![]()

1

INTRODUCTION

Rebecca Enlander and Victoria Ginn

This introductory chapter consists of two parts. In Part I we begin to define what identity means to an archaeologist, and to consider the visibility of identity constructs within the archaeological record. In Part II we present a short case study in which we explore the creation and maintenance of identities within the Atlantic roundhouse tradition.

Part I: Locating identity

‘The archaeological record is made up of, among other things, the direct and indirect results of countless individual actions’ (Johnson 2004, 241). It can be questioned whether or not we can relate the results of these actions, i.e. the archaeological remains, to the intentions and identity of the people who carried them out. This chapter and the following chapters presented within this volume do not claim to re-address the legitimacy of exploring past identity. Rather, they explore tentatively the identity potential of various elements of the observed archaeological record, including domestic and ritual architecture, material culture, mortuary sites, and human remains. They succeed in providing a narrative for the identification and investigation of identity in the archaeological record, and the tangible facets of those identities that can be drawn out.

Definitions of identity

The term identity is defined as ‘The quality or condition of being the same in substance, composition, nature, properties, or in particular qualities under consideration; absolute or essential sameness; oneness’ (Oxford English Dictionary). It has been used most frequently in archaeological literature in reference to ethnic and cultural identity. Traditional perceptions of identity – made prominent by the writing of Childe and others – view it as a construct which is objective, and socially inherited. In this early history of archaeology, the identification and classification of organising principles of wider historical processes, or grand narratives, dominated the discipline through the establishment of distinct typologies and chronologies. Jones and Graves-Brown (1996, 1) emphasise that ‘questions of identity often come to the fore at times of social and political change’. As such, it is unsurprising that an archaeological concern with the actions of individual humans and their identities is a relatively recent phenomenon which arose – in its European context – after the collapse of the Soviet Union and the associated political turmoil of the 1990s. It is only with post-processualist, thematic approaches to gender, age, ethnicity, status, and occupation that questions about the identity of our predecessors, as observed archaeologically, have truly come to the fore. There has ensued an increasing scepticism of the importance placed on objective, all-encompassing cultural definitions of identity. For instance, Jones stresses that group identity is multi-dimensional (1997; also Jones and Graves-Brown 1996, 5), while Díaz-Andreu and Lucy (2005) emphasis potentially subjective and multi-natured identities on an individual and collective scale.

Since the 1990s, the archaeological perception of ‘embodied’ and plural facets of identity such as gender, sexuality and age have seen increased emphasis. The publication of volumes including ‘Engendering Archaeology: Women and Prehistory’ (Gero and Conkey 1992) and ‘Invisible People and Processes: Writing Gender and Childhood into European Archaeology’ (Moore and Scott 1997) led to an acceptance that gender identities and sexual roles are not necessarily dualistic or universal, but are transformed and influenced during our lifecycles. Biological identity is arguably more tangible and has seen increased emphasis, but the identity metanarrative is often simply ignored; for example, ‘identity’ does not appear in the index of Whitley’s edited 1998 volume Reader in Archaeological Theory: Post-processual and cognitive approaches.

The increasing unease with an identity which is applicable to prehistory, particularly to prehistoric individuals, may be intrinsically linked to the development of agency theory, and its, at times, liberal application of free-thinking agents to the ancient past. In agency theory, knowledgeable agents act with intentionality upon the world around them and with other agents; their actions are not limited by social structure. On the other hand, a person’s individual actions are usually constrained by those of other individuals, and are thus, to some extent, the products of the community. Agents, therefore, may not always be ‘free’ and the impact of power relations needs to be considered. The possible overemphasis of the role of ‘free’ agents in past processes and events has, in part, been caused by the comparative neglect of themes like the identity of status rarely moving beyond the premise of exchange and power (Díaz-Andreu and Lucy 2005, 5; Meskell 2002, 284; although refer to Brück 2001 and Grogan, this volume). Challenges by Thomas (2008: in response to Knapp and van Dommelen 2008) to the ability of acknowledging autonomous individuals in prehistory for instance, warn that imposing central agents on the distant past plays to modern western constructs of free individuals, and is in danger of producing an ‘ethnocentric distortion’ of the past (see discussion in Knapp and van Dommelen 2008; also Thomas 2000 regarding the individual in Neolithic mortuary contexts).

