![]()

![]()

‘Media’, intoned Marshall McLuhan in 1964, are ‘extensions’ (1998: 48). Circling the globe in a benevolent electronic web, television, radio, film and the print press enabled men and women to stretch their senses, to reach out to one another and to become equal citizens in a global village, he explained. Even as McLuhan spoke, the hipsters and artists of New York and San Francisco were building prototypes of the world he described: new multimedia environments in which they would soon conduct what amounted to tribal rites. Within little more than a year, coloured lights, multiscreen slide shows and walls of amplified sound surrounded dance floors and performance art spaces on both coasts and in more than a few Midwestern capitals as well. For McLuhan, as for much of the emerging American counterculture, to be ringed by media was to enter a state of ecstatic interconnection. At first to dance and then later to gather at Be-Ins and rock concerts was to open oneself to a new way of being – personal, authentic, collective and egalitarian.

But where did this vision come from? Only 25 years earlier, most American analysts were convinced that mass media tended to produce authoritarian people and totalitarian societies. Accounts of just how they did this varied. Some argued that mediated images and sounds slipped into the psyche through the senses, stirred the newly discovered depths of the Freudian unconscious and left audiences unable to reason. Others claimed that the one-to-many broadcasting structure that defined mass media required audiences to turn their collective attention toward a single source of communication and so to partake of authoritarian mass psychology. In the late 1930s, if anyone doubted the power of mass media to remake society, they only needed to turn to Germany. How could the moustachioed madman Adolf Hitler have taken control of one of the most culturally sophisticated nations in Europe, many wondered, if he had not hypnotized his audiences through the microphone and the silver screen?

In the months leading up to America’s entry into the Second World War, Hitler’s success haunted American intellectuals, artists and government officials. Key figures in each of these communities hoped to help exhort their fellow citizens to come together and confront the growing fascist menace. But how could they do that, they wondered, if mass media tended to turn the psyches of their audiences in authoritarian directions? Was there a mode of communication that could produce more democratic individuals? A more democratic polity? And for that matter, what was a democratic person?

Back to the Late 1930s

It was the answers to these questions that ultimately produced the ecstatic multimedia environments of the 1960s and through them, much of the multimedia culture we inhabit today. To see how, we need to return to the late 1930s and early 1940s and to track the entwining of two distinct social worlds: one of American anthropologists, psychologists and sociologists, and the other of refugee Bauhaus artists. At the start of the Second World War, members of the first community believed that the political stance of a nation reflected the psychological condition of its people. That is, fascist Germany represented not only the triumph of Hitler’s party, but of what would later be called the ‘authoritarian personality’ (Adorno 1950). In 1941, more than 50 of America’s leading social scientists and journalists gathered in Manhattan to promulgate a democratic alternative to that personality as members of the newly formed Committee for National Morale. Though largely forgotten today, the committee was very influential in its time. Its members published widely in the popular press and advised numerous government officials, including President Roosevelt.

Across the 1930s, committee members such as anthropologists Margaret Mead and Gregory Bateson and psychologist Gordon Allport worked to show how culture shaped the development of the psyche, particularly through the process of interpersonal communication. In the early years of the war, they turned those understandings into prescriptions for bolstering American morale. First, they defined the ‘democratic personality’ as a highly individuated, rational and empathetic mindset, committed to racial and religious diversity, and so able to collaborate with others while retaining its individuality (Allport 1942: 3–18; see also Herman 1995: 48–53). Second, they argued that the future of America’s war effort depended on sustaining that form of character and the voluntary, non-authoritarian unity it made possible (see, for instance, Mead 1942). In their view, both individual character and national culture came into being via the process of communication. Since mass media prevented precisely the sorts of encounters with multiple types of people and multiple points of view that made America and Americans strong, the shoring up of the democratic personality would require the development of new, democratic modes of communication.

