![]()

1 Waiting for Joseph Welch

“We were used by [him], but that’s the nature of reporting and television especially. It was a terrible dilemma. I’m sure every responsible news office in the country was worrying, ‘How the hell do you handle this kind of stuff when you know the son of a bitch is lying?’

You have to say what the guy is saying, but we couldn’t catch up with his lies fast enough before another one came out, so we were giving him this buildup. The more you wrote about him, even attacked him, the more powerful he became. This is what demagoguery is all about. The hope is eventually you catch up with the truth, but meanwhile the devastation that takes place lasts a long time.”

Joseph Wershba, See It Now reporter, on Joseph McCarthy

As I revisit my experience of television, I’m struck by the fact that my earliest memories and what is playing on my living room TV at this very moment are cultural bookends, beginning with the moment when TV helped bring down an authoritarian bully and ending with an authoritarian bully created and elevated by TV.

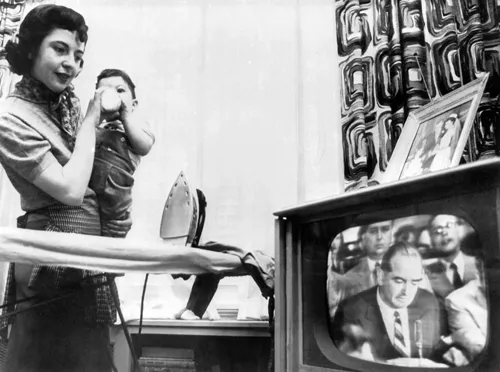

Figure 1 Watching the Army–McCarthy Hearings in April 1954 while doing women’s work. Everett Collection Historical/Alamy.

When you grow up with television, however, memory can be tricky. Did you see Oswald shot by Jack Ruby as it happened, live on TV? Or has your own experience become enmeshed with the mythologizing of that moment? I know I saw Oswald shot because my father and I were watching television together at the time. “Daughter”—he called me that when he was about to say something of great moment—“you just watched history made before your eyes.” Over the next few days, we saw that history made over and over, which was a novelty in itself. Replays—groaningly frequent—are now standard stuff in a 24-hour news cycle. How could they fill up the time without them? The anchors have difficulty managing the few minutes of banter they are required to perform with each other now; in the fifties, however, the evening news was only on once a day, and it took a truly extraordinary event to interrupt regular programming with replays.

So I know I saw Oswald being shot. But I’m not so sure about the McCarthy hearings. I would have been six-and-a-half years old, so I undoubtedly didn’t understand any of it; I would have been engrossed in something else—coloring, maybe, trying hard to stay inside the lines and create the masterpiece that I always expected of myself, searching for the burnt sienna crayon. Still, in some dim way I must have heard the famous words:

Until this moment, Senator, I think I never really gauged your cruelty or your recklessness . . . Senator, may we not drop this? We know he belonged to the Lawyer’s Guild . . . Let us not assassinate this lad further, Senator; you’ve done enough. Have you no sense of decency, sir, at long last? Have you left no sense of decency?1

When I scrutinize this memory, though, I find lots of reasons why it was implausible that I heard it as it happened. It was a Wednesday—June 9, 1954 to be exact—so my father would have been at “the place” (factory) in Brooklyn or downtown Newark, or more likely on the road, meeting with brokers in upstate New York. He loved politics, but my mother would have been watching Search for Tomorrow or The Guiding Light. And that day—the day that Joseph Welch socked it to McCarthy and turned the tide of the hearings—was June 9; wouldn’t I have been at school? After decades of watching political documentaries and teaching iconic televisual moments to my students, I can’t really be sure if I heard Joseph Welch demolish McCarthy as it happened. What I am sure of is that that moment is a standout in any narrative I would construct of my life as a television viewer.

