![]()

Gardens by the Bay, Singapore. Opened in 2012, the 54-hectare garden now attracts 50 million visitors yearly and is a key part of making Singapore the “City in a Garden”. Photo courtesy of Pascal Garbe and used with permission.

1

Introduction: Philosophy of New Directions in Garden Tourism

In 1954, the marketing guru Peter Drucker said:

If we want to know what a business is we have to start with its purpose ... There is only one valid definition of business purpose: to create a customer. It is the customer who determines what a business is. For it is the customer, and he (sic) alone, who through being willing to pay for a good or service, convert’s economic resources into wealth, things into goods. What a business thinks it produces is not of the first importance – especially not to the future of the business and to its success. What the customer thinks he or she is buying, what he or she considers ‘values’, is decisive. Because it is its purpose to create a customer, any business enterprise has two – and only these two – basic functions: marketing and innovation.

(Drucker, 1954)

That paragraph summarizes, in a nutshell, what this book is all about. In 2013, the first edition of the book Garden Tourism was published. It essentially put between two covers what the history, significance, nature, and dimensions of garden tourism were. It was the first book to deal entirely with garden tourism, but it encapsulated why garden tourism was such an important part of both the tourism industry and the botanical world of gardens and garden visitation. It has now been 7 years since that first edition. In those 7 years garden tourism has grown remarkably, some would say exploded, and the innovations and marketing so fundamental to Peter Drucker, 60 years ago, have been realized, such that today garden tourism may be the most important and largest sector of contemporary outdoor leisure.1 For this second edition, it would have been easy and desirable to just update progress in the field of garden tourism since 2013 but that would have left unaddressed the vast strides that have occurred in garden tourism in the past 7 years. It is the aim of this book to go beyond the baseline description of garden tourism developed in the first edition and examine the innovations and marketing in garden tourism that have made it what it is today.

The Current State of Research in Garden Tourism

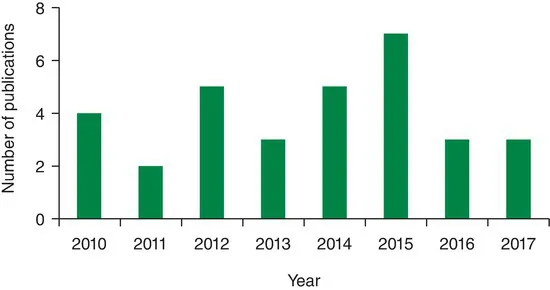

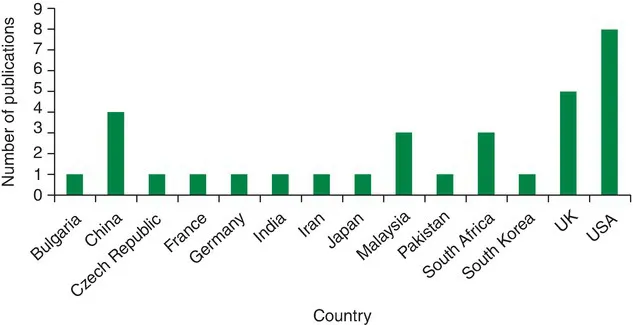

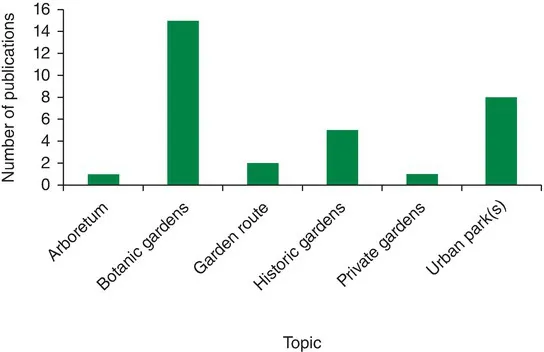

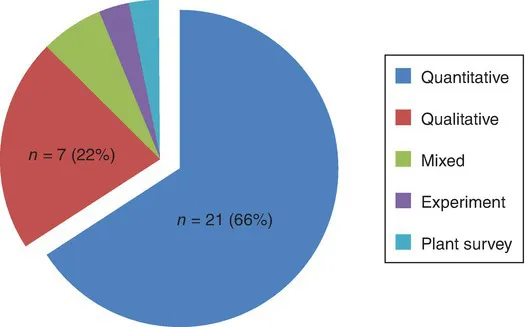

While evidence exists that garden visiting is now one of the most important sectors of the leisure industry, it is lamentable that the academic research community has not embraced garden tourism. Indeed, in a review of the first edition, the noted tourism researcher Kevin Markwell (2014) commented “that there has been surprisingly little scholarly research conducted on garden tourism”. In May 2017, as part of a Kew Gardens’ conference on garden tourism, one of the few researchers over the years to recognize and address garden tourism undertook a content analysis of all English-language, peer-reviewed journals and articles with the words garden plus visitor, tourist, or tourism in the abstract (Fox, 2017a). She found 32 articles in 23 different journals (Fig. 1.1). The majority of articles were published in the USA (8), the UK (5), and China (4). Eleven other countries were represented in the literature (Fig. 1.2). Most (14) discussed botanic gardens, followed by urban parks and gardens (8) and some historic gardens (4) (Fig. 1.3). Most (66%) were quantitative in methodology and 22% were qualitative in nature (Fig. 1.4). The most topical areas were attracting visitors (Lee et al., 2010; Byun and Jang, 2015), management of the garden (Banks, 2015), and new technologies (Pérez-Sanagustín et al., 2016). In short, for the most popular contemporary leisure activity in the world, the attention of researchers and practitioners has been lamentable. In the first edition, it was suggested that garden tourism presents itself as a fruitful (and enjoyable) area of research. Sadly, in the years since, that challenge has not been taken up. As a result, readers will find, as material in this book, much that is a narrative of what has occurred in the years since 2013 rather than new academic insight and conclusions. Much of the narrative is based on individual gardens’ own research or perspective; little is external. This is an area that must change if a more complete story of the tourism industry is to be told. To that end other areas neglected in the first edition have been addressed.

