![]()

1. The archaeology of post-depositional interactions with the dead: an introduction

Edeltraud Aspöck, Alison Klevnäs and Nils Müller-Scheeßel

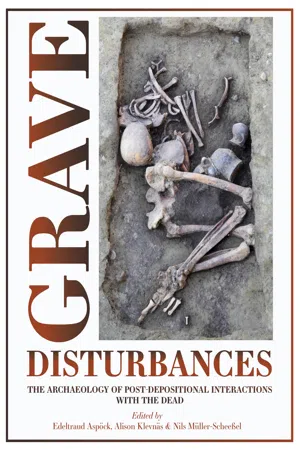

During excavations we often encounter mortuary deposits which show evidence of disturbance. Graves, especially inhumation burials as opposed to cremations, readily show signs of disorder. Human bones may be displaced and intermingled with grave goods, or traces of pits or damage to coffins or other containers may show that others have been digging before the archaeologists arrived. This book explores past human interactions with mortuary deposits, delving into the different ways graves and human remains were approached by people in the past and the reasons that led to such encounters. The primary focus of the volume is on cases of unexpected interference with individual graves soon after burial, that is, re-encounters with human remains which do not seem to have been anticipated by those who performed the funerary rituals and constructed the tombs. But in addition, reuse of graves at later stages also features in some of the case studies, as well as practices concerning double or collective graves in which reopening and manipulation of previous deposits is required when the “new” dead are added. Multiple types of post-depositional practices may frequently be seen in the same period and region and sometimes at the same burial site or even in a single grave.

The observation that graves were often deliberately disturbed in the past is long-standing, but the phenomenon has not been a popular subject for research, until recently remaining on the margins of archaeological discourse. Undisturbed mortuary deposits show how bodies were deposited, which grave goods and furniture were there originally and – subject to natural taphonomic alterations – frequently offer collections of valuable artefacts for study and display. As “closed contexts”, undisturbed graves have long been valued as important methodological tools for establishing typologies and chronologies. For social analysis of cemeteries, complete sets of grave goods and skeletal evidence that is as exhaustive as possible are basic requirements. In “disturbed” graves we cannot say for certain the number or types of grave goods that were once deposited and, if an interment has been heavily interfered with, we may not know how the body was placed, and in some cases not even how many individuals were initially present. Accordingly, for most of their history, disturbed graves were generally deemed interesting and worth analysis only according to the degree that they still showed evidence of the original deposition. However, paradigms in mortuary archaeology have changed: recent research has moved away from researching the normative and the typical, and with this move interest in post-depositional practices has been rising (e.g. Aspöck 2008; Murphy 2008).

One consequence of the perception of all deliberate re-entries into burials in the past as essentially damage to the archaeological record was limited interest in the reasons for post-depositional interferences in graves. The go-to explanation was that ancient “grave robbers” in search of valuables would be accountable for the traces of disturbance seen by modern excavators in most if not all cases (Fig. 1.1; Fig. 1.2). Indeed, as this book shows, this interpretation was invoked whether it was early medieval cemeteries in Europe or the tombs of the Maya that were found disturbed. Thus for a long time an understanding prevailed that in the past, graves were seen – at least by the robbers and their affiliates – principally as hoards of objects valuable and useful to the living for materialistic reasons. And since motives for “grave robbing” seemed plain and self-explanatory, the behaviour as such never aroused much interest in scholarly discourse. This paradigm remained a vigorous part of archaeological narratives for a long time, indeed perhaps still remains so. It has been influential in particular in periods with large-scale occurrence of grave reopening and object removal, notably the Early Bronze Age of central Europe and the early Middle Ages of western and central Europe, and was only occasionally challenged by those looking into the evidence more closely.

Fig. 1.1: Image from the 15th-century illuminated manuscript “The Decameron” illustrating the robbery of the grave of Archbishop Filippo Minutolo. The image represents the only known ancient illustration of an act of grave robbery. Paris, Bibl. de l’Arsenal, ms. 5070 réserve, f° 54v (Courtesy of Bibliothèque nationale de France).