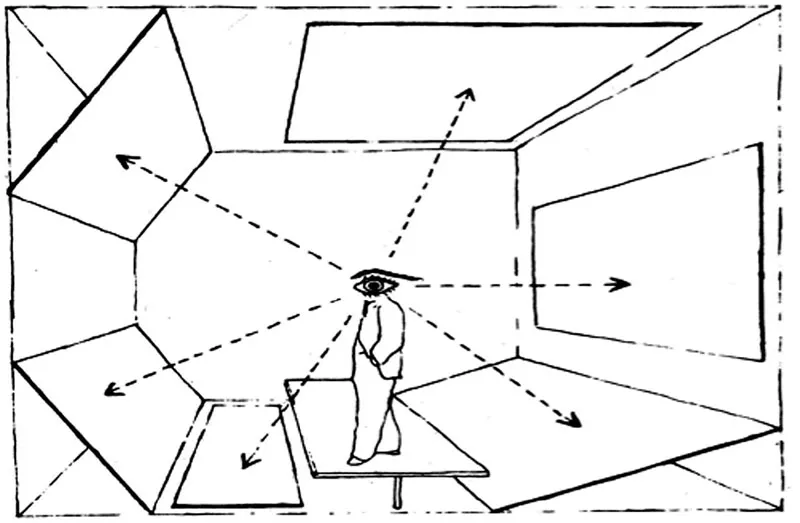

For that reason, members and friends of the committee advocated a turn away from single-source mass media and toward multi-image, multi-sound-source media environments – systems that I will call surrounds. They could not build these systems themselves. With a few exceptions, they were writers, not media-makers. But they knew people who could: the refugee artists of the Bauhaus. Since the early 1930s, Bauhaus stalwarts such as architect Walter Gropius and multimedia artists László Moholy-Nagy and Herbert Bayer had fled Nazi Germany and settled in New York, Chicago and other centres of American intellectual life. They brought with them highly developed theories of multiscreen display and immersive theatre. They also brought with them the notion that media art should help integrate the senses and so produce what they called a ‘New Man’, a person whose psyche remained whole even under the potentially fracturing assault of everyday life in industrial society. As the Second World War got under way, they repurposed their environmental, multimedia techniques for the production of a new ‘New Man’ – the democratic American citizen. By 1942, Herbert Bayer was collaborating with American photographer Edward Steichen to create complex multi-image propaganda displays at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. And László Moholy-Nagy was working with composer John Cage, alerting him to both the environmental and industrial-therapeutic aims of Bauhaus art and to the ways such things might be used in wartime America.

In the Wake of the Second World War

Under the pressures of the Second World War, the refugee artists of the Bauhaus and the intellectuals of the Committee for National Morale created the pro-democratic surround and the networks of ideas and people that would sustain it in the years ahead. In the late 1940s, as the chill of the Cold War began to creep across America and Europe, communism replaced fascism as the source of totalitarian threat. But the wartime consensus persisted: intellectuals, artists and many policy-makers continued to agree that political systems were manifestations, mirrors even, of the dominant psychological structures of individual citizens. The surrounds developed during the Second World War lived on as models – for new exhibitions, new works of art, new modes of environmental media and, ultimately, new patterns of democratic practice. Through them, the ideals of democratic psychology and democratic polity articulated by wartime social scientists remained available, not only as words in texts, but as invitations to embodied action. Anthropologists and artists gathered at places like Black Mountain College, where they worked to train a new generation of American artists in the multidisciplinary, progressive political ideals that infused wartime campaigns for democratic morale. Likewise, at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, Edward Steichen transformed Herbert Bayer’s wartime exhibition design into what almost certainly remains the most widely viewed photography exhibition of all time, The Family of Man. The exhibition featured 503 photographs of men, women and children from around the world, made by 273 international photographers. At a time when America was riven with racism and when the nuclear threat dominated international relations, the show was designed to help Cold War Americans imagine themselves as part of a racially and culturally diverse global society.