However, post-structuralist models of agency are socially defined against a backdrop of particular historical situations whereby people act within the ‘historically situated agency’ of their circumstances (Robb 2010, 499). Agents operate in a landscape of socially mediated values, the terms of their own individual identities (or self-hood), and relationships and social exchanges with other agents and culture. Such a definition of socially constituted persons which combines self-perception, relational identification, as well as intentional and unintentional actions is not considered an intrusive persona by the current authors, whether identified at an individual, multiple or communal scale. Robb (ibid.) goes beyond the ‘autonomous individual’ and, just as identities can be multiple, contested and redefined during a person’s life course, he proposes multiple and collective agencies. Individuals can participate in distinct forms of collective agency and will adopt and modulate their actions consciously and unconsciously to best fit any given situation. ‘It follows that a key parameter of how people construct their agency…is their understanding of the relations with others; this is true whether these other entities are understood as individual persons or groups’ (ibid., 503–4).

Computer simulation, although not used within this volume, provides an exciting avenue for the exploration of the actions of individual agents based on biological or economic theory (Graham 2009; Graham 2006; Lake 2004). Explicitly concerned with individual actions, agent-based simulations help move the landscape beyond mere distribution maps. It is a theoretically attractive methodology due to the combination of individual agency and whole society modelling, but also one that frequently comes under criticism for not reflecting the potentially irrational behaviour, subjective choices and complex psychology exhibited by human beings.

Visibility of identity

As Robb’s framework suggests (above), under appropriate circumstances and armed with a theoretically informed and appropriately rigorous methodology, the analysis of ‘historically situated’ identity constructs is not an impossible task. There are, of course, limitations which must be recognised. With regards to the application of cognitive approaches, Flannery and Marcus (1998, 46) warn that ‘when almost no background knowledge is available… reconstruction can border on science fiction. That is when every figurine becomes a ‘fertility goddess’ and every misshapen boulder a ‘cult stone’’ and this rings just as true for identity. So how do archaeologists begin to attempt to recognise and analyse a concept that is constantly invented and reinvented, is multiple and contradictory, represents a continual process of narration, and is susceptible to elaboration and even fictitiousness?

The attribution of cultural identity to material remains has a long and well-established history. Observing similarities and distinctions within past material culture – whether diachronically, synchronically or geographically – is perhaps the most common approach, and has certainly been used frequently throughout this volume (see also Díaz-Andreu 1996; Hides 1996; Thurston et al. 2009). However, the relationship between material culture and identity is complex, especially with regards to the boundaries of ethnic difference (Jones 1997). While ‘material and environmental conditions clearly have a role to play in creating the opportunities for similarities to develop… they explain nothing in themselves – it is the cultural and social world of individual communities that take on a recognisable character’ (Henderson 2007, 302).

Individuals, groups and societies are not simply passive victims of their identities. Instead, they continuously articulate and elucidate self-conscious definitions of identity which fluctuate over time. Archaeologists often prefer to examine these identities, and their dynamic nature, through extant material culture. By constructing spatial patterns of local and non-local material, and by analysing diachronic alterations in that material archaeologists hope to construct an idea of the collective ‘Self’ and ‘Other’ (see e.g. Pérez and Odriozola 2009, 266). The assumption that archaeologists can analyse varying patterns in material culture to shed light on identity constructs has forged the long-prevailing notion of chronological identity. Recent large-scale, Bayesian-orientated research projects, such as those on the Mesolithic–Neolithic transition in Britain (Griffiths 2012; Whittle et al. 2011), warn against the enduring associations between chronological periods, material and identities, however. Spatially and temporally discrete distributions of material culture are themselves not a reflection of bounded groups. A one-to-one relationship between cultural identity and similarities or differences in material culture cannot be assumed. Instead, archaeologists should conceptualise identity as self-defining, and as actively communicated through processes of manipulation of both economic and political resources (Jones 2007, 113).

Political identities

The chronological association between questions concerning the identity of past people(s) and contemporary political, social or economic uncertainty was highlighted above (also Jones and Graves-Brown 1996, 1). Meskell notes that ‘relationships with particular historical trajectories, nostalgia and commemoration, and… the forceful materiality of archaeological remains’ were sparked during the major political restructuring and consequent upheavals seen in the Soviet Union. His comments occur in a general discussion of archaeological approaches to cultural identity in the twentieth century, and he warns more generally that ‘cultural heritage has been deployed in quests for specific modernities, sometimes at the expense or erasure of others’ (2002, 288). Commentators with politically fuelled agendas, such as those cases described by Meskell, often use the collective memory to lay claim to past life experiences and places of significance. This process is at the expense of more encompassing, cultural narratives which accommodate multiple identities and consensual histories, and is especially prevalent in colonial contexts (ibid., 292). Specifically, nationalist archaeologies have seen the manipulation of ethnic identities for political gain, a theme which is discussed by Popa (this volume) in reference to Romanian identity constructs. However, it is precisely these archaeological landscapes that hold the potential to contribute to wider narratives of social memory and national identity: as archaeologists we are privy to the materiality of contested landscapes of the past (ibid.).