In the last decade or so, in-depth research has begun into what is now preferably described under more neutral categories such as “post-burial interventions”, “grave reopening” or “post-depositional practices”. Both the new interest and new terminology are based on awareness that the reopening of a grave is in many cases by no means a criminal act, nor laden with the negative sentiment implied by the term “robbery”. For these reasons, we avoid the term “grave robbery” when presenting a range of recent approaches to the topic in this volume, even though it is sometimes intended as simply a technical term for past interference with mortuary deposits. We contend that “grave robbery”, used equally for the description of archaeological evidence and its interpretation, mixes different stages of the research process and is therefore misleading. It also depletes interpretative power in those contexts in which reopening does in fact appear to have been motivated by illicit acquisition, which themselves provide opportunities to interrogate ideas about the dead and their kin as property-holders. Instead, we prefer more neutrally descriptive terms such as “reopening”, “deliberate disturbance” or “manipulation”. These sometimes come across as awkward neologisms, especially when the individuals who reopened graves are denoted as “reopeners” or “manipulators”, but these alternative terms help to avoid preconceptions about the nature and motives of reopening across contexts. Use of such alternative terms has become more and more commonplace in studies critical of previous models of interpretation.

Fig. 1.2: “Grave-robbers” looting the landscape (Neugebauer 1991, fig. 34. Concept: J.-W. Neugebauer, Drawing: Leo Leitner 1983, Courtesy of Christine Neugebauer-Maresch).

The papers gathered here give new insights into the forms and motivations for past re-entries into graves in archaeological contexts across the world. They demonstrate that the reopening of burials in the past is an important source for past cultural practices, embedded in social notions of what is proper, what is necessary and what is possible. In the remainder of this introduction we will first introduce previous research and outline how the study of post-depositional practices emerged as a new subfield in funerary archaeology. Then comes discussion of methodological developments in the excavation, analysis and interpretation of reopened graves. Finally we give an overview of different types of practices for which graves were reopened, discussed in relation to the case studies in this volume. We will focus on recent developments – and the challenges that they entail – which make this area of research a fascinating and rewarding topic.

Post-depositional practices: emergence of a new subfield in mortuary archaeology

The fact that at least some graves in most archaeological periods are not closed contexts, but have been entered and disturbed in the intervening centuries was noticed early on in the development of the archaeological discipline. Mentions of graves “robbed in antiquity” are to be found in many publications from the 19th century onwards (e.g. for early medieval Europe Cochet 1854; Brent 1866; Nicaise 1882; Lindenschmit 1889). However, for the reasons set out above, there was little incentive to explore the subject more systematically, beyond a few celebrated cases in which written sources provide both explanatory frameworks and sensational detail, such as the New Kingdom of Egypt (e.g. Silverman 1997, 196; Aston, this volume) and the Scandinavian Late Iron Age (e.g. Brøgger 1945; Bill and Daly 2012; Klevnäs 2016). Hence until very recently only a handful of conferences and publications dealt specifically with the subject, with little shared discussion of general methodological and interpretative possibilities.

Such interest as was demonstrated in graves disturbed soon after burial arose largely within German-language scholarship, where it was stimulated by the high numbers of rifled interments discovered in the early medieval row-grave cemeteries characteristic of the former borderlands of the Roman Empire. The colloquium titled Zum Grabfrevel in vor- und frühgeschichtlicher Zeit (On the desecration of graves in pre- and proto-historic times) which took place in Göttingen, Germany in 1977, was one of the first major events dedicated to the topic of disturbed burials. The proceedings (Jankuhn et al. 1978; Pauli 1981; Lorenz 1982) were probably the first extensive publication examining post-depositional practices and remain a seminal reference for research concerned with the reopening of burials in pre- and protohistoric Europe. Grave-robbery in Germanic legal history was the starting point for the colloquium; in general the papers show the traditionally steering influence of textual and legal sources on archaeological approaches to reopening. Roman and early Germanic law codes include strong condemnation of interference with burials, which combined with modern cultural preconceptions, shaped an enduring perception of post-depositional practices as unlawful activities and promoted the idea that entering a grave must at all times be a form of sacrilege. As implied by the use of the term Grabfrevel in the title, disturbing the peace of the dead was characterised as an illicit activity, probably carried out by strangers, outcasts and criminals, perhaps during night-time or after the cemeteries had been abandoned, with the aim of plundering and taking as many precious goods out of graves as possible, without regard for the buried human remains.

