![]()

1

‘Only sissies and women sew’: An introduction

Following the publication of her book, The Subversive Stitch: Embroidery and the Making of the Feminine, towards the end of 1984, Rozsika Parker appears to have given a single press interview. During the course of a short conversation, in response to Parker’s contention that ‘the art of embroidery has been the means of educating women into the feminine ideal, and of proving that they have attained it, but it has also provided a weapon of resistance to the constraints of femininity’, the journalist Anne Caborn asked why there were no men in the book.1 Parker had, in fact, opened the book with reference to men that she had found in a recent government statistics report on ‘leisure activities’ that revealed: ‘Needlework is the favourite hobby of two per cent of British males, about equal to the number who go to church regularly. Nearly one in three fills in football coupons, in an average month, or has a bet.’2 From this both women agreed, somewhat humorously, that ‘real men gamble and fill in football coupons: only cissies and women sew and swell congregations’.3 Writing up her interview Caborn remained struck by Parker’s ‘juxtaposition of needleworkers and churchgoers’ which she thought ‘neatly picks out the unspoken presumption’ that for men needlework of any sort was emasculating and carried the stigma of not just effeminacy but further of homosexuality: ‘Your average hot blooded male is no more likely to whip his embroidery out in a public place, than he is to turn up in the local wearing purple hot pants. Well, it’s not really what you’d call macho. Tough. Is it?’

Caborn drew up a short list of male needleworkers from the well-known (the Duke of Windsor, formerly the Prince of Wales and briefly King Edward VIII) and the obscure (Sir Alec Douglas-Home, 14th Earl of Home and Conservative Prime Minister, 1963–4) to the surprising (Rock Hudson, one-time Hollywood matinée idol), actively and playfully disrupting Parker’s stress on embroidery’s critical role in ‘the making of the feminine’ alone. In reply, Parker pointed out that the issue of men’s erasure from the history of embroidery had actually been, from an early stage, a factor in her thinking. In the 1970s, as part of the Women’s Art History Collective, when Parker first began to reconsider embroidery, she was struck by the prominent position men often held in its history. Embroidery had not always been ‘women’s work’.4 Unlike the similar research being done by contemporary feminist art critics, art historians and artists in America, such as Patricia Mainardi, Rachel Maines, Toni Flores Fratto, Lucy Lippard and Judy Chicago, whose work Parker read and reviewed, she remained perturbed by the fact that the history of needlework seemed to oppress women further by its omission of men.5 Parker had been ‘taught to embroider aged 6 or 7,’ but, she recalled, it was considered too ‘soppy and sissy’ for her brothers who were given toy guns to play with.6

Towards the end of the interview with Caborn, Parker reflected, ‘Why is it that a man impairs his masculinity if he embroiders?’ She was not alone in her thinking. In 1984, as Parker’s book appeared, the American historian Joan Jensen acknowledged that ‘Men have been tailors and factory workers; sailors at sea have sewn their own clothing,’ practices that were related, yet somehow removed, from the realities of women’s experiences of needlework.7 Studies of women’s needlework proliferated in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries but to date there has not been a single book-length study about men and the culture of needlework. To understand better how needlework became so associated with the feminine ideal Parker analysed over a thousand years of its history in Britain. Over the past five hundred years, in particular, she located ‘transitional’ moments when embroidery became a social and economic, as much as a cultural, factor in the separation of the genders into public and private spheres.8 She focused on a diverse range of selected examples taking in the presence of gender in the religious iconography of medieval English embroidery known as Opus Anglicanum, the rise of secular embroidery, domestic sewing and sampler making from the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries, and the industrialization and commercialization of embroidery as well as the expansion of sweated labour and the parallel rediscovery and revival of medieval embroidery’s aesthetics and techniques in the nineteenth century. She concluded her overview with an analysis of the role of needlework in the feminist movements in the opening and closing decades of the twentieth century. Parker noted that in medieval Britain ‘men and women embroidered in guild workshops, or workshops attached to noble households, in monasteries and nunneries,’ but by the Victorian age ‘historians of embroidery obscured its past and instead suggested that embroidery had always been an inherently female activity, a quintessentially feminine craft.’9 As embroidery became feminine it became amateur too.10 ‘Art of course has no sex,’ but craft seemed to.11 Victorian readings of embroidery as an essentially feminine pastime, Parker contested, prevailed unchallenged throughout the entire twentieth century. Within this, she further argued, ‘embroidery and the stereotype of femininity have become collapsed into one another’ yet, ‘paradoxically, while embroidery was employed to inculcate femininity in women, it also enabled them to negotiate the constraints of femininity’.12 If needlework became compulsory in the construction of ‘women’ as a social category, for men the opposite was true. Masculinity became defined through a conspicuous renunciation of needlework yet, predictably, men also retained the privilege of access according to demand or desire.

Concepts of masculinity as a ‘constant, solid entity embedded, not only in the social network but in a deeper “truer” reality’ seemed to resist, and continue to resist, analysis in terms of their construction.13 But men (and certainly their relation to the culture of needlework) were unquestionably shaped by social and economic contexts that fixed genders as stable categories. Parker sees this as happening in tandem with the advent of modern capitalist society after the end of the eighteenth century.14 This is the period in which the term ‘masculinity’ was first used.15 As the Victorians cast women in the role of nature’s needleworker, men were erased from its history. If we know that men stitched during medieval and early modern history, what, from the nineteenth century onwards, compelled Parker to claim, ‘few men would risk jeopardising their sexual identity by claiming a right to the needle’.16 Although Parker pays no attention to ‘cissies’ beyond the first page of The Subversive Stitch, gay men, in particular, have taken up needle and thread for its ‘queer’ subversion of the homophobic and heterosexist policing of gender and sexual identity.17 Indeed, Parker and Griselda Pollock noted in Old Mistresses (1981), one of their major collaborations and very much a prequel to The Subversive Stitch, that once the masculine ideal was obliterated from embroidery’s history ‘it continued to be stitched by queens’.18

