![]()

PART 1

SOUTH SHIELDS

AND THE TYNE

Perchance a person South of York

May, whilst having varied talk,

(But not of fair Elysian fields)

Have heard of such a place as Shields.

Matthew Stainton, 18681

![]()

1

THE TRANSFORMATION

BEGINS

Robert Chapman’s life spanned most of the nineteenth century. Born in 1811 during the Napoleonic Wars, he would see profound social and economic changes before his death in 1894. At the time of his birth in South Shields on the south bank of the River Tyne where it meets the North Sea – then called the German Ocean – the town’s population had started to increase dramatically. From small beginnings of 11,000 at the time of the first national census in 1801, there was a 40 per cent increase by 1811, and by the end of the century the population had risen to 100,000.

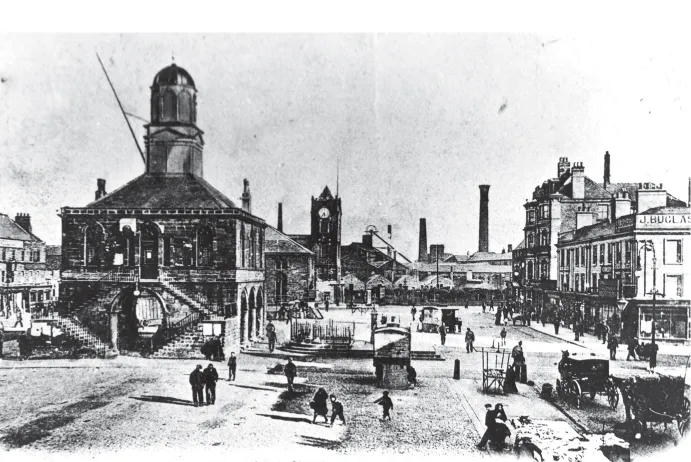

In the early years of the nineteenth century, South Shields was largely concentrated along the river, with small communities to the south in the nearby agricultural villages of Westoe and Harton. Its architectural pride and joy was the eighteenth-century Town Hall. Affectionately known as the ‘Pepper Box’, it was situated prominently in the middle of the Market Place, which was ‘chiefly occupied by private houses and the residences and offices of professional men’.1

They were fortunate enough to be comparatively well housed. However, for the vast majority of the population, living conditions ranged from the fairly primitive to the absolutely appalling. There was no gas or electricity supply and therefore no street lighting, little or no paving, no sewerage or efficient drainage system, and water supply was totally inadequate both in distribution – mostly by water carts – and in quality. This situation was both typical of expanding industrial towns and cities throughout Britain, and also disastrous for public health. To ameliorate conditions would require a strong economy, new municipal powers, and resolute political will.

1855 Ordnance Survey map of South Shields, published in 1862, by which time the population was around 35,000. (National Library of Scotland)

Sketch of the Market Place in the 1850s, showing the Old Town Hall of 1768, St Hilda’s Church (c. 1764), St Hilda’s Colliery (1825) and the chimneys of R. & W. Swinburn & Co.’s plate glass works. The Town Hall was affectionately known as the ‘Pepper Box’. (South Tyneside Libraries)

Shipbuilding, Coal and Industry

South Shields’ economy grew rapidly during Robert’s lifetime. The Napoleonic Wars had been good years for building sailing ships: by 1811 there were some 500 vessels totalling 100,000 tons registered to the town, which had a dozen shipbuilding yards and a larger number of docks.2 Operations were mostly on a modest scale, with the construction of wooden sailing ships requiring little complex equipment and employing relatively small workforces. Nevertheless, in total the industry employed around 1,000 shipwrights, one of whom was Robert’s father.

