1

EMOTIONAL VOLUNTARISM

Suppose that a woman named Mary is suffering from rising anxiety. Mary is finding it difficult to let go of worries that she knows her husband will call ridiculous. She always has tended to be safe about things like turning off the oven or checking the doors at night. But her anxiety is making life progressively more difficult for her. As a wife and new mom, her mind is constantly occupied with worry, especially about unintentionally harming her child. She finds herself checking and rechecking safety issues like the car seat or the front door. The worries seem to come out of nowhere. She is too ashamed to communicate her anxieties to her husband, who might help steady her. She knows that her anxiety is causing strain on her marriage and fears that her husband will finally have it with her. He expresses exasperation over her worries—for example, that she will accidentally feed her child something toxic. He even sometimes uses the word “crazy.” She seems to be noticing that he is getting distant. How can we know what is happening here? Is this a pattern of sinful anxiety? Or might it be a psychological disorder? Is this the gradual late onset of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) as described by the DSM-V?1

For now, I want to draw our attention to the fact that we want to know where the anxiety is coming from. All pains leave us searching for causes because we think that identifying the cause can help us to treat the pain and to avoid future pain. Just as we might see an orthopedic surgeon to diagnose persistent knee pain, so also we see wise friends, pastors, counselors, doctors, and psychiatrists to diagnose psychological pain. We want to know what has gone wrong.

Because we want to understand psychological pain, it poses an introspective dilemma for many Christians. We tend to attribute the internal pain of anxiety either to sinful desires or beliefs, taking advice from the church, or to aspects of our experience that are out of our control such as inherited traits, traumatic experience, or disease, taking advice from psychology. A key aim for this book is to collapse this dilemma by modeling how our agency and experience (active and passive aspects) come together to produce emotion; genes, thoughts, actions, and experiences all contribute to emotional experience. In what follows, I will elaborate on the two poles of this introspective dilemma.

EMOTIONAL VOLUNTARISM

On one side of the introspective dilemma, we have a theological perspective on negative emotions. From a generically Reformed evangelical perspective,2 negative emotions have moral valence and can be right or wrong. In fact, emotions are crucial for true religion.3 Consequently, Reformed theologians often speak of our responsibility for emotions in terms of what I will call emotional voluntarism.4 We might summarize this view as follows: We are responsible for emotions as intrusive mental states that show what we truly believe. Moreover, the illicit desire or false belief may be overcome by applying the gospel through voluntary mental work.5 Briefly, emotional voluntarism includes the following elements:

(1)Emotion as judgment: Emotion is strictly or first a mental state.

(2)Emotions of the heart: Since emotions are morally significant, the proper subject of emotion is the heart, though perhaps some emotions are sourced in or influenced by the body.

(3)Deep belief associationism and legitimacy: Emotion is a mental state that arises when a deep belief is elicited into consciousness; the beliefs that surface unbidden are also our truest.6

(4)Mental voluntarism: Emotions as mental states are changeable by shifting attention, mainly through internal speech (e.g., repenting of false beliefs) to bring about new mental states.

(5)Emotional duty: People are duty bound to address any emotional aberrance as quickly as possible, since this is within their power.

I will briefly unpack these elements with examples. First, most recent Reformed evangelicals hold a cognitivist philosophical account of emotion. Emotion is a sort of judgment or construal of my state of affairs that expresses some sort of interest or attitude. For example, Matthew Elliott cites favorably the definition of philosopher William Lyons, “The evaluation central to the concept of emotion is an evaluation of some object, event or situation in the world about me in relation to me, or according to my norms. Thus, my emotions reveal whether I see the world or some aspect of it as threatening or welcoming, pleasant or painful, regrettable or a solace, and so on.”7 Robert Roberts has a nuanced version of this, calling emotions “concerned-based construals,” signifying that while emotions are cognitive (construal, judgments), they are also interested (concern-based, or valenced with respect to a judgment).8

Second, Reformed evangelicals commonly assume that emotions come from the heart, which is the soul and the center of human agency. Ed Welch is explicit about this. In Blame It on the Brain, he writes,

In the Bible, “spirit” (pneuma) shares its field of meaning with a number of words. Included are terms such as “heart” (kardia), “mind” (dianoia, phrenes, and nous), “soul” (Greek: psuche. Hebrew: nephesh), “conscience” (suneidesis), “inner self” (1 Peter 3:4), and “inner man” (2 Cor. 4:16). Even though these words have different emphases, they can be used almost interchangeably—and I will use them that way.9

