![]()

1

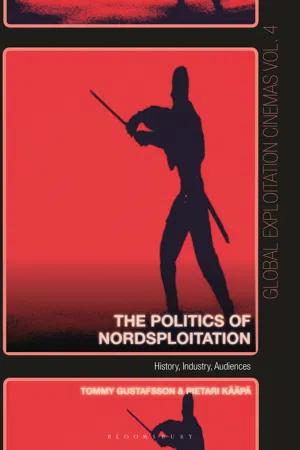

The politics of Nordsploitation

Nordic cinema holds a distinct international reputation as an austere, artistic, experimental and socially relevant body of enthusiastically serious film culture. This reputation can be traced back to the 1910s with highly acclaimed films like Afgrunden (The Abyss, 1910), Berg-Ejvind och hans hustru (The Outlaw and His Wife, 1918) and Körkarlen (The Phantom Chariot, 1920), which moved the boundaries for film art, and are still, 100 years later, called ‘poetic masterpieces’ (Tapper 2006: 41). For academic scholars, the tradition of Nordic art cinema, continued by filmmakers like Ingmar Bergman, ‘often functioned as a counterbalance to the hegemony of Hollywood’ (Soila, Söderbergh Widding, Iversen 1998: 1). As argued by the authors of the field-defining volume Nordic National Cinemas, Nordic film history has been understood as a national cinematic project, the rationale for which is built on three factors: (1) the films are not exportable to markets outside the region; (2) state influence coordinates the production of cinema as a national project based on closely guarded notions of artistic relevance; and (3) the films produced in these contexts exhibit a ‘national quality’ that is distinct from American film (Soila, Söderbergh Widding, Iversen 1998: 2–5). For us, this narrow nationalistic perspective is both misleading and unproductive, as it only tells one side of the (his)story. It imposes limitations on studying films that have found themselves on a collision course with these national perspectives, and invariably marginalizes them to the fringes of film history.

The Politics of Nordsploitation approaches Nordic cinema from a perspective that very literally turns these factors upside-down as we mainly study films that (1) are meant for export, (2) are produced without state support and outside of the national project of domestic film institutes and (3) have a transnational quality that mirrors American films in complex, and often unexpectedly subversive, ways. This approach is predicated not only on the choice of topic for this book, but by a realistic assessment of the histories of the five distinct Nordic film cultures. By only focusing on films that meet prescribed top-down designations of ‘quality’, the act of compiling national cinema histories has effectively written out a huge range of films that, in one way or another, have contributed to shaping these national film cultures, whether by instigating new co-production strategies or by catering to audiences overlooked by prescriptions of ‘relevant’ art cinema. Counteracting such mechanisms of exclusion, we explore Nordic film history to uncover the ongoing complex entanglements of cultural taste, commercial profit, social relevance and ethical norms that, for us, comprise the politics of Nordsploitation. Interactions among institutes, filmmakers, critics and audiences comprise negotiations on the parameters of cultural worthiness and artistic relevance that shapes the dynamics of inclusion and exclusion, of ‘belonging’, in these film cultures, and thus sets expectations for what can be considered exploitative.

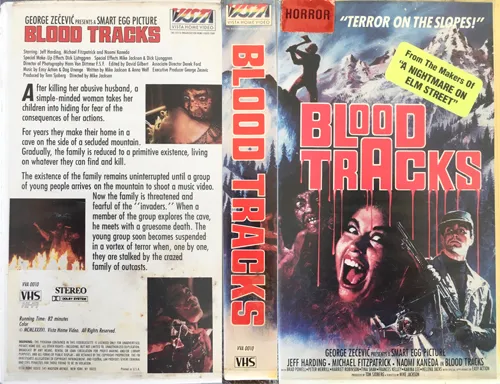

One striking example of the dynamics of inclusion and exclusion based on, first, perceptions of artistic taste and cultural value and, second, on unbalanced negotiations between the national and the transnational, is the Swedish slasher/stalker film Blood Tracks (1985). The ways these dynamics shape the writing of film history becomes explicit when we consider that this film is not mentioned even once in the annals of Swedish film history. Not only did it probably reach larger audiences than most other Nordic films during the 1980s, with distribution on VHS in multiple countries such as Sweden, UK, Japan, West Germany, Spain, Canada, Belgium, the United States, South Korea and the Netherlands, but it also benefited from distribution and promotional efforts in these markets that did not frame it as a Swedish curiosity.

