- 166 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Timing for Animation, 40th Anniversary Edition

About this book

Timing for Animation has been one of the pillars of animation since it was first published in 1981. Now this 40th anniversary edition captures the focus of the original and enhances this new edition with fresh images, techniques, and advice from world-renowned animators. Not only does the text explore timing in traditional animation, but also timing in digital works.

Vibrant illustrations and clear directions line the pages to help depict the various methods and procedures to bring your animation to life. Examples include timing for digital production, digital storyboarding in 2D, digital storyboarding in 3D, and the use of After Effects, as well as interactive games, television, animals, and more. Learn how animated scenes should be arranged in relation to each other, how much space should be used, and how long each drawing should be shown for maximum dramatic effect.

All you need to breathe life into your animation is at your fingertips with Timing for Animation.

Key Features:

- Fully revised and updated with modern examples and techniques

- Explores the fundamentals of timing, physics, and animation

- Perfect for the animation novice and the expert

Get straight to the good stuff with simple, no-nonsense instruction on the key techniques like stretch and squash, animated cycles, overlapping, and anticipation.

Trying to time weight, mood, and power can make or break an animation—get it right the first time with these tried and tested techniques.

Authors

Harold Whitaker was a BAFTA-nominated professional animator and educator for 40 years; many of his students number among today's most outstanding animation artists.

John Halas, known as "The father of British animation" and formerly of Halas & Batchelor Animation Studio, produced more than 2,000 animation films, including the legendary Animal Farm (1954) and the award-winning Dilemma (1981). He was also the founder and president of the International Animated Film Association (ASIFA) and former Chairman of the British Federation of Film Societies.

Tom Sito is Professor of Animation at the University of Southern California and has written numerous books and articles on animation. Tom's screen credits include Shrek (2001) and the Disney classics Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988), The Little Mermaid (1989), Beauty and the Beast (1991), Aladdin (1992), and The Lion King (1994). In 1998, Tom was named by Animation Magazine as one of the 100 Most Important People in Animation.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Timing to Suggest Weight and Force—1

Timing to Suggest Weight and Force—2

Timing to Suggest Weight and Force—3

Timing to Suggest Weight and Force—4

Timing to Suggest Force: Repeat Action

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Foreword

- Preface to the 3rd edition

- Preface to the 1st edition

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Timing for Broadcast Media

- What Is Good Timing?

- The Storyboard

- Traditional Storyboards

- Digital Storyboarding

- Additional Storyboard Effects

- Responsibility of the Director

- Directing for Interactive Games

- The Basic Unit of Time in Animation

- Timing for Television, Web-Based Programming vs. Timing for Features

- Slugging

- Bar Sheets

- Timing for a Hand-Drawn Film: Exposure Charts or Exposure Sheets

- Timing for an Overseas Production

- Timing for a 2D Digital Production

- Timing for a 3D Digital Production

- Timing for an Actor-Based Program (Performance or Motion Capture)

- Animation and Properties of Matter

- Movement and Caricature

- Cause and Effect

- Newton’s Laws of Motion

- Objects Thrown Through the Air

- Timing of Inanimate Objects

- Rotating Objects

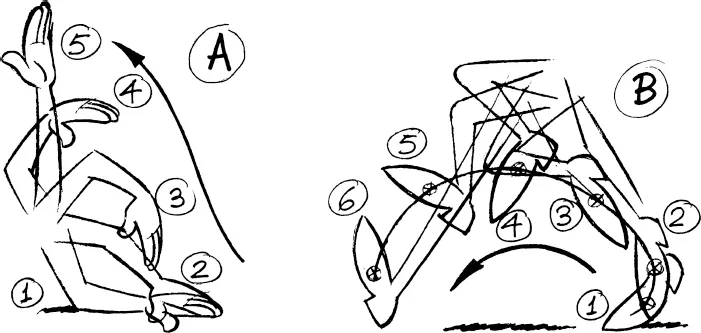

- Force Transmitted Through a Flexible Joint

- Force Transmitted Through Jointed Limbs

- Spacing of Drawings—General Remarks

- Spacing of Drawings

- Timing a Slow Action

- Timing a Fast Action

- Getting Into and Out of Holds

- Single Frames or Double Frames? Ones or Twos?

- How Long to Hold?