Today, I long for another moment like that, which with one blow would send the edifice of authoritarianism crashing down—or expose a President’s corruption, as we had witnessed during the televised final six days of the House Judiciary Committee’s deliberations over Nixon’s impeachment. When the Committee brought three articles of impeachment against Nixon and the House voted to have the entire impeachment trial televised, Nixon resigned in a prime-time television address. He saw the cards for indictment were on the table. But also, after his fatal, sweaty showing during the Kennedy debates, he had learned to respect the power of television and the damage a televised trial could do to any standing he might retain in the history books.

At one point, we thought Robert Mueller might provide our Joseph Welch moment: The Report that would expose Trump once and for all. We waited and waited, and one of the digital savvy among us put together a startlingly realistic video spin on “The Untouchables,” in which Mueller, like some modern-day Elliot Ness, collared all the crooks from Flynn to Trump. Our pulses quickened and our hearts gladdened when we heard The Report was about to be released. But Mueller, bless him, thought history was still written with a quill pen. He actually expected Americans to read 400 pages of dense prose and do the right thing by it. He didn’t “get” television at all. But disastrously, Donald Trump and his Attorney General Bill Barr, following the Roger Ailes playbook, did. Trump and Barr understood that the phrase “No collusion,” said often enough before a viewing audience, could easily defeat evidence and argument.2

Watching Bill Barr replace Mueller’s painstakingly prepared, factually impeccable report with televised lies was especially deflating for those of us left-wing boomers whose politics had been grounded in the written word: Marx, The Port Huron Manifesto, Herbert Marcuse. Yet we are also children of television, so we harbored the fantasy of a politically explosive report delivered by a hero who, in a devastating moment of televised honesty and courage, would save us from our increasingly surreal “normalcy.” TV, as we were growing up, was full of transforming moments like that, both fictional and real. We weren’t ready for the possibility that the same televisual world that helped end a war via images of burning monks and fallen student protesters would also give us . . . Donald Trump.

![]()

2 We Have Six Televisions

Are you surprised? Do you imagine that because I am a critic of popular culture I wouldn’t be caught dead watching Dance Moms? If so, you’ve been reading too many academics who came to popular culture only after it became Europeanized and hot. When I was in graduate school, the voracious maw of theory had only begun to invade and chew up the objects of everyday life into unrecognizable form. There were as yet no popular culture departments, the closest you could get was film studies—within which you could study Nosferatu but not Jaws.

I was in philosophy because I loved history, was fascinated by the play of ideas in historical time, and enjoyed taking texts apart, foraging for their meanings. I was good with words, and I was a good arguer. It seemed a better place for me than any of the other disciplines. But my heart was elsewhere—it just hadn’t yet found a home in academia—and because I hadn’t the financial resources to strike out as a writer and these were the days when becoming a college teacher was still a fairly reliable path to earning a steady income, that’s what I did.

I also loved teaching. But I was frustrated by the bridge that I had to cross to make community with my students. Then one day I hit on the idea of asking them to write about how they experienced the duality of mind and body in their own lives—and discovered that Descartes was living right there, in their hatred of jiggling flesh and exaltation of their own will power to say “I can defeat you” to the cravings of their bodies.

Before long they were bringing in Nike “Just Do It” ads, talking about how Jennifer Aniston had been chubby as a child, and the bridge between the seventeenth century and the twentieth was crossed. And so, too, had the bridge between the future of my scholarship and my own experience: those things that I felt I truly knew about, having lived every day of my life with them—movies! television! magazines! commercials! The way they reflect and transform cultural change, and the way humans see themselves.

In short: I was not an academic who started out in the archives and gravitated toward popular culture when it became an accepted field of study. I was a popular culture fiend who went into academia because there was nowhere else for me to go—and discovered that the time was right for a marriage between my deepest interests and the latest thing in scholarship.

So, I don’t have six televisions because they are required for my work (although that’s what the IRS thinks). I have six televisions because I love television. I also hate television. But I’ve never found those two to be incompatible.

