travel to different venues and countries is almost a daily constant, the question of home and homecoming has even more resonance. Not surprisingly, home and the challenges of migration are important themes in his poetry. His early writing begins by celebrating place before becoming, later, a poetry of displacement, playing with multiple positions in relation to the conundrum of home. In tracing this second contextual current we shall see how Shake’s physical movements and creative responses constitute a form of mapping.

The third current that shaped his identity was masculinity. By masculinity I do not mean a fixed and limited way of behaving — as though there were only one way to ‘be a man’ — but a range of performances, as man, musician, teacher and poet, through which he searched for a role and a sense of self. His masculinity was tested by his failure to realise his full potential in the jazz world of the 1960s, modest recognition for his poetry, and finally a conventional and serial dependence on the women closest to him. Sometimes the performances coalesced and sometimes they contradicted one another. These currents — nationalism, migration and masculinity — are, of course, intimately connected. Taken together, they have a peculiar power in animating Shake Keane’s life.

At the same time, his mature performances, especially as musician and poet, are shaped by innovative presentations that are difficult to pin down. In this way he disrupts the clear lines of demarcation between styles and genres that critics often require. Located at the crossroads between jazz and poetry, Shake’s most significant achievement was ultimately a blurring of the boundaries between these two art forms.

![]()

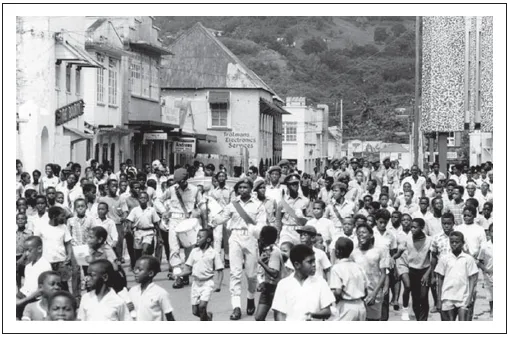

St Vincent Grammar School Cadet Band, Halifax Street (Back Street), Kingstown, 1950s. (Courtesy Clifford Edwards)

![]()

RIFF

2/‘BLESSED LITTLE HOME-HOME ISLAND’

We were children

when corked hats and plumed feathers

were among the heights of fashion

when you walked to church to hear a preacher’s sermon

and teaching was a serious profession

clinking the keys to our future.

‘Shake’ Keane was born Ellsworth McGranahan Keane on 30 May 1927 in Kingstown. He was the third son and fifth of seven children of Charles E Keane (1869-1941) and Dorcas Maude née Edwards (nd - 1963) widely known as ‘Jessie’. The total number of children that Charles fathered is uncertain — Shake claimed ‘many’ half siblings. He said that his father had been married twice before his marriage to Jessie. The registry office lists only six children from the marriage of Charles and Dorcas. His older siblings were Hadassah Magdalin Roxann, Theodore Vanragin, Edna Elaine, McIntyne Wilberforce, then there was Shake, Donny (unlisted) and Darnell Mendelssola. Certainly, Charles and Jessie were attracted to grand names for their offspring.

The family was culturally rich but economically poor. His father was a self-educated man who managed money badly and held a variety of jobs. Two were significant: he worked at different times as an estate overseer and as a corporal in the Royal St Vincent Police. In the countryside, where Charles was based before moving to Kingstown, both jobs held authority and power. According to Shake, these positions of local status also accounted for Charles’s substantial but unquantified extended family.

Music as an interest came about by chance while Charles was living and working in the countryside. The three prominent positions in the island’s rural villages at this time were the police corporal, the school principal and the estate overseer. With few diversions and no electricity, these three authority figures would get together most evenings. As Shake told it, the Principal, a Mr Drayton, an able musician from Barbados, offered to teach Charles the rudiments of music. Charles had an aptitude and soon could read music, hold a note and play the trumpet. And so music was born as an occupation in the Keane household. It is not known what year Charles moved to Kingstown, but both the marriage of Charles and Dorcas as well as the birth of their first child were officially registered in Kingstown in 1916.

It is possible that in recognition of the family’s religious affiliations as Methodists and love of music, Charles and Dorcas gave their third son the middle name of McGranahan after James McGranahan, the nineteenth-century American composer of hymns, whom Charles admired. The first name, Ellsworth, popular in the first decade of the twentieth century, is derived from the Old English name Ellias and evokes nobility. With names such as ‘Ellsworth’ and ‘McGranahan’, it is perhaps not surprising that he was more often known in his early years by his nicknames: firstly, ‘Muz’, possibly short for ‘music’ given his public performances at an early age, and later ‘Shake’. He answered to ‘Muz’ Keane throughout his early school and teaching days and even when signing letters to friends. But over time, ‘Shake’ was the name that stuck. There are at least two versions of its origins. According to one story, it is a diminutive of ‘Shakespeare’, given to him by school friends and musicians in honour of his love of literature. Another story links it to his fondness for a particular Duke Ellington tune of the 1940s in which the trumpet features prominently — ‘Chocolate Shake’. Whichever version is true, the nickname alludes to his three great passions: music, English literature and the poetry of the Caribbean.

Early twentieth-century Kingstown was a mixture of poverty and aspiration. Unlike modern Kingstown with its concrete and glass business structures, the town centre then comprised both residences and places of work, often in the same building. In the 1930s only a few public streets had electric lights, and at night homes were lit by candles and oil lamps. The core of the capital was its three main streets. Bay Street and Back Street sandwiched Middle Street, in the lower section of which — called Lower Middle Street — the Keane family lived. Homes and businesses for the most part were small clapboard houses comprising ground and first floor. The family home was located in a lively artisanal area with open gutters running on both sides of the street. There were two blacksmiths nearby, as well as a small printery. From his upstairs bedroom window Shake could see into a nearby bakery, where the sweat poured off the backs of bakers kneading dough for their ovens. In the neighbourhood could be found two brass bands — the Keane family band and Cyril McIntosh’s Brass Band — as well as Melody Makers Steel Band, and further up the street Syncopators Steel Band. Black families, like the Keanes, could be classified as artisans aspiring to middle-class status, with homes slightly removed from...