- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

For over a hundred years, the story of assimilation has animated the nation-building project of the United States. And still today, the dream or demand of a cultural "melting pot" circulates through academia, policy institutions, and mainstream media outlets. Noting society’s many exclusions and erasures, scholars in the second half of the twentieth century persuasively argued that only some social groups assimilate. Others, they pointed out, are subject to racialization.

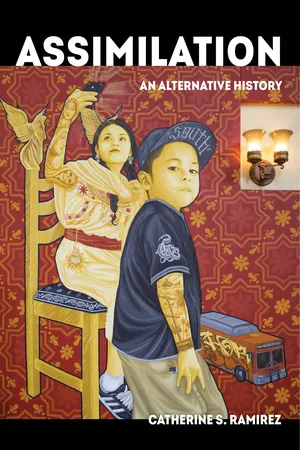

In this bold, discipline-traversing cultural history, Catherine Ramírez develops an entirely different account of assimilation. Weaving together the legacies of US settler colonialism, slavery, and border control, Ramírez challenges the assumption that racialization and assimilation are separate and incompatible processes. In fascinating chapters with subjects that range from nineteenth century boarding schools to the contemporary artwork of undocumented immigrants, this book decouples immigration and assimilation and probes the gap between assimilation and citizenship. It shows that assimilation is not just a process of absorption and becoming more alike. Rather, assimilation is a process of racialization and subordination and of power and inequality.

In this bold, discipline-traversing cultural history, Catherine Ramírez develops an entirely different account of assimilation. Weaving together the legacies of US settler colonialism, slavery, and border control, Ramírez challenges the assumption that racialization and assimilation are separate and incompatible processes. In fascinating chapters with subjects that range from nineteenth century boarding schools to the contemporary artwork of undocumented immigrants, this book decouples immigration and assimilation and probes the gap between assimilation and citizenship. It shows that assimilation is not just a process of absorption and becoming more alike. Rather, assimilation is a process of racialization and subordination and of power and inequality.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Assimilation by Catherine S. Ramírez in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Emigration & Immigration. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

The Paradox of Assimilation

There is a limit to our powers of assimilation, and when it is exceeded, the country suffers from something like indigestion.

—New York Times, May 15, 18801

My culture is a very dominant culture, and it’s imposing and causing problems. If you don’t do something about it, you’re going to have taco trucks on every corner.

—Marco Gutierrez, founder of Latinos for Trump, September 1, 20162

ASSIMILATION’S PREHISTORY

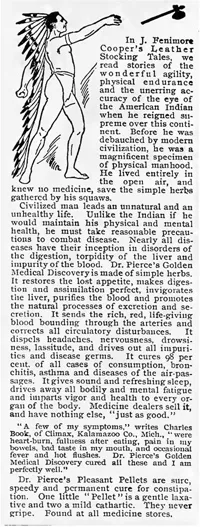

Dr. Pierce’s Golden Medical Discovery and Pleasant Pellets were patent medicines manufactured in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries at the World’s Dispensary Medical Association in Buffalo, New York. Made with queen’s root, bloodroot, mandrake root, and other ostensibly mystical ingredients, they were advertised as elixirs of “simple herbs” that could improve “nutritional assimilation,” thereby remedying loss of appetite, fatigue, nervousness, and other maladies.3 In a newspaper advertisement for these products from 1898, a Native American man wearing a loincloth and a long, feathered headdress is depicted hurling a tomahawk into the air (see figure 1). “Before he was debauched by modern civilization,” the ad proclaims, “the American Indian . . . was a magnificent specimen of physical manhood. He lived entirely in the open air, and knew no medicine, save the simple herbs gathered by his squaws.”4 A “real” Indian, Dr. Pierce’s American Indian is unspoiled and unassimilated.5

Figure 1. Advertisement for Dr. Pierce’s Golden Medical Discovery and Pleasant Pellets. The Rural New-Yorker, November 5, 1898. Used with permission from American Agriculturalist. Copyright Informa.

The ad for Dr. Pierce’s Golden Medical Discovery and Pleasant Pellets sheds light on assimilation’s multiple meanings. It also presages the ongoing contest over this term’s significance. In addition to referring to a process of becoming more alike, assimilation, in its most general sense, refers to a process of absorbing. For example, as early as the seventeenth century it could mean digestion, the “absorption of nutriment into the system.”6 However, over time assimilation took on new, politically charged meaning in the United States as social groups moved through space and came into contact with one another—for instance, as the nation-cum-empire stretched across and beyond the North American continent; as the US government and its agents broke up tribal lands and removed Native Americans from their homes and communities; as African Americans relocated from the rural South to the urban North; and as immigrants from all parts of the globe arrived at the nation’s ports of entry.

