![]()

2 Common Starling (Sturnus vulgaris Linnaeus, 1758)

Adrian J.F.K. Craig*

Department of Zoology and Entomology, Rhodes University, Grahamstown, 6139, South Africa

Citation: Craig, A.J.F.K. (2020) Common Starling (Sturnus vulgaris Linnaeus, 1758). In: Downs, C.T. and Hart, L.A. (eds) Invasive Birds: Global Trends and Impacts. CAB International, Wallingford, UK, pp. 9–24.

2.1 Common Names

Common Starling, European Starling, Eurasian Starling.

2.2 Nomenclature

Two independent molecular phylogenies of the Common Starling (Sturnus vulgaris Linnaeus, 1758) come to congruent conclusions, with the genus Sturnus restricted to the two species, S. vulgaris and S. unicolor, which form the sister group to other Asian starlings and mynas (Lovette et al., 2008; Zuccon et al., 2008).

2.3 Distribution

The natural breeding distribution of the Common Starling is from Iceland, the Faroe and Shetland Islands, the Azores and Canary Islands, the British Isles, Scandinavia, France and northern Spain, eastwards through Europe and Russia, to Lake Baikal, northern and eastern Kazakhstan, western Mongolia and western China (Xinjiang). Southern breeding limits are Turkey, Iraq, northern Iran, Turkmenistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Kashmir, eastern Uzbekistan and Tajikistan (Fig. 2.1). Migrants in the non-breeding season move south to North Africa, the Middle East, Arabia, Iraq, southern Iran, north-western India and north-eastern China (Craig and Feare, 2009). There is the occasional visitor to coastal China (Hebei), the Korean Peninsula, Japan, Sakhalin and Taiwan (Brazil, 2009).

Long (1981) stated that the Common Starling had been introduced successfully in the USA, Jamaica, South Africa, Australia, New Zealand and the Chatham Islands. It had then colonized the Bahamas, Bermuda, Canada, Alaska, Mexico, Fiji and many small islands off Australia and New Zealand. It was possibly introduced successfully to Vanuatu (New Hebrides) and Tonga but was apparently unsuccessful in Cuba, Venezuela and Ulan-Ude (USSR). Lever (2005) gave its naturalized range as the USA, Canada, Mexico, the West Indies, South Africa, Australia, Lord Howe Island, Norfolk Island, New Zealand and Chatham, Auckland, Campbell and Macquarie Islands, Kermadec Islands, Fiji, Tonga and possibly Vanuatu. He did not discuss failed introductions.

Common Starlings were apparently introduced to Argentina (Peris et al., 2005) and have since been recorded in neighbouring Uruguay (Mazzulla, 2013) and in Brazil (Cavitione e Silva et al., 2017). From South Africa, they have invaded adjoining areas of Namibia (Cunningham, 2016) and Lesotho (Kopij, 2001a).

2.4 Description

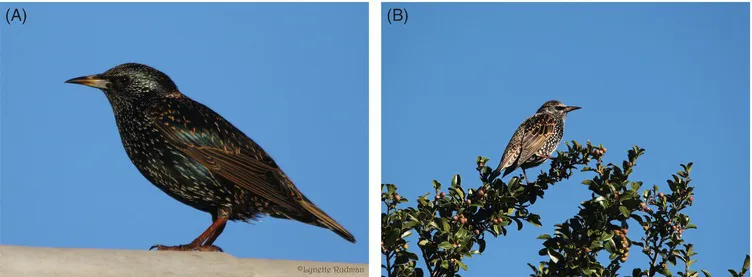

Male Common Starlings in fresh plumage have pale buff to whitish tips on all of the body feathers, producing a speckled appearance (Fig. 2.2A). The head is black with purplish-green iridescence, the wings and tail brown with some gloss, and there are narrow buff margins to the feathers. The chin and throat are blackish with some purple gloss, the breast and upper belly dark brown and glossed green, but they have purple gloss on the flanks. The belly and undertail coverts are matt brown with broad whitish margins. The iris is dark brown, the bill blackish and the legs brown. In the breeding season, the pale tips to most feathers have been lost, so that the male bird appears dark and glossy, with a strong purple gloss on the head and throat and a green gloss on the mantle, rump and breast; the elongated throat and upper breast feathers are frequently erected in display. The bill is a striking yellow colour, with the base steel blue, and the legs are pink (Craig and Feare, 2009).

