- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

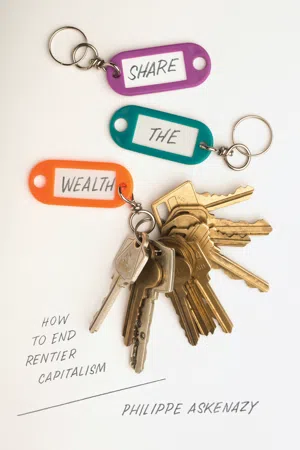

About this book

How can we reduce inequalities? How can we make work get better recognition and better pay?

Philippe Askenazy in this new book shows that the current share of wealth is far from natural; it results from rising rents and their capture by the actors best endowed in the economic game. In this race for rents, the world of work is the big loser: while many workers feed capital rents by increased productivity and worsened working conditions, they are stigmatized as unproductive and their earnings stagnate. By proposing a new description of the capital-work relationship, calling for a remobilization of the world of work, and particularly poorly paid employees, Askenazy shows that there is a more radical alternative to neoliberalism beyond simply redistribution.

Philippe Askenazy in this new book shows that the current share of wealth is far from natural; it results from rising rents and their capture by the actors best endowed in the economic game. In this race for rents, the world of work is the big loser: while many workers feed capital rents by increased productivity and worsened working conditions, they are stigmatized as unproductive and their earnings stagnate. By proposing a new description of the capital-work relationship, calling for a remobilization of the world of work, and particularly poorly paid employees, Askenazy shows that there is a more radical alternative to neoliberalism beyond simply redistribution.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Share the Wealth by Philippe Askenazy in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Political Economy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Fascination with the 1 Per Cent

In the closing years of the twentieth century, capitalism became faceless. Worker and consumer alike found themselves confronting elusive but domineering spectres: those of finance and the multinationals, from vulture funds to Monsanto. Capitalists had disappeared behind acronyms. And the heads of small or medium-sized enterprises were reduced to the status of subcontractors exploited by these powers.

The only capitalists still possessing a face, from the American Bill Gates (Microsoft) via the Italian Sergio Marchionne (Ferrari) or the Korean Lee family (Samsung) to the French Pinault dynasty (Gucci), were characterized as brilliant entrepreneurs or inventors; their success was construed exclusively as the consecration of their qualities. Furthermore, these men (rarely women) were patrons of prominent cultural and social causes. Wealth was not taboo because it was an engine for the most innovative, and would trickle down to the rest of society.

The 1 Per Cent as the New Face of Capitalism

Little by little, a change occurred at the start of the twenty-first century. Capitalism once again had a face: the wealthiest, the ‘1 per cent’, even the super-rich – the billionaires who feature on the Forbes list. Materially replete, the only thing most of these wealthy rentiers lacked was notoriety. Accordingly, some of them did all they could to emerge from obscurity. Thus, we discovered Paris Hilton, the immensely rich inheritor of the Hilton hotel chain. After starting out as a mannequin in charity parades, she burst onto the media scene by co-hosting a US reality TV show. A veritable popular phenomenon, she fuels magazines (female and male!), where we learn that her feet are size eleven. Meanwhile, the public experiences a mixture of fascination and discomfort with these idle lives where jet-setters, toy boys and toy girls bump into one another. A whole bestiary populates a parallel universe.

The ambivalent feelings aroused by this universe are even conveyed by children’s games. In the brilliant introduction to the book he has devoted to the rich,1 Thierry Pech unpacks the mutation of Monopoly. In twentieth-century Monopoly, the wealthy man lived what on the whole was an ‘ordinary’ life: he paid hospital charges, bought a house, and even paid taxes on his properties. In today’s Monopoly, he buys an island or a whole town, celebrates his birthday on a privatized Australian beach, or receives a tax rebate of 500,000 euros, pounds or dollars.

And then, whether it is the spectacle of the Bettencourt family (L’Oréal) in France, the nepotism of the Korean chaebols, or the multiple tax-avoidance schemes that cater to American fortunes, the wealthy end up becoming tiresome and shocking.

Meanwhile, academic works on the wealthy proliferate and circulate widely. For example, in France the works of the sociologist couple Monique and Michel Pinçon-Charlot, such as Ghettos du Gotha, have met with great success. In this context, a group of economists has put some figures on this particular face of capital. Sir Anthony Atkinson, British pioneer of studies of inequality, has been joined by two French figures, Emmanuel Saez and Thomas Piketty.1 Using fiscal sources, they have constructed a very broad longitudinal body of data over the long term, describing the share of total national income taken by the highest incomes. Their data reveal the capture of an increasing share of national income by a very small minority: not the wealthiest 10 per cent, but essentially the 1 per cent. This phenomenon is global, but is more marked in the Anglophone countries – especially the United States, where the share of the 1 per cent returned in the 2010s to its level at the start of the twentieth century, when it received more than 20 per cent of national income, as against 15 per cent in the UK and a little less than 10 per cent in France and Japan.