Elsewhere Welch writes, “The differences between body and soul can be summarized this way: the soul is the moral epicenter of the person. In our souls or hearts, we make allegiances to ourselves and our idols or to the true God.… The body is our means of service in a physical world. It is never described in moral terms.”10 John Piper draws a similar distinction between the human heart and body. He writes, “The human heart does not replenish itself with sleep. The body does, but not the heart. The spiritual air leaks from our tires, and the gas is consumed in the day. We replenish our hearts not with sleep, but with the Word of God and prayer.”11 Piper does admit that the body in some way modulates the phenomenology of emotion,12 but at least spiritual emotion is not ultimately dependent on the body, since “presumably redeemed people will have strong emotions of adoration and satisfaction at God’s right hand after they die and before their bodies are raised from the dead (see Phil. 1:23; Rev. 6:10).”13 The assumption that the heart is the true source of emotion is also implicit in the common phrase that our emotions reveal our true beliefs.14 “Our emotion reveals truth about ourselves and our beliefs. The emotions of others or their lack of emotion often shows us what they think, value, and believe.”15 I do not have space to fully refute the claim that the heart is just the human soul in distinction to the body, metaphysically speaking. But this claim is not supported by an analysis of the biblical concepts lēv or kardia.16

Third, and relatedly, these accounts also involve a depth assumption about the heart where emotions are passively intruding mental states that come from the deepest source of our agency, especially implying the genuineness of deep belief versus the falseness of what we purport to believe on the surface. When emotion surfaces, it reveals our deep drives such that the true nature of the soul is revealed. For example, Brian Borgman writes, “the emotions … express the values and evaluations of a person and influence motives and conduct”; they “tell us what we really, really believe.”17 The implication is that we may be deeply mistaken about what drives us ultimately. Ed Welch visually represents this inside-out metaphor of agency as a heart inside a circle (Figure 1.1),18 where the “heart represents the soul, the circle represents the body.”19 The heart represents the source of our agency, thus the source of emotion, excepting certain purely bodily feelings.20

Figure 1.1, Welch’s Graphic of the Embodied Soul.

Fourth, if emotions are mental states, passively intruding mental states, emotional voluntarists tend to assume that by mere mental choosing, a person may alter mental judgments; I call this mental voluntarism. People may use internal speech to attack the propositional attitudes directly; or more indirectly, they may choose to channel their attention differently. For example, Brian Borgman writes, “I overcome anxiety by focusing on the consolations, the promises, you have given me in your Word.”21

Finally, emotional duty is the moral impetus for applying mental voluntarism to our occurrent emotional states. If I had thought or believed something different, I might have avoided this illicit emotion. I am now in a state of emotional culpability for my thought or unbelief. I might escape this culpability by choosing to think or believe differently. Therefore, I must now choose to think or believe differently. It is easy to see how this makes emotion morally relevant since this definition characterizes emotion as a sort of alterable mental state, which may or may not correspond to God’s revealed will. For example, to be anxious is to bring about or allow a certain sort of attitude grounded in the deep belief that God is not trustworthy (Matt 6:25–34) to give good things to his children (Matt 7:9–11).

A PSYCHOLOGICAL VIEW

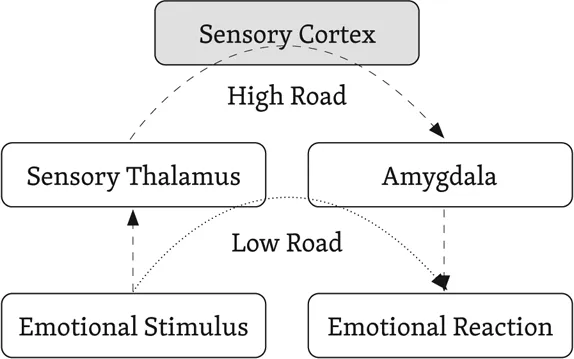

A psychological point of view is quite different. Consider Joseph LeDoux’s description of anxiety. This description is from his earlier work; we will address his more developed view in Chapter 8. LeDoux sees anxiety as what happens in the brain and nervous system. It involves a complex reaction system involving parallel brain transmissions “to the amygdala from the sensory thalamus and sensory cortex. The subcortical pathways provide a crude image of the external world, whereas more detailed and accurate representations come from the cortex.”22 LeDoux calls these parallel tracks the high road and the low road (Figure 1.2).23

According to LeDoux, the amygdala functions as a sort of “hub in the wheel of fear,” getting input from the sensory thalamus (stimulus features), sensory cortex (objects), rhinal cortex (memories), hippocampus (memories and contexts), and medial prefrontal cortex.24 The amygdala, in turn, activates the autonomic nervous system to adjust the body for the situation (e.g., heart rate, blood pressure, and adrenaline). These reactions of the body reciprocally reinforce the memory to automate future emotional responses to similar situations; adrenaline strengthens memories associated with emotional reactions. In sum, for LeDoux anxiety is a sort of fully bodily reaction that conditions us for future contexts. For LeDoux, to label this anxious reaction as “sin” is inappropriate because the bodily responses of anxiety are responses of unconscious processing; it is merely a legacy of evolutionary processes, which is largely outside of our control.25

Figure 1.2, LeDoux’s High and Low Road

Again, the two explanations of anxiety—one from theology and one from psychology—compete because they seem mutually eliminating. Moreover, choosing the right explanation is crucial for therapeutic recommendations; ontology underlies therapy. Each person will automatically adopt some explanation for the unwanted emotion. The explanation both helps us cope with the pain and governs strategy for coping. A significant benefit of counseling is reframing the story of what we are feeling. Counselors bring comfort because the way we explain our emotion to ourselves makes a great difference to how we experience it.26 Competing assessments of the nature...