The examples of sewing by men, that Joan Jensen included in her study of needlework, draw on what could be called homosocial spaces, all-male arenas in which women are absent, where, it is believed, men’s interest in needlework grew purely out of necessity. If then, as Jensen argues, and Parker concurs, ‘Art. Meditation. Liberation. Exploitation. Needlework has been all these to women,’ what, if anything, has it meant to men?19 Jensen, like Parker, pressed the point that women’s needlework could be a source of pleasure as well as oppression. Women, she noted, could take great pride in their work: ‘whether for sewing on buttons or for taking the fine stitches that created the great women’s art of quilting’.20 For Parker ‘all embroidery’ has a capacity to offer ‘comfort, satisfaction or pleasure for the embroiderer’.21 Yet, when men stitched it is generally understood in terms of practicality over pleasure. Mary Beaudry in her more recent study of the ‘material culture of needlework and sewing’ makes brief reference to the sewing skills of tailors, as well as merchant seaman and working-class boys, but contends that such sewing was motivated ‘both by necessity and for pleasure’.22 Yet, labour over leisure, employment before enjoyment, forms the subtext of any man’s needlework so as to not imperil his fragile masculinity by calling it into question through too close an association with the feminine.

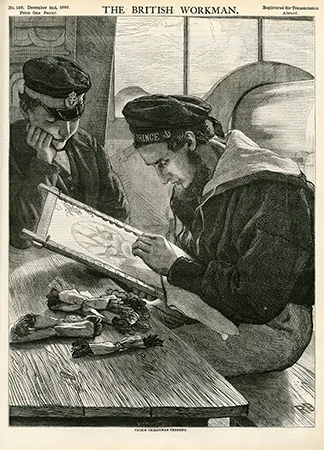

Embroideries by sailors, one of the best-known types of needlework by men, have been dated by historians to c.1840–1900, the very period when embroidery became enduringly wedded to stereotypes of idealized femininity.23 Yet, as Bridget Crowley argues, for sailors, ‘their growing status as folk heroes apparently survived any accusation of “unmanliness” consequent upon this activity.’24 Hypermasculinity, then, could actively negate the feminizing associations of needlework. Victorian representations of the masculine labouring body, especially those of working-class men such as sailors, tended to emphasize male power through physical spectacle. Paradoxically, one of the few known images of a sailor embroidering, published in 1867 in The British Workman, a Victorian Temperance periodical aimed at the working classes, challenges this conventional conceptualization of Victorian idealized manhood (Figure 1.1). The sailor, in this wood-engraving, is posed like Parker’s archetypal female embroiderer in a Victorian drawing room: ‘eyes lowered, head bent, shoulders hunched’.25 Equally he seems to embody Parker’s equation of embroidery and enjoyment. In this vein, Crowley has further argued that ‘the tradition of sailors embroidering for pleasure while at sea was strong’ and ‘just as the sedentary, confined life of the middle-class Victorian woman is reflected in the static representations and minute stitches of her craft, so the characteristics of life at sea are reflected in the work of the seaman’.26 Like Crowley, Janet West suggests that sailors probably used materials that were produced for domestic consumption and may well have shopped for Berlin wools.27 The sailor in this engraving is working a kit (which looks like a version of the popular Berlin woolwork ‘birds of paradise’ design), complete with the pre-designed canvas stretched in a tambour frame, with packs of wool on the table.

Figure 1.1 ‘Jack’s Christmas Present.’ The British Workman, no. 156 (2 December 1867): 141, © The British Library Board (LOU.LON 23).

A group of surviving embroideries by an English sailor, Capt. Garrison Burdett Arey, are known to have been made from ‘paper patterns’ using popular Berlin wools. One depicting a Bird of Paradise (c.1865–9) (Figure 1.2) is strikingly similar to many of the designs sold to middle-class women, in the mid-late nineteenth century, for stitching at home. But another design by Arey, Jesus Blessing the Children, was apparently made after a painting he saw in Paris ‘without any formal pattern or design’.28 Clearly Arey, who also painted (more conventional images of the ships on which he served), had artistic ambitions with needle and thread. Even so, there remains a resistance to accepting the relationality between the image of the embroidering Victorian housewife/damsel, explored by Parker in her book, and that of the hypermasculine sailor. The survival of Arey’s embroideries is unusual as men’s needlework generally goes unrecorded and uncollected. Few museums and galleries hold examples. Such embroiderers are, in terms of public display and discourse, not so much on the margins as beyond them. When an embroidery by a man surfaces it tends to be seen as completely unique.

Figure 1.2 Capt. Garrison Burdett Arey, Bird of Paradise, c.1865–9, woollen yarn on canvas, 21.5 x 27.5 in. (54.6 x 69.8 cm), Courtesy of the collections of the Museum of Old Newbury.

Most people would agree that the feminine culture of needlework, seen to embody a set of binarized clichés (soft, domestic, submissive, amateur), is wholly irreconcilable with masculinity, as defined by its own set of clichés (hard, social, virile, masterful). But this assumes all men are the same; that masculinity as a dominating hegemony is homogeneous.29 An example might illustrate the problem inherent in such assumptions. In the 1990s the American artist Elaine Reichek, one of the most influential embroiderers of modern times, embarked on a body of work that reflected on ‘men who sew’.30 Reichek’s Sampler (Hercules) (1997) brings together images of once-celebrated male embroiderers from history (Plate 1). At the centre is Hercules, the personification of heroic masculinity from classical mythology to today’s popular culture (Disney released its Hercules animat...