![]()

1

The Social Animal

Just as the appearance of Cotte’s translation of Locke in 1700 likely inspired intellectual debates over the acquisition of knowledge through the senses—a capacity the human shared with the nonhuman animal—artistic innovation around the turn of the eighteenth century was beginning to challenge the traditional hierarchy that always privileged human discourse over the more material concerns of social interaction and sensual appeal. Animal subjects proved particularly adept at capturing the vicarious response of viewers within this new artistic environment, especially when artists projected animal sociality as a central, engaging theme. I use the term “sociality” specifically for its encompassing application to nonhuman and human animals alike: unlike the term “sociability,” which conjures humanistic intercourse, “sociality” is used by ethologists to describe the deliberate behavior of animals interacting in groups, and also applies to any group of individuals associating in communities.1 New forms of interior design and portable arts emerging around the turn of the eighteenth century highlighted such shared sociality by mingling animals and humans in a single realm of ludic interaction. The Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture, newly receptive to innovations in the more sensual aspects of art—Rubensian color, buoyant compositions, amorous themes2—proved equally open to assessing the potential merits of the material, nonhuman realm.

A catalyzing force in this movement toward sociality as well as the shift in Academic expectations was the painter and designer Alexandre-François Desportes. Having received his initial training with Nicasius Bernaerts, a Flemish animal specialist who was himself the first in his chosen genre to receive admission into the Royal Academy, Desportes also worked as a court portraitist in Poland early in his independent career. He was thus ideally positioned to refashion the seventeenth-century genre of animal painting into sensually appealing and surprisingly social tableaux which would elicit interest and even a form of self-recognition on the part of cultured viewers. Like his colleague Antoine Watteau, Desportes mined the new decorative structures of the grotesque for a means of integrating his groups through a seemingly “natural” physical elegance that also connoted communal interaction; but while Watteau’s characters emanated from the theater and fashionable society, Desportes’s protagonists featured nonhuman animals familiar from the hunt, the boudoir, and, on occasion, the menagerie. Refined but almost never anthropomorphized, the creatures that populate these animalistic fêtes galantes model a new kind of engaged sensuality. Both Desportes himself and other designers would further develop the social animal subject as a vibrant agent in the form of portable arts ranging from fire screens to porcelain, yielding a veritable Rococo ecology of lively and interactive matter.

Desportes’s Self-Portrait as a Hunter

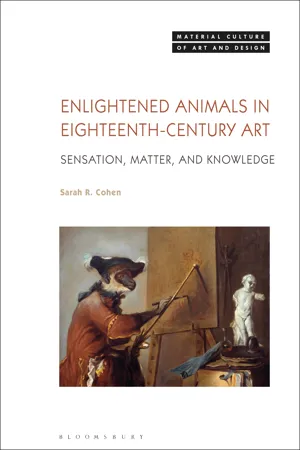

In 1699, Desportes publically allied his own artistic practice with the material life of animals when he displayed his Self-Portrait as a Hunter in the official exhibition of the French Royal Academy of Painting (Figure 1.1). He had presented the work as his morçeau de réception earlier in the same year, where it was described as “a huntsman surrounded by animals”; now, however, the generic “huntsman” transformed into the painter himself and the animals into his assistants and the very substance of his art.3 The work immediately impressed its audience, drawing praise for its vividly rendered creatures.4 Elegantly attired with an aristocratic hunter’s slight déshabillé, the artist sits beneath a tree at the edge of a spacious park, his gun in one hand and his dogs attentively flanking him. A trompe l’oeil pile of dead game spills downward and outward from the triangle formed between dogs and man; fur and feathers soft and glistening, the dead animals complement the hunter’s own spiraling posture and richly textured garments. The group unites through a network of interconnected legs, torsos, heads, feet, eyes, ears, and wings, topped by the hunter’s arms and hands and his sidelong, outward gaze. Although clearly in command of the animal life and death that surround him, the artist-hunter also demonstrates his material involvement with it, by closely allying his body with those of his dogs and his prey. If our eye at first follows the turned heads and gazes of the dogs to study the hunter’s face, it then travels down the arm that embraces the spaniel to encounter the long, human fingers, which are deftly matched by the dog’s outstretched foreleg and the brilliant white wing of an upturned duck. A shimmering fold of the hunter’s waistcoat abuts the canine foreleg just where the avian wing touches it from the other side, showing three ways in which a body can be clothed and ornamented. Using a still life artist’s rhymes and repetitions to assemble his carefully crafted forms, Desportes equally joins man to animal through the context of material display.

