![]()

1

The Birth of a Princess

Heard from Georgie that May had given birth to a little girl, both doing well. It is strange that this child should be born on dear Alice’s birthday, … the last was on the anniversary of her death.1

Queen Victoria’s diary, 25 April 1897

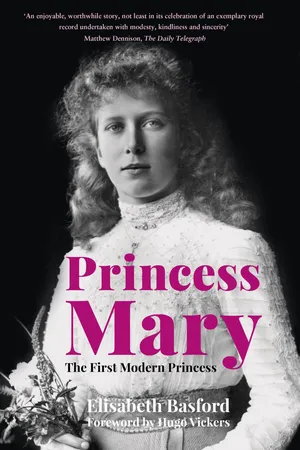

Princess Victoria Alexandra Alice Mary, known as Princess Mary, was born on 25 April 1897 at York Cottage on the Sandringham estate. She was the third child and only daughter of the then Duke and Duchess of York, who would later become George V and Queen Mary. Mary’s father, Prince George, Duke of York, was the only surviving son of the direct heir to the throne, Edward, the Prince of Wales, and his wife Alexandra, the Princess of Wales, who would in 1901 become King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra. The year of Mary’s birth was known more for the Jubilee celebrations of her great-grandmother, Queen Victoria, who by this time had been on the throne for a monumental sixty years. In 1897, the average life expectancy was a mere forty to forty-five years; thus Victoria had been monarch throughout most people’s lives. Princess Mary would witness no fewer than six monarchs in her lifetime.

The United Kingdom of 1897 was a far cry from the realm Victoria had inherited in 1837. In the same way that our modern Elizabethan age has witnessed vast sociological, cultural, scientific, technological and political changes, Victoria’s era was a time of radical advancements. The British Empire grew significantly during her reign and at its peak made up a quarter of the world’s population. The Diamond Jubilee public holiday of 22 June brought hundreds of thousands of people to witness the royal parade and service of thanksgiving. ‘The crowds were quite indescribable & their enthusiasm truly marvellous & deeply touching,’ Victoria recorded in her diary.2

When she acceded to the throne Victoria’s position was precarious, with only a handful of royal family members in the line of succession. However, by the end of her reign, Victoria was known as the ‘Grandmother of Europe’ having over thirty living adult grandchildren. She ensured not just the survival of her direct line but that of many European monarchies, including Norway, Denmark, Sweden and Spain. Even within her own family, Victoria was regarded ‘as a divinity of whom even her own family stood in awe’.3

Princess Mary’s mother was Princess Victoria Mary of Teck, known in the family as May. Princess May was the eldest child and only daughter of Princess Mary Adelaide of Cambridge and Francis, Duke of Teck. Francis was the child of a morganatic marriage (a marriage between two people of unequal social rank), meaning that he had no rights of succession to the Kingdom of Württemberg and was therefore a mere serene highness – though later HH The Duke of Teck. Finding a marriage partner for him had been difficult. Mary Adelaide of Cambridge was a granddaughter of George III, and for some time was in the direct line of succession. However, she also experienced similar difficulties in finding a marriage partner because of her colossal physical size. English historian and writer Janet Ross, who knew Mary Adelaide from their adolescence, recounted in her memoirs an occasion at a ball at Orleans House in Twickenham when the princess was dancing with the Comte de Paris: she ‘collided with me in the lancers and knocked me flat down on my back’.4 The American ambassador in London, Benjamin Moran, described her in 1857 (when she was 24) as being ‘very thick-set’, declaring her to weigh at least 250lb.5 Regardless of this, Mary Adelaide was known for her genial and ebullient nature. In 1883, Janet Ross and Mary Adelaide were reacquainted in Florence when both were living there to ease their financial difficulties. Janet remarked that ‘few women possess the charm of the Duchess of Teck; she took interest in everybody and her ringing laugh … would have made even a misanthrope smile’.6

Despite their arranged marriage, Mary Adelaide and Francis seemed to enjoy their life together, socialising and assisting in court events. The birth of their first child and only daughter, May, at Kensington Palace in 1867 appeared to complete their happiness. In journalist Clement Kinloch-Cooke’s authorised memoir of Mary Adelaide, we see an ideal picture of domesticity, with May’s father, Francis, unusually for a man in his position at this time, relishing the chance to enter the nursery in order to bathe his baby. In a letter to her close friend and royal courtier Lady Elizabeth Adeane (later Biddulph) on 6 March 1868, Mary Adelaide talks at length about her love for her baby: ‘She really is as sweet and engaging a child as you can wish to see … In a word, a model of a baby … “May” wins all hearts with her bright face and smile and pretty endearing ways.’7 Mary Adelaide and Francis went on to have three sons: Adolphus (1868), Francis (1870) and Alexander (1874).

Despite their seemingly perfect view of domestic bliss, Mary Adelaide’s propensity for partying and her generous charitable benevolence (she gave away a fifth of her income) meant that the £5,000 annual allowance from Queen Victoria was simply not enough for her to maintain her lifestyle. In 1883, the family had to move overseas for two years to escape their creditors. They hoped that by living off the benevolence of relatives they could in some way reduce their debts. They travelled to Italy, Germany and Austria, settling mainly in Florence. At first they went to the private Hotel Paoli on the Lungarno, frequently patronised by the English, and then to the Villa I Cedri at Bagno a Ripoli for the spring, a few miles outside Porta San Nicolo, to the south east of Florence. As one contemporary wrote:

The various circles of Florentine society vied with each other in their desire to make the Duchess of Teck’s stay pleasant and agreeable. It was of course, a great pleasure to the English residents to have Princess Mary (Adelaide) amongst them and her kindness of heart and personal charm endeared her to all who had the privilege of being presented to her.8

It was here that Mary Adelaide’s daughter, Princess May, developed an interest in Italian culture, spending much time visiting theatres, galleries, museums and churches. This would later inspire her appreciation of art and collecting, something May passed on to her daughter. There were daily visits to view the Old Masters in Florence such as Raphael, Van Dyck and Titian, along with lessons in singing, Italian and art.

