![]()

WATER AS SACRED

![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Water—A Living Spirit

Miguel A. De La Torre

That the Iliff School of Theology held its inaugural Ecojustice conference on the intersection of water and environmental racism during the fall of 2019 is apropos; after all, Iliff, founded in 1892, exists because of the commodification of the water. The school’s namesake, John Wesley Iliff (1831–78), greatly profited from the imposition of a Eurocentric worldview that saw natural resources, like water, as a commodity to be exploited for personal economic gains rather than a living sacred entity. While fortune seekers, known as the “Fifty-niners” traversed what they observed to be the wastelands of the Colorado plains to reach the Rocky Mountains where they prospected for gold, Iliff—the man, not the school—saw an opportunity. Originally born in McLuney, Ohio, he headed west with $500 in his pocket, arriving in Denver in 1859. Rather than mining for riches, he found riches in mining miners. From his general store off Larimer between F and G Streets, Iliff provided the goods miners needed to stake their claims. By 1861, he began buying land along the South Platte River for his emerging cattle ranch. He discovered undernourished cattle, cheaply bought, could easily be fattened if allowed to graze, increasing their economic worth. After 1868, Iliff was providing beef to the Union Pacific and Colorado Central Railroad crews, army forts, the Cheyenne boom-town, the Chicago Stockyards and several Indian reservations.1

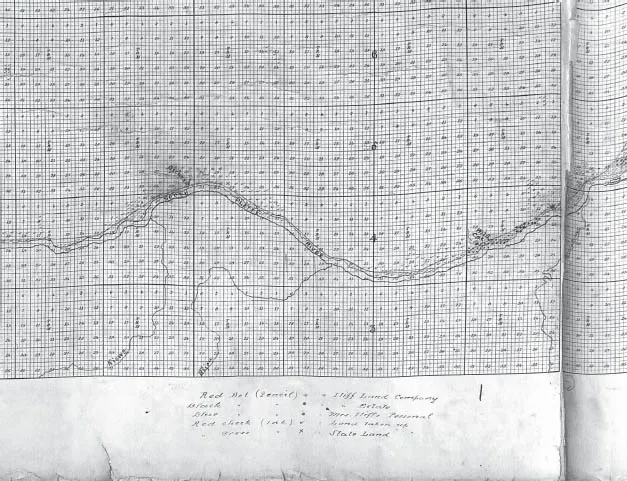

His holdings were so vast that his cattle grazed over 650,000 acres. He did not own all this land; what he owned was the water rights. Manipulating the Homestead Act (contrary to the original intent of the US Congress), Iliff was able to control water rights between Julesburg and Denver. Owning the water is what made the land useful for other ranchers and farmers.2 Because Iliff was the first person to divert water for a beneficial use, he acquired sole rights to the water. Taking advantage of the doctrine of prior appropriation, which was based on the legal concept qui prior est tempore potior est jure (the one who is first in time is first in right), Iliff gained perpetual legal rights to the South Platte’s flow of water along with its streams and offshoots.3

FIGURE 1. Hand-drawn cloth map of land John Wesley Iliff controlled along the South Platte River (Margaret E. Scheve Archives and Special Collections, Iliff School of Theology, Denver. Photo by Erin Shafer)

A monopoly on water meant that no one could homestead between his lands without purchasing water directly from him. Water is what made land—private and public—valuable, and because he owned the water, he was able to create a cattle empire. His cattle grazed on so-called public land (land still belonging to the indigenous people) because he provided the water that made the land grazable. Iliff’s raising of cattle would contribute to the devastation of the local bison. He was among those who within two decades participated in driving the buffalo to near extinction, reducing the numbers south of Canada to 325 and replacing them with about 5.5 million cattle, allowing him to be among the first to earn the sobriquet “cattle king.”4

An Indigenous Worldview

Iliff has been portrayed as a visionary, a seer of the future. He gazed upon grazable empty land not being maximized for profit and, by taking control of flowing water, made a fortune that has directly benefited the author of this chapter, who serves as a tenured professor at the institution his family founded. Iliff’s fulfilled a manifest destiny, a worldview that credited his Methodist God for richly blessing him for his faithfulness. But there exists another worldview that questions whether anyone can own water; for water is alive and upon it all life depends, not just humans who eat the cattle, but the cattle who eats the grass, and the grass itself. Smohalla of the Wanapum, a different kind of seer, asserted in 1890:

You ask me to plow the ground. Shall I take a knife and tear my mother’s bosom? Then when I die she will not take me to her bosom to rest. You ask me to dig for stone. Shall I dig under her skin for bones? Then when I die I cannot enter her body to be born again. You ask me to cut grass and make hay and sell it, and be rich like white men. How dare I cut off my mother’s hair.5

Cognizant of the violence in placing words into someone else’s mouth, I nevertheless wonder if Smohalla would have also agreed with the imagery that hoarding water for the gains of one person would be similar to draining the blood from one’s mother’s veins?

