![]()

1

INTRODUCTION: TOWARD A CROSS-FERTILIZATION BETWEEN KURDISH AND YEZIDI STUDIES

Güneş Murat Tezcür

Introduction

The experience of victimhood has been a core aspect of both Kurdish and Yezidi political self-identifications and narratives in modern times. Kurds are a paradigmatic persecuted ethnic minority; Yezidis are a paradigmatic persecuted religious minority. Kurdish victimhood primarily derives from the experience of being a suppressed ethnic minority by four Middle Eastern states, for example, Saddam’s genocidal Anfal campaign involving massive usage of chemical weapons. Yezidi victimhood, which has a longer lineage, primarily derives from the experience of persecution at the hand of Muslim rulers and neighbors based on a code of religious difference, for example, the genocidal campaign involving sexual slavery by the self-styled Islamic State (IS). The Kurdish politics of memory is an unbroken history of state violence, lack of political unity, and frustrated national ambitions. The Yezidi politics of memory is an unbroken history of violent firmans (i.e., military campaigns) by Ottoman pashas, Kurdish amirs, and Muslim clerics. Consequently, the Kurdish and Yezidi remembrance is primarily the memory of wounds. To paraphrase Milan Kundera’s famous quote, the Kurdish and Yezidi struggle against hegemonic states and religious entities is the struggle of memory against forgetting.

It is tempting to take these distinctive but overlapping visceral experiences and memories of victimhood as the basis of a comparative study of Kurds and Yezidis. Such a study could start with the premise of how ethnic and religious persecution and violence have shaped the basic contours of these two communities’ daily experiences and political struggles. While such a premise would be promising, it could also be misleading without a systematic attention to the agency of Kurdish and Yezidi actors in effectively challenging hegemonic projects through various forms of physical and symbolic resistance. It would also ignore how the politics of memory inevitably tends to be highly selective and entails the politics of forgetting.1 The sharp distinction between victim and aggressor is not sustainable in certain historical contexts characterized by shifting alliances, porous identities, and contentious politics.2

This book transcends victimization narratives and offers a comparative study of Kurdish and Yezidi experiences with each other and other groups in the Middle East in both historical and contemporary times. It aims to offer fresh and nuanced perspectives about multidimensional identities and shifting borders characterizing these dynamic experiences. In doing so, it focuses on historical processes shaping the evolution of political identities and discusses the centrality of intersubjective perceptions, which are informed by power asymmetries, to these processes. It includes contributions from both established and emerging scholars that speak to multiple disciplines including political science, sociology, history, and cultural and area studies. The contributors, coming from different geographical and institutional settings, engage with similar themes from distinctive scholarly traditions.3 All chapters are based on original empirical research, including fieldwork (primarily in Iraqi Kurdistan), archival study, or survey data.

The book has three distinguishing characteristics. First, it is the first systematic study covering Kurdish and Yezidi experiences in a comparative and integrated way. Yezidis are a primarily Kurdish-speaking group with a distinctive religious belief system. A group historically lacking an established intellectual class and written record, they have attracted the interest of travelers, soldiers, scholars, and statesmen since the early nineteenth century. At the same time, there has been limited engagement with the large field of Kurdish studies.4 Yezidis remained on the margins of scholarly works about Kurds before the tragedy in August 2014 generated significant public and academic interest in the Yezidis.

The long-lasting marginality of Kurdish studies in the Western academia further aggravated the isolation of Yezidi studies. Most of the extant work focused on Kurdish interactions with more hegemonic actors, the Iranian, Iraqi, Syrian, and Turkish states that hindered Kurdish aspirations for greater rights and power with repression and violence since the early twentieth century. As a result, the intra-Kurdish relations and minorities in Kurdistan, such as Armenians and Yezidis, received much less systematic attention—until very recently. This book aims to facilitate a greater degree of communication and integration between Kurdish and Yezidi studies. As I elaborate further below, the book engages with two overarching and interrelated themes to facilitate greater dialogue between Kurdish and Yezidi studies: (a) formations of Kurdish and Yezidi political identities in different historical settings and (b) intersubjective perceptions of Kurds and Yezidis by their neighbors and hegemonic powers. As several chapters in this book demonstrate, studying how both more powerful societal groups such as ethnic Turks in contemporary Turkey and less powerful groups such as the Armenians in the early twentieth-century eastern Anatolia and the Yezidis in the early twenty-first century perceived Kurds opens up new avenues of promising research and valuable insights about peace and conflict characterizing intergroup relations.

