![]()

1 CRITICALITY

For Rogers, one of the most important aspects of being a modern architect was to exercise a critical understanding of, and a creative response to, reality and the challenges of artistic practice. The architect, according to Rogers, cannot be satisfied with just developing a good project, as professionally sound as it may be: there is a moral obligation to put her/his skills, creativity, and intelligence to good use for the advancement of the art, the meaningful shaping of the environment and the betterment of society.

The seeds for his notion of criticality were already planted in the young Rogers during his formative years at the Politecnico in Milan through the teachings of one of his professors, Ambrogio Annoni, not on modern architecture per se—which at that time was still struggling to make its way through the school’s conservative environment—but on preservation. While Rogers and his fellow classmates Banfi, Belgiojoso, and Peressutti did not learn much—with few exceptions—from Politecnico’s conservative, historicist faculty, essentially going through a self-directed education, sensitive to what was happening in Northern Europe in the 1920s, the teachings of Annoni had a lasting impact. What characterized Annoni’s theory about preservation was the so-called “case-by-case” approach, whereby the architect has to exercise her/his best judgment, through rational method and artistic sensitivity, while tackling the problem at hand without preconceived ideas or ideological strategies about what and how to preserve. This was in stark contrast with the leading preservationist of the time, Rome-based Gustavo Giovannoni, who preached an ideologically rigid approach to the preservation of historic structures and urban organisms, in addition to an ideological opposition to modern architecture.1 For a case-by-case approach, which Rogers and his professional partners at BBPR followed later in their career when they were given commissions involving historic fabrics—but also more in general for any project—the exercise of critical judgment was crucial. However, it had to be supported by a rigorous method of analysis, alternative options evaluations, and a creative process: a method similar to the one that was at the foundation of the Modern Project in architecture, as symbolized by Corbu’s famous dictum “Architecture is a well-posed problem.” Architecture became a problem that could be rationally defined without preconceptions, critically evaluated through a rational method and creatively resolved as a critique to consolidated stereotypes.2

Rogers’ process of self-education included an intense study of the most advanced research going on at that time in France, Germany, Austria, and Russia, and among the many lessons that he learned from the pioneers of modern architecture was the critical mentality that would serve him and his partners well in their later career. As Rogers later observed, while interrogating himself about the common denominator of Corbu’s manifold research, geared at envisioning—beyond stylistic formulas—whole new dimensions and manifestations of modern living as critiques of consolidated cultural patterns,

Le Corbusier’s first act is a complete rejection of consolidated models, not only in terms of forms, but especially in terms of the contents that determine those forms. More than an inventor of original forms, he is an inventor of “worlds”: the world of those who dwell, the world of those who co-habit within the city, the world of those who work in the countryside, the world of those who retreat to pray in a church or in a convent. The world, finally, of those who need care in a hospital.3

Beyond important figures within the field of architecture, recent—such as Loos, Van de Velde, Gropius, and Le Corbusier—and more distant—such as Leon Battista Alberti—Rogers also found inspiration to form his own critical sensibility in other protagonists of Italian culture and society, such as philosopher Enzo Paci and industrialist Adriano Olivetti.4 We shall discuss the relationship between Rogers and the former in a later chapter, but here we should dwell on the relationship with the latter, because it also relates to the BBPR’s first important “critical” work.

The Valle d’Aosta Master Plan

Enlightened capitalist, man of great culture, combining innovative business vision with a genuine humanitarian spirit, Adriano Olivetti belonged to the second generation of a legendary Italian industrial dynasty, initiated by Adriano’s father, Camillo. Rogers, twenty-five, and Adriano Olivetti, thirty-three, met in Trieste—Rogers’ hometown where he continued to return frequently—in 1934 to discuss a possible commission for the young firm of BBPR—just graduated in 1932—and other Milanese professionals: a regional master plan for Italy’s north-westernmost region of Valle d’Aosta. Olivetti’s factory—at the time producing typewriters, based on Camillo’s notable 1930 M40 model—was located in Ivrea, a small town north-east of Turin, just at the foot of the Alps, and along the river Dora Baltea that runs from the Valle d’Aosta to the south of the Po Valley. Olivetti understood that Ivrea’s potential for growth was also related to the growth of its hinterland, consisting mainly of the Valle d’Aosta, hence his interest in launching a comprehensive regional plan for the economic and social development of that region.

Far and logistically secluded from the more developed areas of industrial Northern Italy—notably the industrial triangle of Turin–Milan–Genoa—the mountainous territory of the Valle d’Aosta was suffering from poverty, lack of economic development, and weak infrastructure. Nevertheless, the valley boasted spectacular natural environments—e.g., the Mont Blanc and the Cervino/Matterhorn mountainous groups—that needed only to be exploited for tourism. Olivetti had the vision to unlock the valley’s untapped potential. However, he did not see just an opportunity for economic growth, as he also cultivated a genuine humanitarian concern for people’s living standards. Certainly influenced by his father Camillo’s inclination toward a moderate form of “socialism”—in addition to his own vague initial fascination with fascist “corporativism”5—Adriano had a vision for community development and a humane approach to industrial growth that benefited from architecture and urbanism. As Rogers recalled many years later in his passionate commemoration of his dear friend Adriano,6 the Valle d’Aosta Master Plan, beyond its own value as a regional plan, was the embodiment of Olivetti’s philosophy: politics, social reform, economy, and urbanism converging together toward an idea of civic growth. In his foreword to the master plan document Il piano della Valle d’Aosta, Olivetti outlined his clear vision: “The plan wanted to show how, going beyond traditional and limited models, a modern state could change a region where there is a need of renewal and environmental recovery, to bring it back to its entire social and human dignity.”7