The 1977 colloquium focused mainly on the early medieval period but also included contributions on grave disturbance in Bronze Age central and northern Europe (Raddatz 1978; Thrane 1978), Iron Age central Europe (Driehaus 1978), the Roman Empire and Merovingian kingdoms (Behrends 1978; Krüger 1978; Nehlsen 1978; Raddatz 1978; Roth 1978; Schmidt-Wiegand 1978), and Viking Age Scandinavia (Beck 1978; Capelle 1978; Düwel 1978). Helmut Roth’s article on Grabfrevel im Merowingerreich is still widely cited, as it represented by some distance the most in-depth investigation. This large-scale overview of regional and temporal patterns was based on a quantitative survey of reopening levels in a large number of early medieval cemeteries and remains a starting point for research into grave disturbance in the period.

Following the Göttingen colloquium, discussions of grave disturbance continued mainly in the form of subsections in cemetery publications. Graves excavated to high standards frequently revealed useful detail about reopening events, but the focus was largely on single sites (e.g. Simmer 1988; Kokowski 1991; Perkins 1991; Thiedmann and Schleifring 1992; Codreanu-Windauer 1997), with occasional explorations of evidence in particular regional contexts (e.g. Adler 1970; Rittershofer 1987; Brendalsmo and Røthe 1992; Randsborg 1998; Tamla 1998; Plum 2003). A notable exception was the lively discussion around central European Early Bronze Age reopening in the 1980s and 90s. Excavations of a number of Early Bronze Age cemeteries in eastern Austria were carried out by Johannes-Wolfgang Neugebauer and Christine Neugebauer-Maresch (Neugebauer 1991; Neugebauer-Maresch and Neugebauer 1997; Savage 1997, 253; Sprenger 1999) with a deliberate focus on questions about the prolific reopening and object removal frequently seen in this period (compare Müller-Scheeßel et al., this volume). Neugebauer identified elements of violence and lack of respect for the human remains and, as a result, reproduced the prevailing picture of grave robbery as an illicit activity that was carried out by “armed bands” (Neugebauer 1991, 127–128; 1994; Fig. 1.2). Similarly François Bertemes (1989, 130) examined disturbed graves in the area of the middle Danube, claiming that in each community there would be unwritten laws, for example stipulating that the grave and the remains of the dead should not be touched. An alternative explanation was offered by Bernhard Hänsel and Nándor Kalicz (1986, 52) who argued that in this period valuable grave goods were recovered and returned to the families and heirs after the period of fleshy decomposition, during which the corpse skeletonised – the idea of a “decent interval” after which it may be acceptable to interfere with burials is frequently put forward (Klevnäs 2013, 49–51). Meanwhile growing awareness of the reopening phenomenon, at least in the periods in which it is most common, led to its more frequent mention in general discussions of burial custom (e.g. Steuer 1982; Bartelheim and Heyd 2001; Effros 2002; 2003).

Since 2000 a new wave of studies has appeared in the form of research dissertations, showing a new dynamic in this field of research (e.g. Aspöck 2002 [2005]; Kümmel 2007 [2009]; van Haperen 2007 [2010]; Klevnäs 2010 [2013]; Zintl 2012 [2019]; Noterman 2016; van Haperen 2017). These are characterised by stronger theoretical awareness and a critical attitude towards the catch-all “grave-robbery” explanation. More neutrally descriptive terminology is used, and alternative explanations are systematically considered (Aspöck 2005; Kümmel 2009; van Haperen 2010; Klevnäs 2013). Meanwhile the French-language...