Here’s where my televisions live:

One is in the porch turned family room, where my treadmill lives. The treadmill was moved from the basement when my husband had cancer; a runner and bicyclist, he wanted to keep exercising while he recovered, but the mildewy basement wasn’t the place for a compromised immune system. So our lovely enclosed sunroom, surrounded by beautiful bushes and full of light, became a television room, where I now accumulate my daily steps quota with Netflix, Hulu or Amazon Prime.

We have a TV in the guest bedroom. And there’s one in my office, which is on just about all the time. Yes, I write with the television on. I learned how to do this growing up. Born in 1947, I can’t remember a time when television wasn’t a constant part of my life. Always eager to assimilate his immigrant roots to American life, my father was the first in our neighborhood to buy a TV, and it was always on.

There’s a huge television in the basement, a holdover from the days when my daughter played video games. No one has watched it since the room became trashed by Cassie and her live-in friend with half-drunk Ale-8s and old Reese’s wrappers.

The smallest television is in the bedroom my husband and I share. It’s the smallest because we only share the room marginally, given our vastly different sleeping and waking habits (I’m usually awake at 5:30, and am nodding off while he stealthily switches the channel to a sports event). Beyond sports, my husband rarely cares about what’s on the screen. He was born before the war, to a family of lawyers and founders of Cornell University. He grew up without television. Thus, it’s only a peripheral habit for him; he “watches” with headphones on, reading French newspapers on his laptop, learning new phrases, or practicing piano on his silent keyboard. When I ask him what he wants to watch as I scan the Netflix offerings, he rarely has preferences. “A British crime drama” is the most specific he gets—or one of the Jason Bourne movies. He’d be happy to watch one of those every day.

The most important television in our home is in the living room. That’s where my husband and I sit in the evening, watching MSNBC, shouting obscenities at pundits and politicians. It’s also where I often drift to sleep under a huge quilt, my three dogs nestled against (read: shoving) various parts of my body, unable to move myself to go to bed despite the fact that I’ve been relegated by Piper, Dakota, and Sean to about one quarter of the available space of the couch. It’s shaped my body into a permanent pretzel, and I’ve tried to wean myself of this habit, but like Toni Morrison’s Beloved, I can’t be evicted from that magnetic spot, not even by myself. My husband turns down the volume as he goes upstairs but I often wake in the middle of the night to the second round of Rachel Maddow in the background. The strangest thing: I sometimes wake at exactly the place where I nodded off during the nine o’clock show. It’s as though my television is keeping track of me.

Why can’t I move from the couch to the bedroom? Partly it’s the quilt—put me under a cozy enough one and I’m two years old again. Partly it’s the doggies, whose warm breath reassures me that sweetness and innocent, creaturely love still survives. But also—I simply can’t drag myself away from the television. To do so is to create a vacuum of dread for me. I’ve skewered broadcast news more ruthlessly than any other critic; yet at 10 p.m. the anchors become familiar, intimate friends whom I can’t bear to abandon. Or perhaps more precisely, I can’t bear to have them abandon me. They lull me to sleep with their gruesome news of the day. If I suddenly wake screaming from a nightmare, I look up and there’s some guest pundit pontificating, reassuring me that everything is still in place. At eleven o’clock, the very habits I criticize in my daytime writing—the “normalization” of the Trump disaster, the repetitive questions, the fact that they can still smile and joke in this hell we have descended into—calms me.

It’s just one of the many contradictions that comprise my relationship with television.

![]()

3 Growing Up in the Fifties and Sixties with Television

Television’s Split Personality

From the beginning, TV has had a split personality. On the one hand, fifties television was full of fairy tales and fantasies meant solely to entertain and soothe—and encourage viewers to buy commodities to furnish idealized suburban lives. June Cleaver boosted both the industries in female glamour and Westinghouse appliances by cooking her pies (the best in the neighborhood of course—no Miss Minnie’s in that white enclave) in pearls and heels. No one got cancer, Lassie always came home, and Father always knew best. We didn’t know at the time that Robert Young (slightly later to become the first beloved TV doctor, Marcus Welby) actually struggled with alcoholism, that Ozzie was a do...