Figure 1.1 Alexandre-François Desportes, Self-Portrait as Hunter, oil, 1699; Paris, Louvre; photo: © RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource, NY.

In his studies of this painting,5 Pierre Jacky has noted that the artist’s subject in effect combines two genres familiar in France, as elsewhere in Northern Europe: the aristocratic hunt portrait and the dead game still life. Having been asked by the Academy, upon his aggrégation in 1698, to decide whether he wished to be received as a portraitist or as a painter of animals—Desportes having demonstrated skill in both capacities through the paintings he had presented—he chose the latter and promised to present as his reception piece “a subject of several animals.”6 Some surprise must thus have attended the Academicians’ reception of the Self-Portrait as Hunter, whose integrated theme allowed Desportes quite literally to “deliver” the promised animals, captured and presented by the hunter-artist himself.

As Jacky has argued, with his tour-de-force combination of portraiture and painting of animals both alive and dead, Desportes was probably attempting to elevate the genre of animal painting, which fell below portraiture in the Academy’s thematic ranking.7 Although the academicians followed their original plan to receive the artist as an animal painter, Desportes’s initiative succeeded from a marketing standpoint, by appealing to the aristocratic culture of the hunt. Immediately following the Self-Portrait as Hunter, the artist began to execute numerous other portraits of hunters with their dogs and prey, and the theme was quickly adopted by other artists—portraitists and animal painters alike—such as Jean-Baptiste Santerre and Jean-Baptiste Oudry.8 Having already secured royal patronage through his position as court portraitist in Poland in the mid-1690s, and, upon his return to France, in decorative work for the Dauphin at his château at Meudon, Desportes may have hoped that the Self-Portrait as Hunter would further his career in the French court. Indeed, the artist began to receive commissions of hunt paintings for French royal residences around the turn of the eighteenth century, when he undertook decorative projects for the Ménagerie at Versailles, as well as portraits of Louis XIV’s dogs for the château of Marly. Desportes would continue to execute paintings and decorative designs on hunting themes for the French court throughout the rest of his career.9

Thus advancing the official status of animal painting, Desportes also advanced the status of the animal itself as a viable pictorial protagonist. So allied is the artist with his living and recently felled subjects, the Self-Portrait as Hunter in effect becomes a new kind of group portrait. One would indeed be hard pressed to imagine this human figure sitting alone in the woods. The interaction between the man and his dogs emerges as social, even psychological: the dogs complete the hunter’s gestures with their bodies, the spaniel that receives his caress even sticking out his tongue in reciprocation, while the turned heads and gazes of the two dogs conjure the effect of silent communication with their master. Both animals indeed manifest carefully observed canine modes of attending to a human companion—unwavering watchfulness and affection-seeking inclination—thus putting the lie to Louis Hourticq’s anthropomorphic formulation that the dogs show “an imploring eye embedded with a desperate desire to speak with the man.”10 Speaking is not at issue in this tableau of physical reciprocity.

Portraits of hunters with their dogs and game had appeared in seventeenth-century English court portraiture as well as Dutch family groups, and the Guilden Cabinet of Corneille De Bie, published in Antwerp in 1661, featured an engraved portrait of Pieter Boel with his hand stroking the head of an attentive greyhound, a possible inspiration for Desportes’s use of the gesture.11 But Desportes’s painting alters the conventions of group hunt portraiture by enhancing the role of the dogs and by incorporating even the creatures recently killed into the ensemble. The artfully piled, still vibrant bodies of the dead animals form a structural and tactile base for the living members of the group, as implied by the spaniel’s foreleg stretched possessively above the other creatures and by the hunter’s corresponding caress.

We can observe the care Desportes took to coordinate his own figure with those of the animals by considering his preparatory chalk study for the painting (Figure 1.2), as well as a preliminary oil that closely follows it (Private Collection).12 Horizontally distributed, the figural group in the earlier works appears more haphazard in its arrangement, an effect increased by the inclusion of a third, more aimless, hound on the right and a horse behind the tree. Gazing downward or off to the side, rather than out at the viewer, and with his right hand gesturing in a vague rhetorical flourish, the bewigged artist appears less involved with his animal companions and with his environment than he does in the final painting. When Desportes shifted the composition of the final painting to a vertical, he integrated landscape, man, dogs, and dead game through a flowing triangle of material agents, subtly enhanced by equivalent spirals in the postures of the hunter and the standing dog. The placement of a gun in the hunter’s gesturing hand also makes him appear more kin to his dogs: we i...