The value of large estates has also grown much more rapidly than global GDP. Moreover, the higher one goes – reaching one-thousandth of the wealthiest and then one-millionth – the more income and wealth have advanced. Income and wealth are in fact closely linked, a significant portion of income now being derived from wealth, not from work.

These analyses of the 1 per cent, as well as those by Joseph Stiglitz, directly inspired the slogan of Occupy Wall Street: ‘We are the 99 per cent.’ European movements of indignados – while more influenced by Indignez-vous!, by another Frenchman, Stéphane Hessel – have also deployed the spectre of the 1 per cent in their arguments.

The enormous global success in 2014 of Thomas Piketty’s book, Capital in the Twenty-First Century,2 tended to confirm a switch from fascination to denunciation. Among radicals and a number of American liberals, it held out hope for a wake-up call that might lead to a tax revolution. However, less than three years later, Donald Trump, a billionaire – epitomizing the images of the self-made man and the reality TV star to be found among the 1 per cent – was installed in the White House, implementing a programme at the antipodes of Piketty’s prescriptions. How are we to interpret such a disappointment?

The Theory of the 1 Per Cent Exploited by the 0.1 Per Cent

The resonance of Piketty’s book in 2014, in the United States and then elsewhere, was a cause of much surprise in France. On its appearance in French in 2013, it met with only moderate success in the bookshops. In the United States, Occupy Wall Street was already in its third year of existence when the book came out. Above all, it is a thick academic tome. To understand the enthusiasm it generated, we must return to the various stages of the launch of the US edition. We shall see that the relevance of this far exceeds the secrets of creating a bestseller; we are dealing, rather, with the construction of the dominant economic and political ideas.

It was Paul Krugman, winner of the Bank of Sweden prize in memory of Alfred Nobel and one of the most widely read commentators in the United States, who fired the opening salvos upon the release of the English-language version. In his column, he proclaimed that the book furnished irrefutable proof of the excesses of US capitalism and the appetites of the wealthiest. This column was to trigger a coordinated riposte, frequently in bad faith – even violent – from (neo)conservative circles. This prompted, in turn, a counter-offensive from radical intellectuals and the media. Since the book was not distributed by a mass-market publisher, buyers had to go via the internet in very large numbers to purchase it. It thus became a bestseller on Amazon.com – which accelerated its sales, and hence the media loop. The same scenario of frontal assaults and counter-offensives was repeated upon its publication in Britain. The Financial Times, the pre-eminent organ of the world of finance, even claimed on its front page to have detected manipulation of the data. In every country where the book was translated, it was the same story.

The seeming naivety of neoliberals and neoconservatives is astounding. By attacking the book so heavily, and the author sometimes so directly, they ensured its promotion, and thereby maximized the audience for the ideas it was defending. How could the same conservatives who for decades had proved adept at manipulating opinion in the economic and geopolitical arenas alike have made such a mistake?

A return to France suggests a different interpretation. The Hexagon has its own share of neoliberals (and even neocons). Private discussions with some of them evinced no particular hostility towards the identification of the 1 per cent as the central sign of inequality. On the contrary, they seemed comfortable enough with it. In fact, that a book which was social-democratic in inspiration should become central, and that its author could be characterized as the new Karl Marx, was experienced as a lesser evil compared with the risk of radical, even revolutionary, movements in the context of the Socialist Party’s anticipated meltdown. Similarly, it is very reassuring to have a Pope Francis resurrecting within the Church (which maintains its reactionary social teachings) the ecological question and the condemnation of Mammon long consigned to ‘leftists’.

How is it that most analyses of the 1 per cent are not unduly dangerous for capital? In short, they are not conducive to challenging capitalism itself, whether in a Marxist idiom – ‘alienation of the workers’ – or for its environmental ravages. They displace contestation of capitalism onto the rich and their apparent egotism. Better still (and doubtless this is the key point) they take for granted, or confirm, the natural character of the primary allocation of income – that is, income distribution prior to taxation and redistribution between workers and between capital and labour. Let us consider two arguments that structure current debates.

The most-cited works on the stratospheric and significantly increasing incomes of senior executives are those of Xavier Gabaix and Augustin Landier.1 They rationalize the distribution of CEOs’ incomes, presented as proportional to the sizes of their enterprises. Hierarchy framed as meritocratic, with the ‘best’ at the head of the largest firms. According to their estimations, placing at the head of the 250th enterprise the CEO of the first would guarantee it a higher profit (of the order of 10 per cent). Although this gradient is very shallow, the sums at stake for shareholders are such that it is natural for them to pay salaries to attract the best. However, this argument is decidedly weak. In fact, even if we accept their results, the authors ignore the effects of pronounced social reproduction, in which the personnel involved are drawn from the same caste of graduates from a few elite universities. The hierarchy they observe exists only within the tiny class of the CEOs in post. And nothing proves that the manager “n-4” of the same enterprises would not obtain better results if they were made CEOs.