The Napoleonic Wars had also been productive years for the development of new and more powerful vessels. A year before Waterloo, in 1814, the Tyne celebrated its own first steamboat called, appropriately enough, the Tyne Steam Packet, which carried passengers between Newcastle, South Shields and North Shields. This new mode of transport would in due course make a significant contribution to the development of the river, especially since road communications between Newcastle and the coast were – and remained for another half century – exceptionally poor. The town clerk of South Shields, Thomas Salmon, recognised the revolutionary significance of the steamer’s maiden journey on 19 May 1814, recalling that ‘Being Ascension Day, it joined the procession of barges and boats, and was a great novelty. I was one of the multitude of wondering spectators, who witnessed its performances from Newcastle Bridge.’3 As it turned out, the passenger service was not a commercial success, and a new owner, Joseph Price from Gateshead, renamed her Perseverance a few years later and turned her very successfully into the first steam tug on the river.

The French may have been decisively defeated in 1815, but the immediate result was economic depression and distress, exacerbated by a currency panic. The Army reduced its numbers, and the Royal Navy reduced the size of its fleet, discharging seamen for whom there was no alternative employment. As Hodgson put it, ‘an immense body of seamen were thrown idle’,4 resulting in bitter strikes throughout the North East. In what were known as the ‘two Shields’ (North and South, reflecting the towns’ Tyneside locations), there were around 7,000 seamen and their demands were for increased wages and manning levels. Their strike committee was well organised and maintained strict discipline. Pickets prevented nearly all ships from sailing, and seamen who tried to set sail were taken out and paraded through the streets with ‘faces blackened and jackets turned’.5

Perseverance towing the brig Friends’ Adventure up river to Newcastle. Built in 1814, she became the first steam tug on the Tyne. Painting (formally entitled Seascape) by the American mariner and artist Frank Wildes Thompson (1836–1905). (Laing Art Gallery, Newcastle upon Tyne. © Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums/Bridgeman Images)

The ship owners appealed successfully for help from the Navy and the military. Cavalry were sent from Newcastle; a troop of dragoons was stationed on the Bank Top and marines on the sands; 600 special constables were sworn in; and two sloops of war stood by. The odds were stacked very heavily against the seamen, and in the event the strike collapsed in October 1815, just a month after it had started. Some 200 affected ships then put to sea. Nevertheless, three months later in January 1816, between 300 and 400 sailing vessels were still ‘laid up in Shields Harbour and unrigged owing to the badness of trade’.6

Economic conditions gradually improved, the new technology of steam started to spread widely, and expanding shipyards created jobs for unemployed seamen. In South Shields, Thomas Dunn Marshall had successfully developed steam tugs and in 1839 his yard launched the North East’s first iron ship, the Star. He then launched the SS Bedlington, an innovative iron-built, twin-screw train ferry, designed to carry loaded coal trucks in her hold. Although she was a commercial failure, the technological advance was significant, and in 1845 he built two iron-screw steamers (Hengist and Horsa) for owners in Bremen, followed by commissions for Hamburg owners, ‘the Germans thus showing their facility for assimilating new ideas quicker than their British competitors’.7