By the start of the twentieth century, assimilation referred not only to a biological or physiological process but also to a social and cultural one. In 1894 economist Richmond Mayo-Smith defined assimilation as the “mixture of nationalities” that resulted from immigration to the United States.7 Signaling that the concept had indeed moved beyond the natural and biological sciences, sociologist Sarah E. Simons observed in 1901 that “[w]riters on historical and social science” were “just beginning to turn their attention to the large subject of assimilation.”8 “[I]n the future treatises on assimilation will form vast libraries,” she predicted.9 Thirteen years later, Robert Ezra Park, considered by many scholars to be “one of the giants of early American sociology,” connected assimilation’s old and new meanings.10 “By a process of nutrition, somewhat similar to the physiological one,” he wrote, “we may conceive alien peoples to be incorporated with, and made part of the community or state.”11

As these early social scientific definitions underscore, assimilation has been associated with immigration in the United States since the late nineteenth century. Yet the ad for Dr. Pierce’s products offers a glimpse of what I call assimilation’s prehistory, of some of the term’s meanings before it was connected to immigrants and immigration. In addition to referring to a physiological and biological process, assimilation was used synonymously with “civilization” through the early twentieth century. As the opposite of savagery and barbarism, as an “achieved social order or way of life,” and as a “modern social process” whose “effects [are] reckoned as good, bad or mixed,” civilization is a conceptual precursor of assimilation as social and cultural process.12

Along with African Americans, Native Americans once played a salient role in conversations about assimilation. Examining the connection between civilization and assimilation brings that role into relief. In the Civilization Fund Act of 1819, the US Congress charged “capable persons of good moral character” with imparting “the habits and arts of civilization” to Native Americans.13 Sixty years later, on the cusp of what is known in federal Indian history as the allotment and assimilation era (1887–1943), Richard Henry Pratt set out to civilize and, as he put it, to “citizenize” indigenous youth when he founded the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, the first federally funded, coeducational, off-reservation boarding school in the United States.14 As I discuss in chapter 2, Carlisle was one in a long line of colonial educational institutions that sought to “civilize” nonwhite peoples in and beyond the continental United States by subordinating them. Pratt modeled Carlisle after the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute, a school for African Americans and one of the first historically black colleges and universities. He upheld the deracination of African slaves and their US-born descendants as a model for civilizing Native Americans. In other words, he believed that Native Americans could be assimilated if they, too, were plucked from their homes and forced to live with white Americans. He described the process of civilizing so-called backward races as “assimilation under duress.”15

While “backward” races were seen as in need of civilizing, they were formally excluded from the polity. That is, they could be civilized, but they could not be citizens, at least not until 1868, when the Fourteenth Amendment granted US citizenship to “[a]ll persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof.”16 The first statute to codify naturalization law in the United States, the Naturalization Act of 1790, restricted US citizenship to free white persons. The Fourteenth Amendment transformed African Americans into US citizens, at least in name, but it did not apply to Native Americans. In 1924 the Indian Citizenship Act (also known as the Snyder Act) extended US citizenship to them.

Yet before the Snyder Act was passed, Native Americans had to prove that they were worthy of US citizenship. For instance, the Dawes Act of 1887 and the Burke Act of 1906 held out the promise of US citizenship to Native Americans, but only after a probationary period of twenty-five years. During that probation, Native Americans who aspired to be US citizens had to live “separate and apart from any tribe of Indians.”17 What is more, they had to demonstrate that they had “adopted the habits of civilized life” and were “competent and capable of managing [their] affairs.”18 In short, assimilation was a transactional trial. As Pratt’s motto, “Kill the Indian . . . and save the man,” stressed, the price for civilization and citizenship was the Indian’s very Indianness.19

ASSIMILATION THEORY: ETHNICITY AND RACE

As the meanings of civilization and assimilation diverged over the course of the twentieth century, assimilation came to be associated more with people recognized as immigrants and less with Native Americans and African Americans. Assimilation and immigration were conjoined via such concepts as Americanization, the metamorphosis from non-American to American; Anglo-conformity, the dissolution of the immigrant or minority group’s culture by an Anglo-Protestant mainstream; acculturation, adaptation to a different culture, often the dominant one; incorporation, the union of two or more things into one body (and sometimes, a synonym for naturalization); and integration, the inclusion of different cultures or groups in society, often or presumably as equals (and the opposite of segregation). Like civilization, some of these terms—in particular, Americanization and Anglo-conformity—connote the imposition and presumed superiority of one way of life, the American and Anglo-American, over another.

