![]()

1

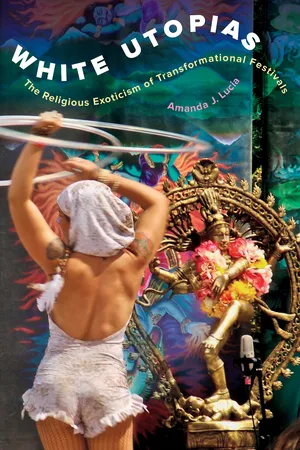

Romanticizing the Premodern

The Confluence of Indic and Indigenous Spiritualities

Opening Kali fire ceremony with Sundari Lakshmi

Thursday, May 25, 2014

Shakti Fest, Joshua Tree, California1

Sundari Lakshmi was in the center, her long, natural hair pulled into a low ponytail. She wore a black sari and a microphone headpiece. She was soft-spoken. She was probably forty-five years old, a Caucasian woman. Her Sanskrit seemed fairly good, though there were times when she accentuated the wrong syllables as she read aloud and defined the hundred names of Kali. To her righthand side, she had a large binder with all of the materials for the pūjā, which she read from throughout the hour-long ceremony. She was accompanied by three other younger women, whom she called “priestesses.” One of these women seemed to be functioning as her assistant, and she seemed more confident than the others because of her Sanskrit and bodily composure. She was also traditionally dressed, wearing a gold brocade sawar-kamiz. She had a long blonde braid that fell to her waist and wore red bangles and ankle bracelets (payals). She seemed to be dressed as a proper, married Indian woman. The other two women appeared to be novices, and Sundari Lakshmi guided them on how to hold their pūjā articles and their hands, what to do with ritual objects, and so on. There was also a man affiliated with the pūjā. He was young, white, and somewhat short, with thickly calloused feet and disheveled hair.

The pūjā was instructive and geared toward novices. Sanskrit was used but then explained in English. At the start, only thirty people or so were there to participate, but by the end it was more like sixty or seventy. The pūjā was somewhat traditional, with mantras to Kali, the recitation of her hundred names, and offerings of fire, sandalwood, flowers, clarified butter (ghi), and water. Sundari Lakshmi ritually bathed both the self and the goddess in metaphor as she poured offerings into the sacrificial fire. The structure of the fire sacrifice embodied Tantra-reminiscent elements in that practitioners ritually transformed themselves into Kali. After the pouring of oblations into the fire and the ritual transformation of practitioners’ bodies into Kali, we were told to choose partners. With our partners, we were instructed in a ritual blessing of the other’s body as a living embodiment of Kali. The partnering ritual was intimate, as is frequently expected at Shakti Fest, where participants are actively engaged in therapeutic spiritual work. My partner was a slender, young white woman who wore loose-fitting harem pants, a white T-shirt, and no rings or jewelry. She resonated with a calm and peaceful energy. We were instructed to invoke Kali mantras, and we dutifully repeated the Sanskrit and then followed the instruction to bless each part of the other’s body with our hands. Our bodies were knee to knee as we sat cross-legged in lotus posture. First, we were instructed to bless the head, then the throat, heart, eyes, ears, nose, lips, teeth, neck, the nape of neck, back, arms, shoulders, sides, and the “progenitor area.” This was the term Sundari Lakshmi used instead of calling the genitals by name. Neither of us touched the other’s genitals, but I did glance next to us at a male-female older couple who seemed to share an intimate relationship, and I saw him place his fingertips squarely on either side of her vulva. There was some giggling in the crowd, especially when we were asked to touch each other’s teeth. At one point, Sundari Lakshmi exhorted, “Get intimate! You need it. Sometimes we do this pūjā sitting in each other’s laps!” At this, everyone laughed. Afterward, we were instructed to “close out” our experience with each other and return our attention to the fire while Sundari Lakshmi concluded the pūjā with a communal meditation and closing mantras.

This ritual was performed and practiced at Shakti Fest by white ritual officiants who embodied the ethos of Hindu traditions while drawing on Vedic and Tantric sources. White yogis and spiritual seekers comprised the majority of participants who followed Sundari Lakshmi’s instructions to perform the ritual dedicated to the Hindu goddess Kali. Lakshmi claims to be an initiated yogini, pūjāri (priest), lineage holder, and authorized teacher who has lived and practiced her sādhana (spiritual practice) with adepts in Nepal, India, and Tibet. Her practice focuses on the embodiment of the divine feminine in Shakta Tantric lineages; she is serious about her study and her religious practice. According to her website, she is highly educated and has complemented her academic study with decades of practitioner-generated knowledge and numerous traditional Tantric “empowerments and transmissions.” Her biography claims that she is an “authorized teacher” based in this knowledge, and she can be found in yoga studios, festivals, and widely on the Internet offering teachings, rituals, pūjās, retreats, and online courses.