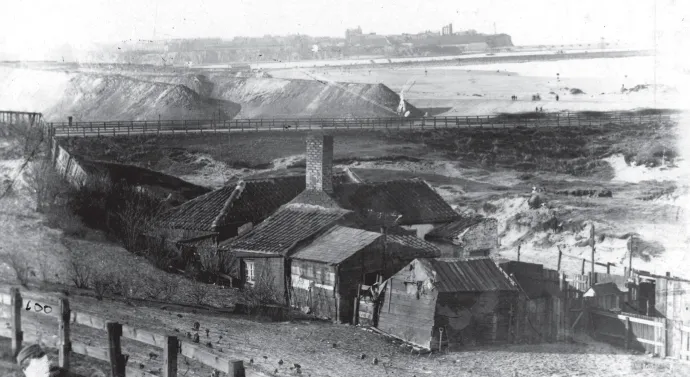

In 1844 there was another important technical innovation on the Tyne. John Coutts had built at his Walker shipyard, upstream on the north bank, a small sailing vessel of 271 tons, the Q.E.D. She was subsequently fitted with auxiliary engines made by Messrs Hawthorn at their Newcastle engine works. Q.E.D. (an abbreviation of the Latin Quod erat demonstrandum, or ‘what it was necessary to prove’) was not only a pioneering screw-propelled vessel, but, most importantly, she was the first ship to be built with a double bottom, enabling her to take in water to act as a ballast without spoiling the cargo holds. This was revolutionary, since the typical practice at the time was to use chalk as a ballast when empty vessels were returning to their home ports after delivering their cargoes. The banks of the Tyne were disfigured by huge heaps of chalk ballast. South Shields was no exception, with The Bents Ballast Hills alone covering an area of 30 acres.

By 1848 there were thirty-six shipbuilding yards on the Tyne, with steam power poised to replace sail in the decades ahead. Nevertheless, at this mid-century point, over 90 per cent of all vessels were sailing ships, and they continued to be built on a very substantial scale. When Robert Chapman became a ship owner in 1854, it was a sailing ship in which he invested. Its fortunes, and those of the mercantile sailing fleet as a whole, will be explored in the next chapter.

Chalk ballast unloaded from sailing ships at Cookson’s Quay was transported by railway to The Bents, whose unsightly ballast hills covered some 30 acres. In the background can be seen Tynemouth Priory. (South Tyneside Libraries)

The growth of Tyne shipbuilding in the first half of the nineteenth century was despite, rather than because of, the state of the river. South Shields and neighbouring downstream ports suffered from what can best be described as the curse of Newcastle, which through ‘ancient chartered privileges’ controlled the whole river, from its mouth to the west of the city. Newcastle had been an irresponsible conservator, and:

In fact the Tyne was a treacherous and inconvenient port with no defences at the entrance against gales which frequently strewed the Black Midden rocks with wrecks, and with a channel beset by shoals and obstructions. During the first half of the nineteenth century Newcastle took over £1 million in dues from shipping which used the port, but only about a third of that amount was spent in maintaining or improving the harbour.8

The brig Margaret at the mouth of the Tyne painted by the South Shields seafarer-turned-artist John Scott in 1849, when over 90 per cent of all vessels were still sailing ships. (South Shields Museum and Art Gallery. © Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums/Bridgeman Images)

This hugely disadvantageous situation – which had undoubtedly held back development in South Shields – started to be ameliorated in 1848, and was finally resolved in the early 1850s.

It was coal that fuelled the growth of the Tyne’s shipbuilding industry and economy. The increase in coal mining during the first half of the nineteenth century was by far the most important of all the industrial activities on Tyneside. It profited greatly from the existence of a ready market, especially in London, and from the ship-borne route to it. Transportation to ports was facilitated by the use of new waggon ways, while the increased use of steam power for pumping enabled deeper seams to be reached.9 New and deeper pits included the Templetown Pit, named after its owner Simon Temple, at the eastern end of Jarrow Slake in 1810, and the St Hilda’s pit in South Shields itself, owned by J. and R.W. Brandling, in 1822. Output almost doubled between 1831, when annual shipments from the Tyne were 2.2 million tons, to the early 1850s when they were around 4 million tons. Most of the coal continued to go to London, but exports responded to strongly increasing demand and started to be significant from 1831, when dues were reduced. They were abolished in 1845 for British-owned colliers (coal-carrying vessels). This export trade from the Tyne amounted to 161,000 tons in 1831 (7.3 per cent of total shipments), increasing sixfold to over 1 million tons in 1845 (30.6 per cent of all shipments).

Employment conditions and labour relations were woeful. In 1825 a Miners’ Union was formed, its publication, A Voice from the Coal Mine, heavily critical of poor ventilation and of the annual bond system with its low wages and potential for fines (‘a kind of legalised temporary serfdom’).10 A few years later the Union was incorporated into the Association of Colliers on the Rivers Tyne and Wear, which soon had some 4,000 members. In 1831 there was a miners’ strike, one of the key demands being a red...