Officials of the United States Information Agency or USIA – the post-war governmental agency charged with overseas propaganda work – quickly began exporting both The Family of Man and the surround form more generally to countries on every continent. The USIA estimates that more than 7.5 million visitors saw The Family of Man abroad in the ten years after it opened in New York (Szarkowski 1994: 13). By the end of the 1950s, multiscreen arrays and multi-sound-source environments had become mandatory features of American exhibitions abroad, most famously at the Brussels World’s Fair of 1958 and the American National Exhibition in Moscow of 1959, where Khrushchev and Nixon staged their ‘Kitchen Debate’. In Brussels and Moscow, the original, industrial-therapeutic aims of Bauhaus artists and the pro-democratic ambitions of the Committee for National Morale came together once again on behalf of a new mission: taking personalities that might be drawn toward communism and turning their perceptions and desires in more democratic directions.

The states of mind that the USIA sought to create, however, were not quite the same as the ones that defined the democratic personality at the start of the Second World War, nor was the USIA’s surround quite the same form. Both had been changed by the embrace of a mode of control that had been part of the surround from its inception and by the rise of post-war American consumerism. In the 1940s, social scientists agreed that the democratic person was a free-standing individual who could act independently among other individuals. Democratic polity in turn depended on the ability of such people to reason, to choose and, above all, to recognize others as being human beings like themselves. For these reasons, wartime propaganda environments such as Steichen and Bayer’s Road to Victory turned away from the one-to-many aesthetics of mass media and constructed situations in which viewers could move among images and sounds at their own, individual pace. In theory, they would integrate the variety of what they saw and heard into their own, individuated experiences. This integration in turn would rehearse the political process of knitting oneself into a diverse and highly individuated society. Ideally, visitors would come to see themselves not simply as part of a national mass, but as individual human beings among others, united as Americans across their many differences.

The turn to the surround form in the Second World War thus represented a break away from the perceived constraints of mass media and fascist mass society. But it also opened the door to a new mode of social control. Visitors to Road to Victory may have been free to encounter a wide array of images, but the variety of those images was not limitless. Bayer and Steichen had designed the exhibition space and selected the pictures viewers would see. Likewise, at The Family of Man, visitors were free to move but only within an environment that had been carefully shaped by Steichen and his collaborators. When they compared it to the one-to-many dynamics of mass media and of fascism, many analysts at the time found the surround to be enormously liberating. Even so, from the distance of our own time, the surround clearly represented the rise of a managerial mode of control – one in which people might be free to choose their experiences, but only from a menu written by experts.

In the late 1950s, that managerial mode met an American state campaign to promote American-style consumerism abroad. Visitors to the American pavilion at the 1958 Brussels World’s Fair and to the 1959 American National Exhibition in Moscow enjoyed the same mobility and choice offered to visitors to Road to Victory almost twenty years earlier. But they also found themselves surrounded by a cornucopia of consumer goods. In the surrounds deployed in Brussels and Moscow, political choices and consumer choices became a single integrated system. The democratic personality of the 1940s in turn melted almost imperceptibly into the consumerism of the 1950s. The Second World War effort to challenge totalitarian mass psychology gave rise to a new kind of mass psychology, a mass individualism, grounded in the democratic rhetoric of choice and individuality, but practiced in a polity that was already a marketplace as well.

Surprisingly perhaps, it also helped give rise to the American counterculture. In the same years that the USIA was presenting The Family of Man around the world, John Cage was bringing his Bauhaus-inflected mode of performance to international music festivals, to the Brussels World’s Fair and to the downtown New York art scene. And like the USIA, Cage was working to create surrounds in which audiences could experience semiotic democracy. In The Family of Man, Edward Steichen hoped to surround museum visitors with images and so free them to see a whole world of people who were simultaneously unlike and yet like themselves. At about the same time, Cage was promoting modes of performance in which each sound was as good as any other, in which every action could be meaningful or not, a space in short, in which audience members found themselves compelled to integrate a diversity of experiences into their own individual psyches.

In the summer of 1952, Cage staged a performance at Black Mountain College that transformed his efforts to democratize sound into key elements of one of the defining performance modes of the 1960s, the Happening. No single, authoritative account of the event ex...