For example, a sticker was attached to Blood Tracks’ ‘big box’ artwork distributed by Vista Home Video on the US market reading: ‘From the makers of “A NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET”’. The fact that the obscure Swedish filmmakers’ previous film, The Ninja Mission (1984), had been distributed in the United States by New Line Cinema with some success led to this unique association of a no budget Swedish slasher with Freddy Krueger, one of the icons of horror cinema. This rather far-fetched connection is typical of marketing in the video era but in our case, it underlines the peculiar circumstances in which Blood Tracks signifies much more than its to-date marginalized status in Sweden. Instead, it is a film that had sufficient commercial viability – a distinctly unusual quality at the time – to be marketed in tandem with the highly successful A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984) and which thus had the capacity to reach international audiences whom paid, watched and enjoyed the film – despite having been written out of ‘official’ domestic film history. Blood Tracks ticks all the boxes for the upside-down perspective on Nordic film history as it unquestionably was meant for export; it was produced without state support and thus excluded from the national project; and it unabashedly mimicked American genre film, in this case the slasher.

Figure 1.1 The original Blood Tracks ‘big box’ artwork for the US market with the sticker that reads: ‘From the makers of “A NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET”’, 1985. Courtesy of Vista Home Video.

Blood Tracks was directed by Swedish maverick film director Mats Helge Olsson under one of his Americanized aliases, in this case, Mike Jackson, a pseudonym suspiciously similar to megastar Michael Jackson. In many senses a run-of-the-mill slasher, the film is noteworthy for featuring plenty of examples of commercial audience diversification that helped it to stand out among contemporary American competitors such as The House on Sorority Row (1983) and The Mutilator (1984). First, Blood Tracks can be placed in the slim subgenre of Heavy Metal Horror as the equally slim narrative features Swedish glam rock band Easy Action travelling to the Colorado Mountains (in reality Swedish Funäsdalen near the Norwegian border) to shoot a music video. Second, it takes place during winter in the mountains, and thus includes snowy landscapes and a narrative that interacts with the cold weather as the band members and their groupies are killed off in one gruesome way after another. Snow-covered mountains were also featured on most of the international VHS covers, and in all the English-speaking markets, the imagery was coupled with the tagline: ‘Terror on the slopes!’

Although the Heavy Metal Horror genre included films like KISS Meets the Phantom of the Park (1978), Rocktober Blood (1984) and Trick or Treat (1986), the latter featuring Ozzy Osbourne and Gene Simmons, 1980s feature films, more than ever, used real-life rock and pop stars and music to promote both the films and the bands. In an interview with two of the members of Easy Action, Peo Thyrén and Bo Stagman, they readily admit that the main purpose for their participation in Blood Tracks was publicity. Then again, they contextualize this decision by stating that Prince ‘did the same thing’ with the film Purple Rain (1984), although they are clearly aware that Easy Action, and the film they took part in, did not remotely play in the same league (Blood Tracks: ‘Blodspår – Easy Action sopar igen spåren’, 2012).

The commercial and international calculations made by the members of Easy Action, their label Warner Music, and Mats Helge Olsson, are especially intriguing in their cultural–political implications. When Peo Thyrén first contacted Mats Helge Olsson, the latter was in prison where he was serving time for debts that he had obtained as producer of Sverige åt svenskarna (‘Sweden for the Swedes’, 1980). Olsson immediately realized the commercial possibilities of the project and included music by Easy Action in an already ongoing film project and ensured that filming on their collaborative production started a few weeks later (Blood Tracks: ‘Blodspår – Easy Action sopar igen spåren’, 2012). To ensure that the film would not be forced to try to claw back profit from the insubstantial Swedish audiences, Blood Tracks was produced by Smart Egg Pictures, a London-based company that, among other films, co-produced A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984) – thus certifying the ‘associated’ connection on the VHS sticker – but also several instalments of the extremely successful Swedish franchise Sällskapsresan (The Charter Trip).

