![]()

1

The Early 5th-Century BCE Fort of Larisa East (Aeolis) as Part of a Multi-Centred Defence System

Ilgın Külekçi and Turgut Saner

Larisa is located near modern Buruncuk, 40 km north of Izmir (ancient Smyrna), close to the Aegean coast of Asia Minor.1 It overlooks the fertile Hermos (Gediz) Plain along the eponymous river, which bridges the ancient region of Aeolis with inland Lydia. Its occupation goes back to the Neolithic period, and the Bronze Age is also represented by some wall fragments and small finds. However, most of the visible remains found on site at Larisa date between the 6th and 4th centuries BCE. That means that a considerable part of this city’s lifetime was under Persian rule in Anatolia. Larisa was a prosperous stronghold due to its advantageous location, and it mostly remained loyal to the Great King of Persia. The city consists of two core settlements on the two hills of the Buruncuk ridge – ‘Larisa East’ and ‘Larisa West’ – and their surrounding area (Fig. 1.1).

The architectural remains reveal that Larisa West was the residence area of the ruling class. Its southern slopes surrounded by city walls define the main city area where the urban elite lived, whereas the steep northern slope was also reserved as a city area furnished with a theatre and fortification walls. An extensive necropolis with miniature tumuli and outer fortifications in the north-east complete this representative compound. The rulers manifested their power with the construction of monumental edifices such as fortification walls, temples, buildings for convivial meetings and larger tumuli in the necropolis. The urban elite followed the same path, living in the city area partially arranged in a regular system, having tumulus graves with elaborate masonry, and most probably contributed to the stately meetings in the rulers’ area. On the top of the higher hill on the east, a fort and a smaller settlement area represent a military spot with the dwellings for what appear to be soldiers and farmers.

The history of the fieldwork in Larisa goes back to the beginning of the 20th century. The first excavation in 1902 by Lennart Kjellberg (Uppsala) and Johannes Boehlau (Kassel) was followed by three further campaigns in 1932, 1933 and 1934. The results were published in three ‘Larisa am Hermos’ volumes on architecture, architectural terracottas and small finds.2 Fieldwork was limited to the excavation of the acropolis, with minor soundings in the necropolis, at the 4th-century city walls, and trial trenches in the city area. The survey of the eastern hill only covered the documentation of the fort with a brief plan and section,3 whereas the settlement area remained unexplored. From 2010 onwards an architectural survey, under the supervision of Prof. Turgut Saner (ITU), focuses on the settlement and architectural remains in many different aspects ranging from topographical matters to building elements and construction details.4 By investigating the two settlement cores within their immediate peripheries, an overall layout of Larisa begins to emerge.

Considering the topographical and chronological aspects, Larisa’s defence infrastructure draws a multi-levelled picture. According to the archaeological evidence, the acropolis circuit in Larisa West was built at the beginning of the 5th century BCE. The urban fortifications were also constructed in the same period, as is identified by the poor remains of the same Lesbian masonry. The entire undertaking can be considered within the frame of the loyal attitude of Larisa towards the Persians during the course of the Ionian Revolt that took place against the Persian rule in the early 490s. After the de-fortification of the city by the Athenians towards the end of the 5th century BCE, the walls were rebuilt in the 4th century BCE following more or less the same course. Within this undertaking, the acropolis grounds were enlarged and strengthened with bulwarks, whereas a northern defence and a diateichisma, which defines an outer ward, were added. The entire western defence works were also solidified – probably in the 4th century BCE – by the construction of an outer wall (Boehlau and Schefold 1940, 51).

Fig. 1.1: Larisa (Buruncuk), greater settlement layout.

The Fort

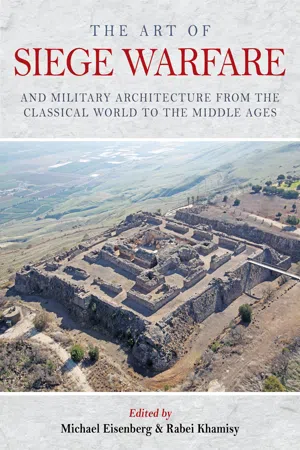

The fort in Larisa East, which is the actual focus of this contribution, completes the organization of the defence system of Classical Larisa. The eastern fort crowns the topmost part of a 180 m-high rocky hill about 1.5 km distant from Larisa West, i.e. the main city (Fig. 1.2). The fort overlooks a small settlement, which takes up the natural terraces below (Fig. 1.3).

Following the topographical configuration, the fort was given a triangular shape. Its surrounding curtain walls are about 1.7–1.8 m thick. The eastern and southern walls are approximately 80 m long, whereas the northern flank measures about 100 m. The structure does not feature towers. Nevertheless, the north-eastern and south-eastern edges are designed with recesses and corners, so as to form tower-like projections. Two cross-walls divide the triangular interior area into three parts, the lower and biggest area revealing a large, circular cistern and other building remains. Close to the north wall, there is a small structure built with Lesbian masonry. The long cross-wall with its roughly hewn blocks attached to this small building is obviously a later addition. Three gates can be identified; one in the east, one in the north and one in the south.