Fig. 1.1. Number of published articles on garden tourism, 2010–2017. Adapted from Fox (2017a).

Fig. 1.2. Source of published articles on garden tourism, 2010–2017. Adapted from Fox (2017a).

Fig. 1.3. Topic of published articles on garden tourism, 2010–2017. Adapted from Fox (2017a).

Fig. 1.4. Type of research conducted in published articles on garden tourism, 2010–2017. Adapted from Fox (2017a).

Markwell also pointed out in his perceptive review that:

Readers will not find engagement with debates concerning authenticity, commodification, embodiment, emotions or the experience economy, nor does the book intersect with the literature on ‘natures’, constructed or otherwise. Yet gardens are surely one of the best examples of nature–culture hybrids. In this regard, Benfield misses an opportunity to examine how garden tourism provides opportunities for our understandings of the relationships between nature and culture to be deepened and, perhaps, challenged. Certainly, he does examine relationships between garden tourism and cultural tourism (29) and art (54) but he does not extend this examination into an engagement with deeper philosophical or theoretical concerns. I was also surprised at the lack of an extended discussion of gardens as significant elements of destination identity and branding. Again, I think there were opportunities to explore, in much more depth, the role of large public or commercially operated gardens in the creation of a destination brand or image for certain destinations.

(Markwell, 2014)

These were valid observations and this new edition of the book addresses them in part; only in part because, as was noted earlier, there has been so little published in the garden tourism literature in areas such as authenticity, commodification, and branding. In summary, this book will update the reader on progress in garden tourism by introducing new gardens, new audiences, new strategies, new initiatives, and new programs that in total over the past 7 years are making garden tourism the dominant mode of contemporary outdoor tourism.

Innovation and Marketing; The Structure of the Book

In the following chapter, a selected appraisal of garden tourism around the world in terms of garden numbers, number of visitors, and growth is given. It updates numbers and development of garden tourism and contains a brief appraisal of how garden tourism has grown, or not grown, in the prior 5 years.

Chapter 3 examines new directions in garden tourism (innovation) by selecting seven major product development and marketing innovations that have characterized gardens in the preceding 7 years. They are:

• gardens and wildlife;

• art and gardens;

• gardens and music;

• Levy walk analysis and gardens;

• plant societies and gardens;

• sensory experiences at gardens; and

• garden branding.

Chapter 4 examines new audiences and particularly the greater sophistication in market segmentation since 2013. The demographer David Foot claims that demographics explains “two thirds of everything”; hence changing demographics, 7 years on, is examined and particularly the growing numbers of, and interest in, the so-called “Millennials”. If demography explains two-thirds of everything then perhaps the field of psychographics covers all or part of the remaining third. Increasingly gardens are using psychographic studies to segment their audiences and examples will be drawn from Kew and the National Trust in the UK, and Newfields in Indianapolis, USA. This chapter will also introduce two other market research developments in gardens that may be used for segmentation bases. These are Claritas and geofencing, both of which are inherently geographical in their base of analysis.

Chapter 5 examines the new media landscape of communities (blogging and podcasting), platforms, and social media, a phenomenon that has exploded in the past 7 years such that Al Reis2 says “in marketing today there is social media and everything else”.

Chapter 6 explores the deep psychological draw and attraction of flowers, gardens, and gardening, first examined under the study of semiotics by John Urry in the late 20th century and which is still little examined as a cause or motivation for garden visiting.

Chapter 7 is dedicated to the study of garden-related events. Getz and Page (2016a,b) chart the phenomenal rise of event tourism and the concurrent rise in academic research. More specifically, Connell et al. (2015) highlight the use of events to fill gaps left in off-peak times and seasons and it is in this area that gardens have developed significant programs and events to make them more financially stable and educationally viable.

Chapter 8 goes into more depth than the previous edition on the economics of garden tourism because significantly more gardens are examining the economic benefits of their gardens. As important, the chapter also highlights the environmental, health, and social benefits of gardens in an era of environmental sustainability, and social justice.

Chapter 9 focuses on the urban environment in which garden tourism takes place. Many gardens are now characterized by meaningful, visual, and impactful outreach into both the surrounding communities and the city in which they are located. In some cases, the crossover into streetscaping and events have become significant generators of urban garden tourism. As a result, one of the examples this book uses – the Chelsea Fringe Festival in London and elsewhere – was featured in Chapter 7.

Chapter 10 isolates historic garden tourism and the current management and development of historic gardens as opposed to the purely historic nature of gardens developed in the previous edition. Here the focus is on landscape, which is a more holistic approach to historic sites, and marks innovation in historic garden tourism.

In Chapter 11, the future of garden tourism is examined. Moskwa and Crilley (2012) indicate that botanic gardens have multiple roles but principally education, environmental, and recreation, a...