International connections were emphasized from the inception as the language of the film was English and most of the actors, besides the five members of Easy Action, were British and consisted of female photo models with no prior experience and male actors, of whom Jeff Harding was the only one to carve out a career in the film industry with supporting roles in films like Spies Like Us (1985) and Alfie (2004). While the snowy surroundings for the killings in Blood Tracks could be seen as locally ‘exotic’ for the slasher genre, underneath this superficial internationalism, its Colorado locations are, for example, undermined by the fact that all car license plates are clearly Swedish. Unlike the contemporary wave of Nordic Noir film and television series that use ‘the more or less stereotypical distinctiveness of the Nordic countries in terms of national characteristics and temper, landscape and climate, and various cultural associations or markers’ (Åberg 2015: 95), Blood Tracks, decades before, could – and would – only draw attention to the one distinctively ‘international’ Swedish feature, snow, while concealing as many of the location’s other domestic characteristics as possible.

Clearly, no one involved in this project wanted to contain it to Sweden, where Blood Tracks was not even released theatrically and thus not rated by the Swedish Board of Film Censorship. The facts that this film received its main distribution internationally and was only released domestically on VHS are both contributing factors to its rejection from national film history. These circumstances are not necessarily that unique as in analysing marginalized underground or exploitation films in Europe, Ernest Mathijs and Xavier Mendik identify what they call the two corners of underground and exploitation film. The former includes artistic films that aspire to be alternative but are regardless ultimately included in national canons, whereas the latter comprise films ‘that do not belong to the recognized repertoire, mostly because they are not deemed worthy enough. This latter category of films wants to become popular, but is often prevented of becoming part of the cinema establishment because the films are continuously dismissed as cheap or irrelevant rubbish’ (Mathijs and Mendik 2004: 3–4).

It is not difficult to identify how Blood Tracks could be positioned in these arguments. Despite all of its international achievements, it was obviously considered as ‘irrelevant rubbish’ by Swedish authorities, but does this mean that films like these are not worthy of research or of inclusion into writing film history? Undeniably, the content of Blood Tracks, in this case a slasher with plentiful conventional nudity and gore for its genre, would have had an impact on both contemporary and historical assessments of the constitution of Swedish cinema, despite and thus perhaps because of, its often active marginalization from these confines. Trash does not imply only inherent low-budget characteristics, such as bad acting, poor editing and a weak screenplay, but also subjects and themes that typically include violence, disturbing images of distress and the seemingly senseless objectification of the female body. The act of labelling a film such as this as trash would have thus constituted a means of drawing boundaries between the acceptable and the impermissible in film culture, an act which in itself is heavily politicized, and which consequently reveals much about the dynamics of the so-called national project.

Mathijs and Mendik confront, and at the same time legitimize, this somewhat sensitive subject by discussing recurring issues in European underground and exploitation cinema. On the one hand, many films ‘address issues of guilt, confession and testimony’ in relation to ‘the massive traumas of World War Two, the rise and collapse of communism, and decolonisation’. On the other hand, there is also a persistent characteristic of ‘resistance, rebellion and liberation’, where European underground and exploitation cinema positions itself against a mainstream culture, but also against hegemonic ways of reasoning, politically and ideologically. ‘Arguably, alternative European cinema [. . .] does not always campaign for politically correct perspectives. But at the very least it seems to be championing, almost anarchically, a call for liberty’ (Mathijs and Mendik 2004: 4–5).

To readdress this unbalance of power in writing national film histories, The Politics of Nordsploitation is primarily interested in ‘forgotten’ films that are typically categorized as cheap and irrelevant by cultural authorities, and if they happen to attract attention internationally, their domestic roots are conveniently forgotten. However, unsurprisingly, the (his)story of these films is by and large defined by resistance and rebellion against the national project, against a mainstream film culture and against censorship. In the interview with the two members of Easy Action, Mats Helge Olsson’s film production practice was tellingly equated with the punk scene of the late 1970s, that is, as rebellious and defiant cultural production aimed against the norms of Nordic societies (Blood Tracks: Blodspår – Easy Action sopar igen spåren’, 2012). These anti-establishment views, primarily consisting of nonconformist and anti-authoritarian ideological perspectives, and a do-it-yourself ethos, are attitudes that permeate the primary source material of this study. The big difference being, of course, that exploitation cinema has never been anti-commercial but instead has tried its best to be as commercial as possible.

Hence, the rationale of The Politics of Nordsploitation is to rewrite Nordic film history by focusing on exploitative tendencies and alternative ways of produc...