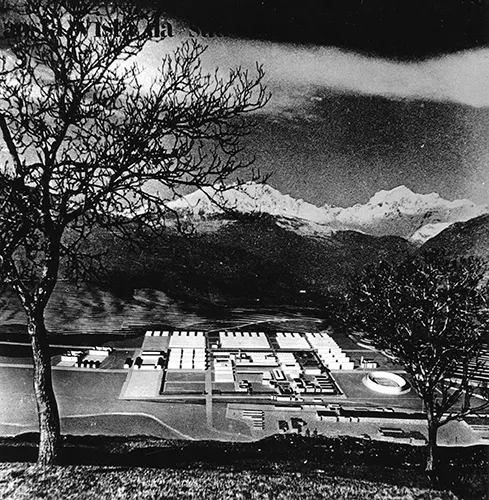

FIGURE 1.1 BBPR, Piano per la Valle d’Aosta (1934–36), urban design plan for the city of Aosta by Banfi, Peressutti, and Rogers. © BBPR, courtesy of Alberico Belgiojoso.

Completed in 1936—when it was exhibited at the IV Milan Triennale—and officially and fully presented in 1937 in Rome, the plan, whose team included, as architects/planners, BBPR and already experienced and recognized professionals such as Piero Bottoni, Luigi Figini, and Gino Pollini, consisted of a massive set of 450 boards (150 x 50 cm) and five models. In its introductory part, the plan offered an analysis of natural assets, geography, history, demographic trends, economy, social characters, infrastructure, and tourism. The master plan also included more detailed plans for the Italian area of Mont Blanc—by Figini and Pollini—the Breuil Valley—by Belgiojoso and Bottoni—the city of Aosta and the tourist center at Pila—both by Banfi, Peressutti, and Rogers—and a new residential neighborhood in Ivrea—by Figini and Pollini. For each of these detailed plans, the urbanistic and architectural vision rested on a thorough analysis of geography, agricultural activities, land-ownership, existing housing conditions, demographics, and economic strengths and weaknesses. One of the team members, Piero Bottoni, proudly considered the plan “the most comprehensive regional plan developed so far in Italy and probably in the world.”8

As exemplified in the vision for Aosta by Banfi, Peressutti, and Rogers, the proposal advanced a critique of current conditions and development models, to suggest a new modern environment in a harmonic dialog with nature. The refined and balanced fabric of abstracted, modern volumes was tempered by a clear, though veiled and subtle, historical reference to Aosta’s Roman history, with the new stadium situated the way a Roman amphitheater would have been located in a typical Roman new town. The 3D urban design interpretation of a 2D larger planning strategy, aligned with the most advanced experimentations by Corbu and other Northern European architects and planners, was also a critique of traditional disciplinary tools and modes of operation.

Rationalism of the 1930s

The critical approach that BBPR manifested in the Valle d’Aosta large-scale planning work was also taken for their initial architectural design challenges. BBPR fully engaged in the fervor of urban renewal and new construction pursued by the fascist regime, taking a political alignment with the Fascist National Party that Rogers and all the others, in hindsight, deeply regretted. Rogers did not shrink to comment on various occasions about the mistake they made, along with many other artists and architects—namely, the most distinguished of all, Giuseppe Terragni—who had embraced the fascist ideology. Rogers recalled that “through egocentrism, we posited absurd syllogisms, such as the one that went: Fascism is a revolution, our art is revolutionary, therefore Fascism will have to adopt our art.”9 In fairness, the fascist regime maintained a rather ambiguous position toward cultural and artistic movements, mostly encouraging rhetoric and monumental revivals—and increasingly so through the years—but also supporting modern experimentations, such as in the fortunate case of the competition for the new railway station in Florence (1932), won by Giovanni Michelucci’s team. As Palmiro Togliatti, who eventually became the post-Second World War leader of the Italian Communist Party, already noted in 1935:

What do we find in the Fascist ideology? Everything. It is an eclectic ideology … an exasperated nationalist ideology … [but also] fragments of social-democratic models … organized [controlled] capitalism … and from communism: planning, etc. The Fascist ideology contains a series of heterogeneous elements. We need to keep this in mind, because it allows us to understand what this ideology is functional for.10

This contextual extenuation notwithstanding, the painful mistake remains, especially when compared with the few artists and intellectuals, such as Edoardo Persico, who saw the real nature of the regime from its early years and instead maintained a firm and ethical stance of opposition.

In spite of their political blindness toward the fascist regime, BBPR continued to cultivate a working method that led them to grow a body of work that Bonfanti and Porta did not hesitate to call “critical architecture.”11 Already in the mid-1930s, they took part in several national design competitions, the first important being the one in 1934 for the Palazzo del Littorio in Rome, the new headquarters of the Fascist National Party on via dei Fori Imperiali, in the midst of the archeological district of the Roman Fora. More than 100 teams participated, seventy-two were selected for a public exhibition, and twelve for a second phase of the contest. BBPR, with Figini and Pollini, and engineer Arturo Danusso—who several years later would consult with BBPR for their landmark work, the Velasca Tower in Milan—developed a project with a clearly modern vocabul...