The example of Sundari Lakshmi introduces a commonplace pattern of embodied white possessivism, and the focus of this chapter will be to unfurl its complexities. In this representational politics, whites not only explore, learn about, and share in cultural and religious forms of racialized others, but also go one step further to embody, possess, extract, and redistribute that alterity as a form of social capital. Their access to alterity, deemed exotic, marks them with distinction in white society. It also identifies them as members of a “tribe”—a tribe defined by an affinity for religious exoticism, comprised of spiritual seekers who have also chosen to identify with radical others as a form of critique of their own culture, society, and ancestral heritage. In Deepak Sarma’s words, they imagine that they “can transform from the oppressor to the oppressed, from the colonizer to the colonized. Surely such an imagined transformation is only available to those who are privileged in the first place.”2 Sarma frames the white convert as engaged in either “mimicry or mockery” of Hindu traditions, but this dichotomy belies the ways in which initial acts of mimesis can develop into sincerely held identities. Particularly in the religious field, religious exoticism can be an initial step in a gradual process of self-transformation emerging from engagement with radically different cultures, customs, philosophies, and lifeways. The trouble lies not in the exploration and learning but in the representation, in the white possessivist logics that further economic exploitation and cultural erasure of people of color.

Many scholars have written similar critiques about the politics and ethics of cultural borrowing and appropriation.3 The Dakota scholar Philip Deloria writes about the history of whites “playing Indian,” performing the other in an attempt to cultivate their authentic selves.4 Laura Donaldson denounces “white shame-ans,” whites who appropriate, represent, and exploit Native religion as a form of fetish.5 Deborah Root writes of “cannibal culture,” linking together the commodification of difference and white consumption.6 But few have analyzed cultural appropriation through the study of religion, which raises particularly perplexing questions about the spectrum between spiritual tourism, cultural appropriation, and conversion.

In what follows, I employ some of the lessons learned from Indigenous studies to think through the appropriative practices of religious exoticism in transformational festivals. In these spaces, many whites adopt and perform aspects of “exotic” cultures and religions as instruments to further their spiritual growth and exploration. In so doing, some even cultivate new selves, as in the example of Sundari Lakshmi. These practitioners participate in religious exoticism as a means to cultivate self-distinction.7 As Graham St. John has argued, “The essential alterity signified by Amerindians, and the Natives of other regions, speaks of the primitivism that has tactically assisted, and continues to assist, Western desires for completeness and ideologies of progress. It also speaks of the practice of cultural appropriation through which a fantasized and projected otherness is adopted and purposed in the cause of establishing countermodernities, practices that have indeed generated a range of critiques from those exposing dubious claims to authority and indigeneity, ‘fakelore,’ ‘imperialist nostalgia,’ a ‘salvage paradigm,’ ‘postmodern neocolonialism,’ and entrepreneurial expropriation and commodification.”8 Religious exoticism is not necessarily problematic in its “desire for completeness” or cultural exploration; rather, the issue lies in its “dubious claims to authority and indigeneity.”

For example, in the yogic field, white yogic practitioners may align and identify with Indic cultures and traditions as a critique of Western modernity, but as they do, they also flood the yoga market and, more broadly, the New Age market. White yogis not only learn and practice yoga but also become representatives, entrepreneurs, and spokespeople because of their greater access to social capital. As a result, Indian yogis, and Indigenous and Asian spiritual leaders more broadly, are overwhelmed in the cacophony of dominant white voices, or silenced entirely. What began as an act of imagined solidarity becomes yet another tool for their oppression. Debates, often nonproductive ones, ensue regarding cultural appropriation, intellectual and cultural property, intellectual commons, conversion and its impossibility, and so on.

White Utopias focuses explicitly on these dynamics through the practice of yoga in transformational festivals. But here, in this first chapter, I broaden the lens to analyze religious exoticism more generally, and its impact in defining the intellectual fields of those who identify as spiritual but not religious. I argue that religious exoticism entails the turn toward alterity primarily as a critique of one’s own positionality—a search for something else, something beyond the familiar. Alterity—that is to say, racialized others and their cultural forms—becomes a tool instrumentalized to further self-critique and self-transformation. Religious exoticism engages with a variety of forms of alterity, the sole requirements of which are that they are disidentified with the self and the home culture. For this reason, Indigenous and Indic cultural forms become indexed with alterity, set outside and in contradistinction to Western modernity. Equated as such under the logics of white possessivism, they are easily hybridized and interchanged in the practices of religious exoticism.

THE SPIRITUAL BRICOLAGE OF TRANSFORMATIONAL FESTIVALS

Opportunities for spiritual growth vary widely between different transformational festivals. Each of the festivals discussed herein incorporates yoga into a variety of religious traditions, particularly Hinduism, Buddhism, Tantra, and Indigenous religions. Transformational festivals seamlessly transition between these traditions. In some cases, they are segmented into autonomous workshops and classes on subjects such as Buddhist meditation, Tibetan singing bowls, creating your own maṇḍala, Ayahuasca, and Native American ceremony. In other cases, however, instructors blend these traditions together within a singular workshop or class, for example when a yoga teacher splices Buddhist, Tantric, and Native American ideas into one yoga class. Echoing this, some vendors sell products focused particularly on the wares of one tradition (e.g., a shop selling Hindu murtis [religious figurines]), while others offer products that amalgamate a variety of Indigenous and Indic religious traditions (e.g., Hindu, Buddhist, Indigenous, and consciousness wares). From an aerial view, transformational festivals are broadly eclectic, exhibiting a variety of practices, worldviews, and products drawn from Indigenous and Indic religious traditions. The aesthetic of festival fashion also embraces Indigenous and Indic motifs blended with expressions of the mystical and magical—from body jewelry to “tribal” body paint, feathered headpieces, bindis, and gopi9 skirts.

With a few exceptions related to their more ritualistic and mystical forms, Abrahamic religions (Christianity, Judaism, and, in particular, Islam) are notably absent. Also absent are ap...