![]()

1

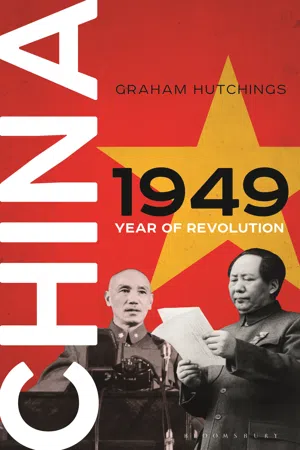

Adversaries

‘The enemy will not perish of himself’

The tone, content – indeed, the very title – of Mao Zedong’s New Year address to the Chinese people issued on 30 December 1948 could hardly have been more different from the solemn yet mild message to be delivered on New Year’s Day by the beleaguered Chiang Kai-shek. It was entitled ‘Carry the Revolution Through to the End’, and whereas Chiang proffered peace talks with his foes, even offering to stand down to facilitate them, Mao pledged to overthrow the Nationalist leadership, eliminate the influence of their imperialist backers and upend the entire social order of which they both were part.1

‘The Chinese people will win final victory in the great War of Liberation. Even our enemy no longer doubts the outcome’, he declared.

The annihilation of the Guomindang’s main forces north of the Yangtze River greatly facilitates the forthcoming crossing of the Yangtze by the People’s Liberation Army and its southward drive to liberate all China … Public opinion the world over, including the entire imperialist press, no longer disputes the certainty of the country-wide victory of the Chinese People’s War of Liberation.

Mao castigated the Nationalist leaders as ‘gangs of bandits’ and ‘venomous snakes’, demanding that Chinese people show them no mercy. The revolution must not be abandoned half-way for ‘the enemy will not perish of himself’.2

If Chiang Kai-shek felt that his world was collapsing round him after a year of calamities, Mao, while perhaps not brimming with quite as much confidence as his uncompromising address suggested, felt that he and the communist movement of which he had been the undisputed leader since 1945 was on the brink of what until recently had seemed unimaginable: the conquest of China. Chiang had been chasing Mao around the countryside for years; it now seemed that Mao might be able to drive Chiang out of China altogether. Mao was destined to enter the ranks of the world’s greatest leaders; Chiang was about to drop out of them.

Six years and some 450 miles separated the birthdays and birth places of the two men battling for control of their country. Chiang, the elder of the two, came into the world on 31 October 1887 on the second floor of a salt store in Fenghua, Zhejiang province, a traditionally prosperous part of China, south of Shanghai. His father was a salt merchant with whom he was to have a difficult relationship. He had nothing but tender feelings towards his mother.

Mao was born on 26 December 1893 in Shaoshan, a village surrounded by fertile rice paddy in Hunan province, south central China. His father was a rich peasant, a class of person whom his son’s revolution would later cast into jeopardy. The young Mao hated his father but, like Chiang, adored his mother.

As they matured, the two men continued to have much in common yet remained a study in contrasts. Intelligent, resourceful, determined, they both immersed themselves in the struggle to change China for the better that dominated much of the political life of their country in the early decades of the twentieth century. Both were shamed by their country’s weaknesses; both were determined to do something about it, often at great personal risk. They fought on the same side for a while, rallying to the cause of National Revolution in the early 1920s championed by Sun Yat-sen, leader of the ‘reorganized’ GMD, and backed by the Soviet Union.

Yet doctrinally and in terms of their visions for the future of their country the two men were miles apart. And while they both possessed extraordinary will power, confidence and sense of mission, it was to very different ends. Ultimately, it was communism that divided them.

Chiang, who had seen something of it first-hand during a study trip to Moscow in 1923–4, was unimpressed, though he admired the discipline of the Red Army, enforced by its political commissars. ‘Proletarian revolution was not appropriate for China’, he told his startled hosts.3 Mao was a firm believer in the Marxism to which he had been introduced at an early age and which, so he and his supporters claimed, he had since adapted to Chinese conditions with such extraordinary success. He had never been abroad but was at this precise moment badgering Joseph Stalin for an invitation to visit Moscow in the hope that he could secure an alliance between their two countries.

Chiang was supremely confident in himself and his civilization, thanks to a sense of personal destiny reinforced by his conversion to Christianity. His diary reveals him to have been a devout man, a regular reader of the Bible, reflective and self-critical. Disciplined and restrained in public (except under pressure of the kind that caused him to storm out of the New Year’s reception), he was in many ways a traditional figure, Confucian in outlook and convinced that many of the answers to China’s problems lay in improving the moral behaviour of its people. ‘We must … endeavour to improve our social customs and habits … reform our intellectual life and foster a spirit of freedom and government by law’, he wrote in the conclusion of his China’s Destiny, published in 1943.4

Mao was made of different stuff. He was a man of more grandiose visions eager to place developments in China in a wider international framework. This was striking given that his knowledge of the outside world seems to have been acquired mainly through Soviet or Marxist sources. Cruder, crueller and even more ruthless than Chiang, Mao’s manners and modes of speaking bore the hallmarks of his Hunan peasant origins. The same was true of his dialect, which seems to have been as hard for many of his fellow countrymen to understand as Chiang Kai-shek’s thick Ningbo accent.