The family returned to England in 1885 and made their home at White Lodge in Richmond. Princess Mary Adelaide was well known for her kindness towards her neighbours and the poor and was eager that her children should learn an empathy with those less fortunate. Kinloch-Cooke recalls in his biography of Mary Adelaide:

On one occasion, her Royal Highness was taking a stroll … and came across an old woman picking up sticks; the woman seemed tired and the day was cold. Very soon the Duchess was hard at work, pulling down the dead wood from the lower branches of the tree with her umbrella.9

This incident was far from unique for Mary Adelaide, who was the first royal to earn the nickname of ‘People’s Princess’ and took pride in assisting the poor. There are accounts of Mary Adelaide supporting neighbouring village fetes and bazaars, helping on stalls to boost sales. This was a trait that she was eager to pass on to her children, who learned the struggles of the lower classes by being taken to visit tenements and hovels. In addition, Mary Adelaide involved Princess May in the work of the Surrey Needlework Guild and the Royal Cambridge Asylum, as well as the Victoria Home for Invalid Children in Margate. Mary Adelaide was an early patron of such charities as Dr Barnardo’s, the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children and the St John Ambulance Association. A publication produced in 1893, The Gentlewoman’s Royal Record of the Wedding of Princess May and The Duke of York, describes Princess Mary Adelaide as ‘one of the most respected and beloved members of our Royal house, whose energy in charitable and philanthropic work deserves the nation’s gratitude’.10

In 1886, the young Princess May, who was described as ‘a remarkably attractive girl, rather silent, but with a look of quiet determination mixed with kindliness’,11 made her debut at court. It was no wonder that she was shy, with such an outspoken and gregarious mother. Yet this slightly aloof and dignified manner soon made her a firm favourite of Queen Victoria and she was singled out as a potential bride for Prince Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence and Avondale, known as Eddy, who was the eldest child and heir of Victoria’s heir, Edward, the Prince of Wales. In December 1891 their engagement was announced and as Mary Adelaide remarked in a letter to Lady Salisbury, ‘Eddy is radiant and looks it and our darling May is very happy, though at times her heart misgives her lest she may not be able fully to realise all the expectations centred in her.’12 Queen Victoria herself was pleased with the match and in her diary noted that ‘I was quite delighted. God bless them both. He seemed very pleased & satisfied, I am so thankful, as I had much wished for this marriage, thinking her so suitable.’13

If May had misgivings about the match, these were well founded. Prince Eddy had, in his grandmother’s words, lived something of a ‘dissipated life’.14 The match between his parents Bertie (Prince Edward) and Alix (Princess Alexandra) had come as something of a relief to Queen Victoria. Unlike his father, the saintly, moralistic, Prince Albert, Bertie enjoyed the company of women and living life’s pleasures to excess. Alix was a Danish princess and had been chosen as Bertie’s wife for her beauty and discretion. The marriage was relatively content, although Bertie continued to have affairs with many society beauties and actresses. In response, Alix gave all of her – at times, suffocating and possessive – love to her five children: two boys, Eddy and George, and three girls, Louise, Victoria and Maud.

Eddy inherited his mother’s tall, sinewy frame, yet Queen Victoria viewed Bertie and Alix’s children as fairy-like and puny, and this may be why so many later historians took to depicting Eddy as sickly and weak. A contemporary source states that ‘the child was not … either weakly or delicate … his general health, indeed, gave no cause for anxiety’.15

The life of Bertie and Alix and their Marlborough House set was filled with hunting and shooting parties, balls, race meetings and family gatherings and travel. Wanting to install some discipline into the young princes, in 1871 Queen Victoria appointed Canon John Neale-Dalton to tutor Eddy and George. At times, Dalton despaired at the lack of routine and stability that clearly prevented him from making progress with his charges. Dalton was ahead of his time in some ways, preferring to focus on how to learn rather than what to learn; by teaching his pupils life skills rather than cramming them with facts.16 By all accounts Dalton established an exacting curriculum for the two boys in his care, believing that they should receive a thorough grounding not just in academia, but also in physical pursuits, as well as the pastimes of country gentlemen such as hunting and shooting. Prince George was considered a good influence on his brother academically and so the princes remained together. Bertie was eager for his sons to escape the harsh regime of the schoolroom that he had been forced to endure under Prince Albert, and he wanted them to see for themselves the constantly expanding British Empire. With Dalton’s support, he managed to persuade his mother that the boys would benefit from a cadetship aboard HMS Britannia in Dartmouth. This was followed by three years aboard the Bacchante and, for Eddy, Trinity College Cambridge and later a stint with the Tenth Royal Hussars, the Prince of Wales’s regiment.

Although he was said to possess a benevolent nature, Eddy had scant regard for intellectualism or diligence. Rumours abounded of his predilection for chorus girls and partying. Queen Victoria thought marriage would be the only solution to curb the unstable and immoral prince. She invited Princess May and her family to Balmoral in November 1891, where she could see for herself if May would be a suitable wife for Eddy and found her ‘a dear charming girl and so sensible and unfrivolous’.17

Thus, on 3 December 1891, at Luton Hoo in Bedfordshire, Eddy proposed to May. ‘To my great surprise, Eddy proposed to me during the evening … Of course I said yes. We are both very happy.’18 The engagement was announced with preparations in place for a wedding the following February. Queen Victoria was so pleased with the engagement that on 12 December she took the happy couple to Prince Albert’s mausoleum for his ‘blessing’. For May, brought up to feel that she ...