- Anticipation

- Follow Through

- Overlapping Action

- Timing an Oscillating Movement

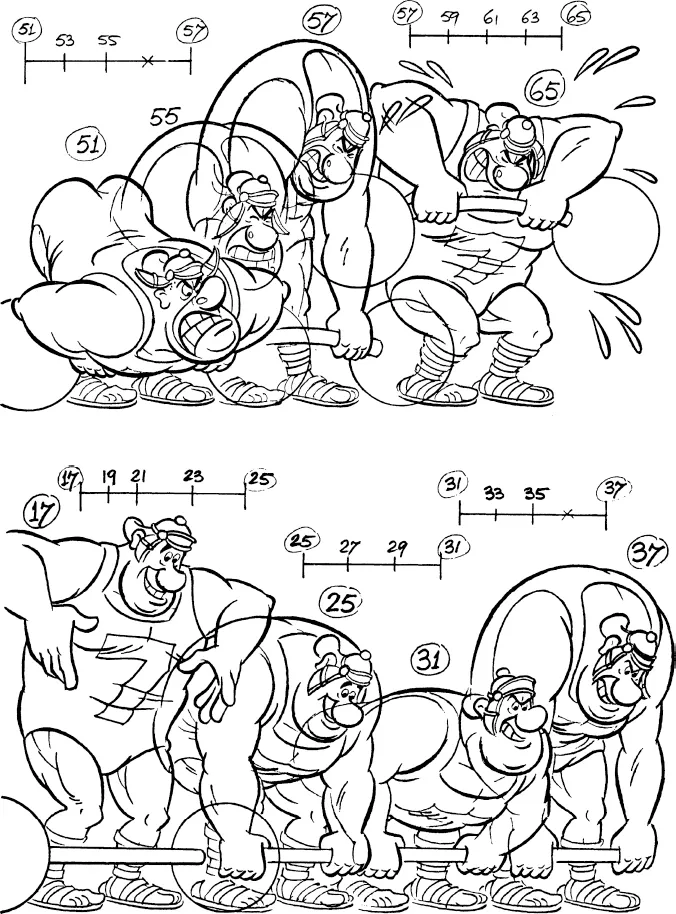

- Timing to Suggest Weight and Force—1

- Timing to Suggest Weight and Force—2

- Timing to Suggest Weight and Force—3

- Timing to Suggest Weight and Force—4

- Timing to Suggest Force: Repeat Action

- Character Reactions and “Takes”

- Timing to Give a Feeling of Size

- The Effects of Friction, Air Resistance, and Wind

- Timing Cycles—How Long a Repeat?

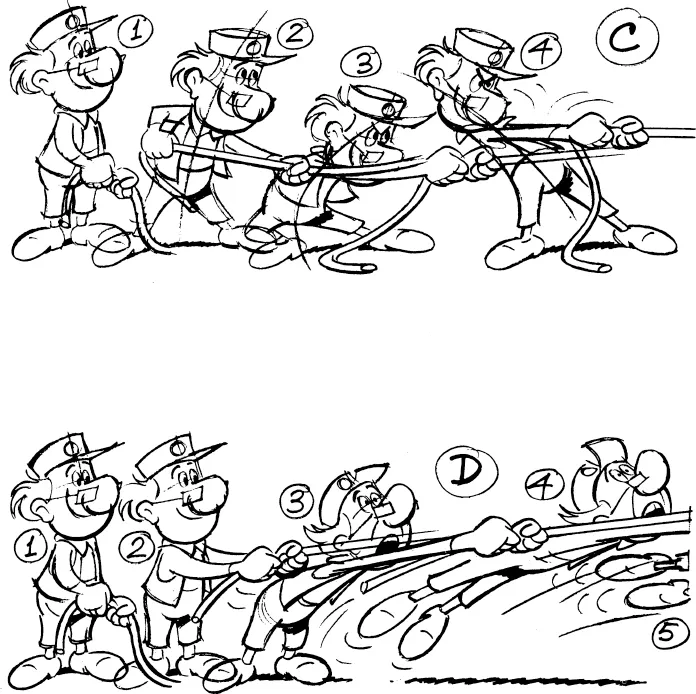

- Scenes with Multiple Characters

- Digital Crowds (Massive)

- Effects Animation: Flames and Smoke

- Water

- Rain

- Snow

- Explosions

- Repeat Movements of Inanimate Objects

- Timing a Walk

- Types of Walk

- Spacing of Drawings in Perspective Animation

- Timing Animals’ Movements: Horses

- Timing Animals’ Movements: Other Quadrupeds

- Timing an Animal’s Gallop

- Bird Flight

- Drybrush (Speed Lines) and Motion Blur

- Accentuating a Movement

- Strobing

- Fast Run Cycles

- Characterization (Acting)

- The Use of Timing to Suggest Mood

- Synchronizing Animation to Speech

- Lip-Sync—1

- Lip-Sync—2

- Lip-Sync—3

- Timing and Music

- Animating for Interactive Games

- Traditional Camera Movements

- 3D Camera Moves

- Peg Movements in Traditional Animation

- Peg Movements in 3D Animation

- Editing Animation

- Editing for Feature Films

- Editing for Children’s Programming

- Editing for Internet Programs

- Conclusion

- Index

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app