The identity of place

Identities have long been perceived as linked to and correlating with specific geographical locations. Spatial computational modelling is becoming increasingly popular as an analytical tool, especially with the widespread availability of the push-button Geographic Information System (GIS) capabilities. The use of a GIS can enable a new perspective into the spatial dimension of human culture, into the ways in which place-based community identities have been represented in spatial form in the landscape, and it can also facilitate the analysis of how identity was actively created and renegotiated. The particular archaeological nuance of a specific landscape helps to define its identity, or at least its sameness and/or otherness compared to different landscapes. Of course the identity of a landscape is also porous and mobile: ‘What a geographical location means to any group of people changes as its history is told and retold, and the meaning is no more stable than identity itself, therefore, places are constituent parts, but also products, of identity’ (Sokolove et al. 2002, 25).

There has also been a tacit acceptance of ‘modern political boundaries as a framework for the analysis of the past’ (Jones and Graves-Brown 1996, 12) which a GIS can both hinder and help to overcome. The current authors used a GIS to analyse Irish rock art and Bronze Age settlement patterns in Ireland as part of their respective research. Both authors anticipated that modern political boundaries would not be able to force the acceptance of specific analytical boundaries as the island of Ireland itself provided a convenient geographic entity for study. However, the border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland created immense difficulties in aligning differentially developed datasets (such as soils, rivers and watersheds) within the two countries.

Part II: Scales of identity

In the remainder of this chapter we will use the roundhouse tradition in Atlantic Scotland as a setting to explore the creation and maintenance of local and non-local identities.

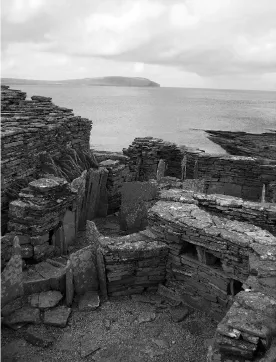

In addition to extant material culture (as highlighted above), monumental architecture is perhaps the most enduring and readily accessible relic of past societies. Atlantic Scottish roundhouses, and particularly nucleated broch settlements of the Iron Age, embody some of the finest examples of prehistoric architectural engineering in Europe (see Figure 1.1). In this domestic arena the themes of architecturally defined space, spatial ordering and structured deposition are brought together in order to narrate the visibility of local and non-local identities. Social organisation in past societies is evident through actual architectural boundaries or, more subtly, through the separation of daily tasks which may leave distinct zonal remains. Such expressions can be used as a tool in the exploration of identity, specifically the identity of those that shaped, and were shaped by them. Socially mediated identity, constructed through the application of spatial ordering, is particularly demonstrable in Atlantic roundhouses.

Architecturally defined space

Atlantic roundhouses emerge c. 600 BC (Hedges 1987, 117), are characterised by their massive dry-stone walls, and represent a radical departure from the previously encountered cellular settlement types. Some examples are rather complex and have the addition of guard cells, intra-mural cells and stairs, and scarcement ledges. These complex roundhouses are generally isolated and essentially self-sufficient units in the Western Isles and Shetland, but can also be part of clustered village settlements in Orkney, such as Howe of Howe (Ballin Smith 1994). A broch is a specialised form of complex roundhouse, identified by a discernible upper floor. Central brochs were occasionally surrounded by roundhouses and complex roundhouses which formed a broch village.

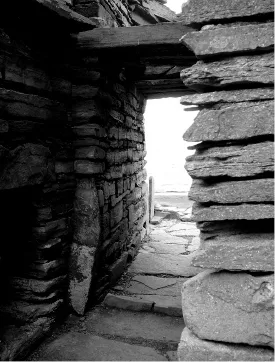

These three types of domestic dwellings all share a specific architectural trait: the control of movement within their confines. Sally Foster (1989) applied access analysis – a technique based on Hillier and Hanson’s 1984 Gamma analysis – to broch village architecture in Orkney and Caithness. She demonstrated how the builders might have deliberately designed ways in which movement into, and within these houses was controlled. This would have resulted in marked differences in how local and non-local residents of the area might have perceived the buildings. To an outsider, a central broch tower and a sea of tightly packed roofs of the surrounding buildings may have seemed intimidating. Movement through the village was often controlled by the creation of a narrow passage through the other structures, passing spaces in which strangers could not freely interact. This passage was frequently aligned with the entrance to the central broch tower, and would have acted as a marked transition from the outside world into the centre of the village. This passage also mirrored the entrance to the central broch itself: a tunnel-like passage which was probably marked (Foster 1989, 232–3 and Armit 2003, 105. See also Figure 1.1). This restrictive architecture of broch formation embodies an explicit physical boundary, in effect creating a powerful distinction between inhabitants and outsiders.

Figure 1.1: Mid Howe broch village, Rousay, Orkney. Remains of the low, passage entrance int...