The Meaning of Equations

The ‘first basic law of capitalism’ formulated by Thomas Piketty derives from the same logic of naturalization. This ‘law’ is above all a computable, hence exact, equation: the share of the income of capital α is equal to the product of the average rate of return of capital r and the capital/income relationship, denoted as β: α = r × β.

Marxist theory writes the same computable equation differently: r = α/β.

Seemingly minor, this difference is in fact major. In the Marxist interpretation in Capital, the share α is the translation of capital’s capacity to appropriate rents. The return r can be constant, because β increases when α grows. In effect, β is not a physical measure of capital, but the monetary value of assets that grows a priori when investments yield greater profits. Taken to an extreme, this reading embodies the communist idea of socialization of the means of production. In the context of a market economy, it identifies levers for a fairer society: labour movements, class struggle, or the social and cooperative economy.

In Capital in the Twenty-First Century, the return on capital r is regarded as largely given: it is the translation of natural technological parameters, like the marginal productivity of capital and the replacement of labour by capital. Furthermore, according to Piketty, this return is relatively constant over the long term. The weight of profit α is thus the simple outcome of the accumulation of capital.

In this framework, primary inequalities can decrease only when the rate of economic growth exceeds the return on capital – something observed in the major countries of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) only during the decades following the Second World War.

Given natural primary inequalities, and faced with weak or moderate growth, the reduction of inequality has to be conceived at a secondary level – that is, it must essentially take the form of redistribution, in the form of a highly progressive tax system of the ‘Robin Hood’ variety. This is the core of Piketty’s book, which for example evokes a hypothetical global tax on large estates. It is also that of Atkinson,1 who proposed operational strategies for the pre-Brexit UK. This guiding principle has long been found in the programmes of the main European social-democratic parties as well as the US Democratic Party.

Redistribution at an Impasse

Yet this efflorescence of works hardly perturbs capital, neoliberals and neoconservatives. On both sides of the Atlantic, analyses – for example, by the US economist Richard Freeman and the French sociologists Michel Pinçon and Monique Pinçon-Charlot – say the same thing. On the one hand, the way US politics is financed ensures a pragmatic majority within the Democratic Party; on the other, ‘the series of renunciations must be situated within the long history of minor and major betrayals by a governmental socialism that long ago chose sides’.1 In fact, when social democrats were in power, as in France from 2012 to 2017, they did not implement the solutions contained in their programmes and even adopted the insistent discourse of tax reductions. They made do with adjustments that did not reverse the pattern of inequalities. The presidential terms of the Democrat Obama proceeded from the same logic, and had a qualitatively similar outcome.

This pragmatism is all the more entrenched in that reinvigorating redistributive systems would require numerous technical obstacles to be surmounted. The retreat of the state as an economic actor locks it into a strategy resorting to tax incentives to try, in spite of everything, to construct an industrial policy; tax havens exist in all countries. Largely ineffective, these incentives open up the game of tax optimization that enables the most affluent and large numbers of big firms to determine the levels of tax they are prepared to pay.2 The globalization of firms, fortunes and incomes, combined with tax competition between states, further enables the most powerful to choose the level of their tax burden.

In addition, the idea of a division of the population into 1 per cent versus 99 per cent is, in part, misleading. It corresponds to a snapshot on a given date. During their life-cycle, a voter has a probability much higher than 1 per cent of one day figuring among the 1 per cent of highest incomes and fortunes. If she expects or hopes to enter this first centile in the future, she will be likely to support proposals for low taxation of the best-off.

At the other extreme of income distribution, support for social welfare and redistribution is far from automatic. The skill deployed by conservative forces to make the question of immigration the key political issue is not only electoral. As various works show,1 the myth of the immigrant exploiting the welfare system2 fuels hostility among ‘popular strata’ to instruments that largely benefit them. As for electorates whose majority comprises small property owners, they are worried by taxes on estates. I shall return to this.

Furthermore, the fear of being stigmatized as living on benefits is so marked that the take-up of various social benefits is sometimes low, as in France with the Revenu de solidarité active or in Germany with the Sozialhilfe. Poverty porn in advanced societies orchestrates this stigmatization, often inadvertently but sometimes deliberately; the British TV series Benefits Street was an example of this. In documentary mode, it claimed to portray everyday life in areas where virtually the whole population lived on social minima. It earned Channel 4 record audiences, thanks no doubt to its voyeuristic character.3

In this regard, the electoral success of a Donald Trump, with his promise to combine a revival of working-class America with cuts in social programmes, seems almost inevitable.

The Cynics of Inequality

A glance at the activity of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has the effect of persuading us of the cynicism of neoliberalism’s promoters. The new leitmotif is ‘inclusive growth’. After...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1. Fascination with the 1 Per Cent

- 2. Capitalism Unbound

- 3. Propertarianism

- 4. Winner Corporations

- 5. ‘Less-Skilled’ Effort

- 6. Remobilizing Labour

- 7. Weakening the Hand of Property

- Conclusion: Beyond Pragmatism

- Notes

- Index