Yet what ultimately differentiated the two men at the close of 1948 was the simple but critical matter of success – politically and on the battlefield. Mao had led the Communist Party and its armies to the brink of victory. This was striking testimony to his ability to motivate, lead, catalyse and organize a widespread desire for change in a huge, diverse country and in the most difficult of conditions. It was also an indictment of Chiang Kai-shek’s failings in this regard.

Heavy-set, stocky, by now thrice married and the father of at least six children, Mao had just turned fifty-five at the close of 1948.5 He was in indifferent health thanks to what would later be diagnosed as a low-grade malarial infection, bronchitis and what probably was both cause and effect of his condition: insomnia.6 Usually clad in matching baggy jacket and trousers, his hair long and floppy rather than the coiffured look of later years, he had since late May been living in Xibaipo, a small village on the eastern edge of the inaccessible Taihang Mountain range in Hebei province, some 200 miles southwest of Beiping. The Taihang marks the eastern boundary of China’s loess plateau, separating Shanxi province to the west from Hebei in the east and pushing south into Henan province. Xibaipo was a hamlet of 100 households or so, on the north bank of the Hu river. The yellow baked-mud walls of its simple dwellings were surrounded by mountains and set among cypress trees. The nearest city, Shijiazhuang, was 60 miles away to the southeast. The PLA had taken it from the government the previous December, the first urban centre in north China to fall into communist hands.

Mao had settled in this small, picturesque location after more than a year wandering through remote parts of northern Shaanxi with his personal bodyguards and small detachments of troops. He spent much of this time avoiding (often without much apparent difficulty) government forces under General Hu Zongnan, which in March 1947 had forced the Party out of its wartime base of Yanan. Chiang made much of his capture of the CCP’s headquarters; at the time, he seemed to have the upper hand in the struggle against his rival. But it was an illusion. His troops, desperately needed elsewhere, soon evacuated Yanan, which the communists reoccupied in April 1948.

MAP 1.1 Xibaipo, location of Mao Zedong’s headquarters in early 1949.

At home in the courtyard house in Xibaipo that he shared with his wife, Jiang Qing, Mao concentrated on the conduct of military operations and plans for China’s political future. Key Party leaders moved into houses nearby. They included Zhou Enlai, fifty, perhaps best described as Mao’s ‘fixer’ both within the Party but especially in terms of relations with those outside of it, including foreigners; Liu Shaoqi, second-ranking figure after Mao, just a few months younger than Zhou, a labour leader, specialist in Party organization, and most recently architect of a tempestuous but transformative land-reform movement; and Zhu De, some dozen years older, who was commander in chief of the PLA. Secure in their rural enclave, and far removed, in every respect, from the modern offices and grand government buildings of Nanjing, from which Chiang and his coterie watched their regime crumble, these disciplined, committed, battle-hardened men put the finishing touches to their plans to conquer and transform China.

Following a Politburo meeting held in the village in September 1948, Mao delivered a progress report. The communists were by now in control of about one-quarter of China and one-third of its population. In areas of North China with a population of 44 million a ‘unified people’s government’ had been set up in which the Communist Party was cooperating with ‘non-Party democrats’.7 Two months later, he declared that communist troops (whose number he put at three million) had achieved numerical superiority over government forces (which, after the ‘loss’ of Manchuria, he said totalled 2.9 million). The war would therefore end quicker than had been expected. ‘The original estimate was that the reactionary Guomindang government could be completely overthrown in about five years, beginning from July 1946. As we now see it, only another year or so may be needed to overthrow it completely.’8

Accordingly, his New Year address was full of plans for the future. In 1949, a Political Consultative Conference would be convened, ‘with no reactionaries participating and having as its aim the fulfilment of the tasks of the people’s revolution’. The People’s Republic of China would be proclaimed, and a central government established. It would be ‘a democratic coalition government under the leadership of the Communist Party of China, with the participation of appropriate persons representing the democratic parties and people’s organizations’. Mao set these measures in an almost cosmic context: ‘In our struggle, we shall overthrow once and for all the feudal oppression of thousands of years and the imperialist oppression of a hundred years. The year 194...