In order to date the fort in Larisa East accurately, three basic criteria can be analysed. These factors increase the likelihood of an initial construction as contemporary with the early 5th-century BCE acropolis circuit of the western settlement. First, the Lesbian masonry of both edifices reveals fine workmanship, with traces of drafted edges on the block surfaces and deep hollows caused by masons’ blows with a pick. The pick marks cover the surface of the blocks homogenously, however, the depth of single holes is different; some remain close to the surface, yet some reach even deeper than the intended smooth surface of the block. As for the second criterion, the constructional features of both walls, namely those of eastern and western forts, are also exactly the same. According to this practice, first, a solid rock-bed was chosen to provide foundation, and it was additionally supported with foundation blocks. Upon it comes a toichobat (the stone layer of a building following the foundations where the visible parts of the walls rest – ὁ τοιχοβάτης), which is slightly recessed. The surface of toichobat blocks are sometimes finely worked and sometimes only roughly hewn. The toichobat layer carried the rising wall, which was again placed some centimetres receded (Fig. 1.4). The above-mentioned Lesbian masonry with deep pick marks refers to the rising wall base. The rest of the wall base was most probably constructed using mud-bricks, as stated in the 20th-century excavation reports of Larisa. And finally the stone extraction methods are also common considering the eastern fort and the acropolis walls of the western settlement. According to the observations on site, blocks were split from natural rocks by opening a series of wedge-holes. Their numerous remains can still be seen on rock surfaces and on the extracted blocks used in the masonry of the eastern and western forts. These constructional and technical aspects together confirm the suggestion that the fort in Larisa East was constructed at the beginning of the 5th century BCE, as part of the same construction initiative as the western acropolis.

Fig. 1.2: Larisa East seen from south-east.

Fig. 1.3: Plan and section of Larisa East.

This comparison allows us to perceive the sophisticated defence architecture in Larisa at the beginning of the 5th century BCE as a centrally organized undertaking. It can be attributed to the same authority who ruled in Larisa and consolidated its existence with representational attitudes as mentioned above. The eastern fort appears to have provided the western settlement with a shelter in case of threat; it was obviously in use also during the course of the 4th century BCE. The principal evidence is the addition of rectangular masonry at certain sectors close to the peak of the hill. The enlargement of the rulers’ residence in the west by means of new wall sectors with rectangular masonry also points towards the central authority in Larisa that claimed control in the 4th century BCE.

Fig. 1.4: Larisa East, eastern wall of the fort showing bed-rock, recessed toichobat, and the uppermost layer of wall base.

The multi-foci constellation of Larisa’s early 5th century BCE defence must have developed due to the special topographical conditions of the mountain ridge of Larisa. The furthest south-western edge of the ridge was seemingly preferred as a place of residence because of its remarkable setting for rulers’ self-manifestation and cult places, and the elite citizens’ dwelling. However, its location could only partially serve for defence purposes.

The same can be said about the acropolis. Its defence had to be designed more solidly than that of the eastern fort, because the altitude of the so-called acropolis in the west, with its palaces, is lower, and its plateau-like topography was more vulnerable. This explains why the circuit wall in the west is much stronger compared to the eastern fort. The thickness of the curtain walls is about 2.5–2.6 m and the structure is furnished with eight towers. The fort in Larisa East, on the other hand, is integrated with the edges of steep rock faces. These were occasionally bonded together to provide a base for the actual walls atop them. Thus, Karl Schefold’s explanation in the 20th-century Larisa research publication that ‘the fort in the east must have functioned as the natural acropolis of Larisa’ finds its reflection in this monocratically organized constellation of the forts (Boehlau and Schefold 1940, 116).

The Settlement Area

Below the eastern wall of the fort, the south-eastern extension of the hill designates the eastern settlement area. Extending down through the plain, big masses of rocks and sudden topographical changes limit further expansion for dwelling. The architectural remains cover an area of roughly 1.7 ha (Figs 1.3 and 1.5) with a width of 75 m and a length of 250 m. Following the descending natural topography of the terraces, the settlement area with dwellings was founded on four parallel sections (Terrace 0–3), thus revealing a multi-partite organization.

The first part (Terrace 0) immediately below the fort is a rocky area including big masses of rocks supporting the eastern projections of the fort. Especially on the south and north of the terrace, large stone blocks are integrated with sharply declining rocks, and hence define the boundaries of the uppermost part of the settlement. The only closed space identified here is located on the centre of the terrace, a relatively plain area over the retaining walls, and covers an area of approximately 30 m2 with walls 60 cm thick. ...