Second, the book presents novel interpretations based on original empirical research with a truly interdisciplinary approach. Chapters employ both quantitative and qualitative methods to address similar questions about identity formation and intersubjective perceptions. Several chapters utilize in-depth interviews with a wide range of ordinary people ranging from Kurdish refugees who fled from Turkish counterinsurgency operations to the relative safety of Iraqi Kurdistan in the 1990s to Yezidi survivors of the 2014 genocidal attacks. Other chapters utilize historical material, including a canonical Kurdish text from the late seventeenth century, writings of Western travelers to Kurdistan from the nineteenth century, and local Armenian newspapers from the early twentieth, and Arabic sources from the mid-twentieth-century Iraq. Another chapter utilizes a nationally representative survey conducted in Turkey. This methodological diversity and richness of empirical sources in primary languages, including Kurdish, Armenian, Arabic, and Turkish, reflect the increasing maturity of scholarship on Kurdish and Yezidi issues.

Finally, the book develops innovative conceptual approaches exploring shifts in the majority-minority relations characterized by both dominance-subordination and coexistence-cooperation. It engages with broader scholarly literature such as minority rights and democratization, politics of identity, nationalism, political violence, and refugees. In particular, various chapters suggest how the notion of victimhood is a historically contingent process. An ethnic or religious group may be the victims of stronger neighbors or colonial powers while appearing as a repressive force in the eyes of an even weaker minority. This dualistic dynamic is particularly insightful in exploring the contemporary evolution of Kurdish-Yezidi relations in Iraq characterized by patterns of solidarity in the face of common enemies but also mutual suspicions and tensions.

I now offer a brief overview of the evolution of Kurdish and Yezidi studies in the last several decades. Building on this overview, I then present a thematic road map that summarizes the main arguments of the chapters organized along two sections.

Renaissance in Kurdish Studies and Revival of Yezidi Studies

One of the negative implications of Kurds lacking a state of their own is the fragmentation and marginalization of Kurdish studies.5 Among other reasons, the division of the Kurdish homeland among four states controlled by three dominant linguistic groups (Arabic, Persian, and Turkish), the suspicion and hostility of these states to any work deviating from their ruling ideologies, and the lack of resources available to and continuing restrictions on Kurdish language hampered scholarly studies on Kurdish people for a long time.6 In comparison, Yezidi studies remained an even more insulated and smaller field of inquiry despite a number of notable contributions on the origins, evolution, and nature of Yezidism since the early 1990s.7 As Christine Allison noted, Yezidis, practicing a set of religious beliefs transmitted primarily orally, were a subaltern group even among Kurds.8 The historical marginality of Yezidis has inevitably limited scholarly and public interest about the group.

The geopolitical developments and popular struggles in Kurdish lands in the last two decades have led to some sea changes, including unprecedented forms of Kurdish nationalist mobilization and governance. While Kurdish aspirations for secession from Iraq resulted in a bitter failure in the fall of 2017, the widespread image of the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) as an island of stability in a country of chaos has remained well-anchored.9 Meanwhile, the diversification and popularization of Kurdish nationalist movement in Turkey, despite major setbacks in the post-2015 period, have introduced an unprecedented element of democratic struggle to Kurdish activism. More recently, the formation of Kurdish self-rule in northern Syria and the rise of the Kurdish armed groups as the most important local ally of the Western coalition in the fight against the IS enhanced the global visibility and prominence of Kurdish politics. Besides, the technological revolutions, including rapid growth in social media, greatly expanded the interconnectedness and awareness of a Kurdish public sphere. All these macro-level dynamics have had positive implications for the academic study of Kurdish issues that attract a large number of talented, ambitious, and well-trained young scholars in many disciplines.

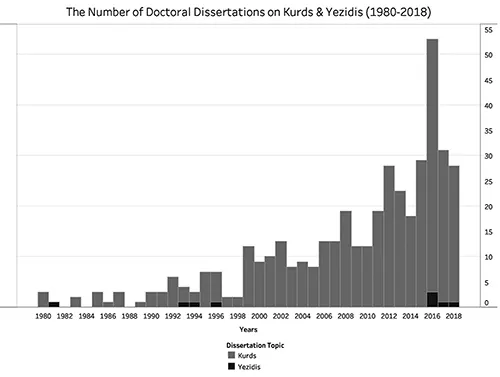

Figure 1.1 shows the number of English-language doctoral dissertations that focus on Kurds and Yezidis (i.e., mentioning the terms Kurds, Kurdish, Kurdistan, Kurd, or Yezidi, Yazidi, or Ezidi) from 1980 to 2018. An overwhelming majority of these dissertations were completed either in British or American universities. While there are 418 dissertations on Kurds, there are only nine dissertations on Yezidis.10 There has been a steady increase in scholarly interest in Kurdish issue especially after 2005. It is not coincidental that this current period has seen the consolidation of Kurdish self-rule in Iraq, the rise of Kurdish sociopolitical activism in Turkey, the growing influence of the Kurdish diaspora in Europe, and, most recently, the formation of de facto Kurdish autonomy in Syria. This rise has a convex shape suggesting that the last few years saw a more rapid increase. For instance, there were more than fifty dissertations studying various aspects of Kurdish issues in 2016 alone. Overall, the proliferation of publications, including articles in leading social science journals and books published by top university presses, indicates the growing vibrancy of Kurdish studies as an academic field that attracts greater scholarly and public attention than ever.11

Figure 1.1 The Number of Doctoral Dissertations on Kurds and Yezidis

Source: Proquest Dissertations & Theses (compiled in October 2019). The graph shows only English-language dissertations.