Indigenous scholar George “Tink” Tinker reminded me during a conversation that within the North American indigenous worldview, the river, the spring, and the lake all have their own living being. In his own tradition, the Osage word for river is ni. Every ni, according to him, is a person, alive, and a close relative on whom our lives depend. As such, they are due the respect granted to any human being. Contrary to the Eurocentric worldview embodied by John Wesley Iliff, which saw bodies of water as commodities needing to be exploited for personal enrichment, indigenous people recognized these bodies of water as life. For example, the Overhill Cherokee of what is today eastern Tennessee knew the Little Tennessee River as Yunwi Gamahida, translated as the long Man, “a living being who granted energy and spoke to those who knew how to listen.”6 The Taos Pueblo Community, in what is today called New Mexico, understood that their earliest ancestors emerged from the cold waters of Ba Whyea (Blue Lake); and into these waters “the dead return, to become spirits, known as ‘the ones who always believe’ [where] they merge with cloud people, the rain-bringing Pueblo Indian spirits known as Kachinas.”7

In what would become Central America, the Aztec cosmology includes Chalchiuhtlicue (She of the jade skirt), the goddess of rivers, lakes, streams, and other freshwaters; wife (or sister) to Tlaloc, the god of rain. She is associated with fertility and is responsible for bringing forth maize, the life source of the people. There is also a goddess of saltwater, Huixtocihuatl, a fertility deity. The indigenous worldview of the Américas is not simply some quaint way of understanding water; rather, such an understanding resonates with other indigenous groups throughout the world. Take, for example, the Yoruba people of what today is called Nigeria. They, too, see rivers and streams as a living entity called Oshún, patron of love and eros. Oceans are under the domain of Yemayá, who is associated with womanhood and motherhood. Inle is associated with the fertility of water to produce crops. And Olocun, considered the queen of the ocean’s depth, is responsible for the worldwide flood.8 Likewise, we can look to Asia where China’s Yellow River, one of the world’s major water arteries, deity is Hebo, who like the river is “benevolent [yet] greedy, unpredictable and dangerously destructive.”9 Or we can look to the sacred Ganges River of India, the holiest of all Hindu rivers, synonymous with the goddess Gaṅgā. Her waters are the “liquid embodiment of śakti [female principle of divine energy] as well as the sustaining immortal fluid (amrta) of mother’s milk.” To bathe in her waters facilitates liberation from the life-and-death cycle (moksa).10 Even European indigenous peoples, prior to the imposition of Christianity, recognized the sacredness of water, whether they be the Celtic people of Ireland who knew the River Boyne to be the goddess Boann; the Welsh who looked to Llyr, god of the sea; or the Gaul who recognize the River Seine as the goddess Sequana.

If indeed the worldview of the majority of the earth’s indigenous peoples are closer to reality than the Eurocentric neoliberal worldview which is rooted in the colonizing capitalist philosophical trend rooted in Christianity and the so-called Age of Enlightenment, then to own water becomes a form of enslavement, not just of the living entity associated with water, but upon those who depend on the water. To impose the Eurocentric worldview upon the planet’s inhabitants extends a global oppression which enriches a minority of the global population while creating the illusion of white supremacy which confuses unearned riches from natural resources with advanced civilization. Once water is stripped of its spiritual entity and reduced to a commodity, it can be manipulated to benefit the global minority at the expense of the global majority.

A Eurocentric Worldview

Rather than recognizing water as a living entity, Western religions like Christianity have focused on the relationship established between humans and what they perceive to be the one true God. Based on this human-divine relationship, intra-human relationships are established, which usually are portrayed as positive for those who share one’s beliefs or negative toward those with a different worldview faith tradition. Missing from the Christianity of the colonizers has been any interconnectedness with a collective or communal spirituality linked to water. Emphasis, among many Protestants, usually is tied to some “personal” relationship with Jesus. Little attention is given to the relationship between humans and other spiritual entities.

If creation stories describe humanity’s appointment as stewards of the earth’s resources, then human beings as caretakers are called to protect, preserve, and safeguard these living resources so all can benefit and enjoy its fruits. Creation as gift means all that is living has basic rights, one of which is that no person or group has the right to hoard the earth’s resources. Hoarding the earth’s resources upsets the delicate balance between life and those dependent on said resources to sustain life. Ironically, Christianity has encouraged the destruction of creation. The first creation story found in the Hebrew Bible ends with: “And God said to [human beings], ‘Be fruitful and multiply, and fill the earth and subdue it; and have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the air and over every living thing that moves upon the earth” (Gen 1:28). Biblical passages such as these led to and justified human domination and ownership of nature, specifically, the water and the land. Christians have come to read this verse as permission to use and abuse creation, similar to how the ancient rulers once used and abused their subjects. Man (and here I mean those who are m...