Female Common Starling plumage is similar to that of the male, but the pale tips to the feathers are more persistent and the plumage is generally less glossy (Fig. 2.2B). The iris is dark brown, with a clear pale ring on either the inner or outer margin, while the bill of breeding birds is yellow with a pinkish base. Juvenile birds initially are grey-brown above, with buffy edges to the feathers of the wings and tail, a whitish throat, breast feathers that are whitish at the base with grey-brown tips, and dark shafts and tips to the belly feathers. The bill is dull brownish-black, the iris initially grey, becoming brown, and the legs pinkish-brown. During the moult to adult plumage, a very blotchy appearance is produced, and the head feathers are the last to be replaced (Craig and Feare, 2009).

Both adult and juvenile Common Starlings have a complete moult after the breeding season in both native and introduced populations, lasting for 80–100 days (Kessel, 1957; Cooper and Underhill, 1991; Rothery et al., 2001). There may be an incomplete or interrupted moult in migrant populations or late-breeding birds (Evans, 1986).

In all Common Starling populations, the sexes are most easily distinguished by the difference in colour at the base of the lower mandible during the breeding season (Kessel, 1951; Delvingt, 1961a; Wydoski, 1964; Coleman, 1973), with iris coloration the next most reliable criterion (Smith et al., 2005). The hackles (elongated feathers of the throat) are notably narrow and elongated in male birds but short and stubby in first-year females. However, first-year males and adult females cannot be separated on the appearance of these feathers (Kessel, 1951; Delvingt, 1961a; Coleman, 1973). Whereas the nestling sex ratio in the USA showed a slight female bias, the adult population was 59% male, suggesting higher female mortality (Davis, 1959). In the UK, Bradbury et al. (1997) also found a significant female bias in 108 broods containing 350 1-week-old chicks. Coulson (1960) calculated the mean annual mortality of British starlings as 53%, and suggested that differential mortality in the first year (39% for male birds, 70% for females) would explain the imbalance in the adult sex ratio. He noted that there was increased mortality during the breeding season, and ascribed this difference in first-year survival to the higher proportion of first-year females breeding. In the Czech Republic, first-year mortality was estimated at 68%, but by the third year, annual mortality was less than 40%, with some birds expected to survive for 15 years (Beklová, 1972). Longevity records reported were 16 years in the UK, 17 years in the USA and 21 years in Germany (Feare, 1984).

In South Africa, white rectrices were noted in 28 subadult Common Starlings, but only once in an adult (Skead, 2006). It is not clear whether these feathers are replaced by normal-coloured rectrices at the first complete moult or whether these birds suffer higher mortality at an early stage; white rectrices are present in some subadults but extremely rare in adult birds in the native range (C.J. Feare, personal communication). There is a record of three albino nestlings in England, with a normal adult in attendance at the nest (Garner, 1997).

There is some seasonal variation in Common Starling body mass, but male birds are consistently heavier on average than females (Europe: Eble, 1963; South Africa: Cooper and Underhill, 1991; New Zealand: Coleman and Robson, 1975).

Whereas 13 subspecies of Common Starling are recognized over its breeding range, distinguished by plumage coloration and other morphological differences, the introduced populations show only minor changes in size in New Zealand (Ross and Baker, 1982) and in wing morphology in the USA (Bitton and Graham, 2015) and Australia (Cardilini et al., 2016; Phair et al., 2018), probably reflecting random local variations in small, isolated populations. Little genetic variation was found within the populations in New Zealand (Ross, 1983), South Africa (Phair et al., 2018) and the USA (Cabe, 1993), but some genetic differentiation was evident in Australia (Phair et al., 2018).

2.5 Diet

The Common Starling is essentially omnivorous and opportunistic in food selection, feeding on a wide variety of plant and animal material. Vertebrate food items include small reptiles and amphibians and the eggs of other birds, while plant foods include fruit and seeds of a wide range of wild and cultivated plant species, such as yew (Taxus spp.), oak (Quercus spp.), apple (Malus spp.), pear (Pyrus spp.), cherry and plum (Prunus spp.), rowan (Sorbus spp.), elder (Sambucus spp.), nightshade (Solanum spp.), bryony (Bryonia spp.), buckthorn (Hippophae spp.), olive (Olea spp.), grape (Vitus spp.) and grains such as sorghum, wheat, oats, barley, millet and maize; nectar may also be taken from flowers (e.g. Aloe and Erythrina spp.). Often, the bulk of the food is insects, both adults and larvae, such as craneflies (Tipulidae), butterflies and moths (Lepi...