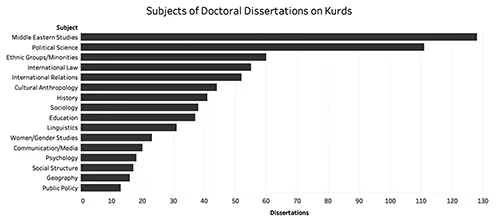

Figure 1.2 shows the disciplinary subjects of doctoral dissertations on Kurds. Not surprisingly, a plurality of dissertations are classified under the subject of “Middle Eastern Studies.” Interestingly, there are also a large number of dissertations in political science, international relations, and international law. This pattern suggests that scholarly interest in Kurdish issues parallels the growing importance and visibility of Kurdish political actors in domestic, regional, and international arenas, as mentioned above. At the same time, the fact that many other disciplines, such as cultural anthropology, history, and sociology, are well represented in the dissertations shows the growing breadth and scope of Kurdish studies.

Figure 1.2 Subjects of Doctoral Dissertations on Kurds

Source: Proquest Dissertations & Theses (compiled in October 2019). The graph shows only English-language dissertations.

In comparison, scholarly interest in Yezidis continues to remain very limited. It is clear that the tragic events in August 2014 have triggered scholarly interest in the group. Five dissertations were completed on the community from 2016 to 2018.12 Yet there were only four English-language doctoral dissertations dealing with any aspects of Yezidi people from 1980 to 2000.13 Even more strikingly, there was not a single dissertation on the community for twenty years, from 1996 to 2016.14 Major books on Iraqi and Kurdish politics published during this period barely mention Yezidis at all.15 This lack of scholarly attention partially reflects the fact that Yezidis were a relatively small demographic group that lacked strong international connections and remained on the margins of politics in modern Iraq. Yet Yezidis’ perceived heterodoxy and the lack of a written tradition are also likely to play a role in their invisibility in such works. Even the conventional description of Yezidism as a “syncretistic” religion implies its lack of originality and reflects its marginality.16 After all, all religions evolve in close interaction with and often incorporate beliefs and practices from each other. Only with the rise of orthodox interpretations often backed by political power, a homogenous and puritan stance imposes itself.

Overall, the upward trend in both Kurdish and, to a limited extent, Yezidi studies is likely to accelerate in the upcoming years given the continuing saliency of Middle Eastern geopolitics and the rise of a new generation of scholars. Research on Kurdish and Yezidi society and politics will also strongly benefit from comparative studies informed by broader scholarly perspectives and discussions. With this premise, a central contention of this book is that cross-fertilization between the studies of Kurdish and Yezidi people would be mutually beneficial and lead to unique conceptual insights and original empirical findings.

A Thematic Overview: Formations of and Perceptions of Group Identities

This book brings together nine chapters providing conceptually insightful and empirically rich studies about the formation and perceptions of Kurdish and Yezidi political identities. The first thematic section includes four chapters and concerns the formations of Kurdish and Yezidi political identities in various historical settings. The second theme is about intergroup relations and revolves around five chapters discussing perceptions of Kurds and Yezidis by their neighbors and external actors (i.e., Ottoman-Yezidi, Armenian-Kurdish, Western-Kurdish, Turkish-Kurdish, and Kurdish-Yezidi). In each case, the asymmetric nature of these perceptions reflects power dynamics underlying intergroup relations. While extant scholarship has dealt with the state-Kurdish relations extensively, the topic of intergroup relations in Kurdish lands has attracted less attention. Chapters in this book aim to address this gap and operate under the analytical assumption that the emergence and evolution of group identities are historically contingent (not deterministic) processes that are conditioned by interactions among groups, states, and external powers. This approach is an antidote against “groupism,”17 the tendency to treat social entities as being monolithic, homogenous, and externally closed, as it focuses on the process of identifications through which such entities come into existence and gain widespread acceptance, typically as a result of political struggles.

In particular, the boundaries between Kurdish and Yezidi identities have never been fixed and have been a primary source of historical contestation. On the one hand, the rise of secular Kurdish nationalism in the second half of the twentieth century allowed Kurdish leaders to aim to transcend religious differences and represent Yezidis under a nationalist framework, hence the hyphenated identity of Yezidi-Kurds.18 The promise of secular Kurdish nationalism has been the reconfiguration and recognition of Yezidism as the original religion of Kurds.19 In fact, secular Kurdish...