Theories and models of assimilation say just as much about how society and the nation are perceived—however idealized—as they do about the putative processes by which people are absorbed into or adapt to that society and nation. For example, assimilation as Anglo-conformity assumes that the majority of Americans are “chiefly of Anglo-Saxon extraction,” “Caucasian racial stock,” and “the Protestant faith.” Assimilation into the white Anglo-Protestant “dominant culture group” is unidirectional.20 This framework tends to be associated with “[e]arly assimilation scholars.”21 It is widely perceived to have been abandoned “[w]hen the notion of an Anglo-American core collapsed amid the turmoil of the 1960s” and to have been eclipsed by multiculturalism, a late twentieth-century offshoot of cultural pluralism.22 However, political scientist Samuel P. Huntington resurrected Anglo-conformity in 2004 when he warned that immigration from Latin America threatened to destroy the “core Anglo-Protestant culture” of the United States.23

Unlike Anglo-conformity, cultural pluralism valorizes cultural diversity, albeit of a limited sort. When philosopher Horace M. Kallen conceived of cultural pluralism in the early twentieth century, he sought to show the compatibility of “continental” (southern, central, and eastern European) immigrants with American democracy.24 As a child, he emigrated with his family in 1887 from what is now Poland as part of the Great Wave: the arrival of some twenty million immigrants to the United States between 1880 and 1924.25 During this period, immigrants hailing from southern, central, and eastern Europe were called “new” immigrants. As I discuss in chapter 3, some self-proclaimed “old stock” (Protestant, of northwestern European descent) Americans looked down on the “new” immigrants, doubted their ability to assimilate, and effectively blocked any more from immigrating via restrictive legislation, such as the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1924 (also known as the Johnson-Reed Act). Against a backdrop of growing xenophobia and anti-Semitism, cultural pluralism challenged biological racism and “the grey conformism of the melting-pot.”26 All the while, it upheld “American civilization” as “the perfection of the cooperative harmonies of ‘European civilization.’”27

Its Eurocentrism notwithstanding, cultural pluralism posits that the United States is a “diverse and dynamic” host society and receiving country.28 The United States not only shapes immigrants; it is also shaped by them. Cultural pluralism informs assimilation theory in sociology, the academic discipline that has contributed the most to theorizations of assimilation, in at least two ways. First, cultural pluralism helped lay the groundwork for the ethnicity paradigm, “the mainstream of the modern sociology of race,” according to sociologists Michael Omi and Howard Winant.29 Second, cultural pluralism is the foundation of “the pluralist perspective” on ethnicity.30

In theorizing assimilation, scholars have distinguished ethnicity from race. There are many definitions of ethnicity; among them are a basic group identity; real or fictive common ancestry; a means of mobilizing a certain population as an interest group; “a process of construction or invention which incorporates, adapts, and amplifies preexisting communal solidarities, cultural attributes, and historical memories”; and “a social boundary . . . embedded in a variety of social and cultural differences between groups.”31 Since the second half of the twentieth century, definitions of ethnicity have emphasized the social and cultural.

Race, meanwhile, is understood as “a concept that signifies and symbolizes social conflicts and interests referring to different types of bodies.”32 Put another way, race is a construct that merges the social and somatic. That said, things that do not necessarily have a clear or direct link to the physical or visual—for example, names, words, languages, and accents—may nonetheless come to be associated with race. The process whereby racial categories are produced and understood as part of a social hierarchy is known as racialization.

Where the assimilationist perspective maintains that ethnic differences dissolve in the melting pot that is the United States, the plura...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- 1. The Paradox of Assimilation

- 2. Indians and Negroes in Spite of Themselves: Puerto Rican Students at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School

- 3. Demography Is Destiny: Negroes, New Immigrants, and the Threat of Permanence

- 4. The Moral Economy of Deservingness, from the Model Minority to the Dreamer

- 5. Impossible Subjects: Dissident Dreamers, Undocuqueers, and Oaxacalifornixs

- Epilogue: Notes from the Interregnum

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index