eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Apr |Learn more

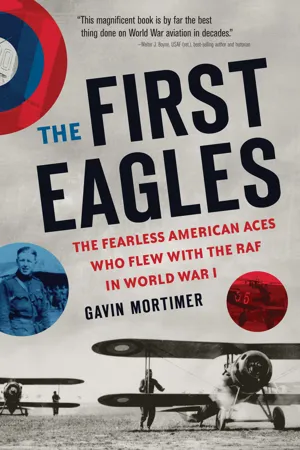

The First Eagles

The American Pilots Who Flew With the British, Became Aces, and Won World War I

This book is available to read until 23rd April, 2026

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Apr |Learn more

The First Eagles

The American Pilots Who Flew With the British, Became Aces, and Won World War I

About this book

An incredible history of the American WWI pilots who refused to be grounded.

There was a time when the United States didn't believe in aerial warfare. Wars, after all, were for men—not flying machines. When Europe went to war in the summer of 1914, the U.S. military boasted a measly collection of five aircraft, with no training programs or recruitment procedures in place. But that didn't mean the country lacked skilled pilots. In fact, it was just the opposite.

In The First Eagles, award-winning historian Gavin Mortimer engagingly profiles the restless, determined American aviators who grew tired of waiting for the their country to establish an aerial military force during World War I. It was these men who enlisted in Britain's desperate and battered Royal Flying Corps when, in 1917, it opened a recruitment office in New York. After an intensive and deadly year of training that gave recruits a frighteningly realistic taste of the combat they would face, 247 fresh American RFC pilots were shipped over to Europe, with hundreds more following in the next two months. Twenty-eight of them claimed five or more kills to become feted as "aces," their involvement lauded as pivotal to the Allied victory. In this book, Mortimer compiles their history through letters, diaries, memoirs, and archives from top museums in the United States and Britain—from John Donaldson, who left for France at age twenty and shot down seven Germans before being downed himself, to the Iaccaci brothers, who accounted for twenty-nine German aircraft between them. Complete with 150 period photographs, The First Eagles captures the bravery of these intrepid American pilots, who chose courage over idleness and saved the European skies.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The First Eagles by Gavin Mortimer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Histoire & Histoire de l'armée et de la marine. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

I’m Going to Tell Them I Raised Hell

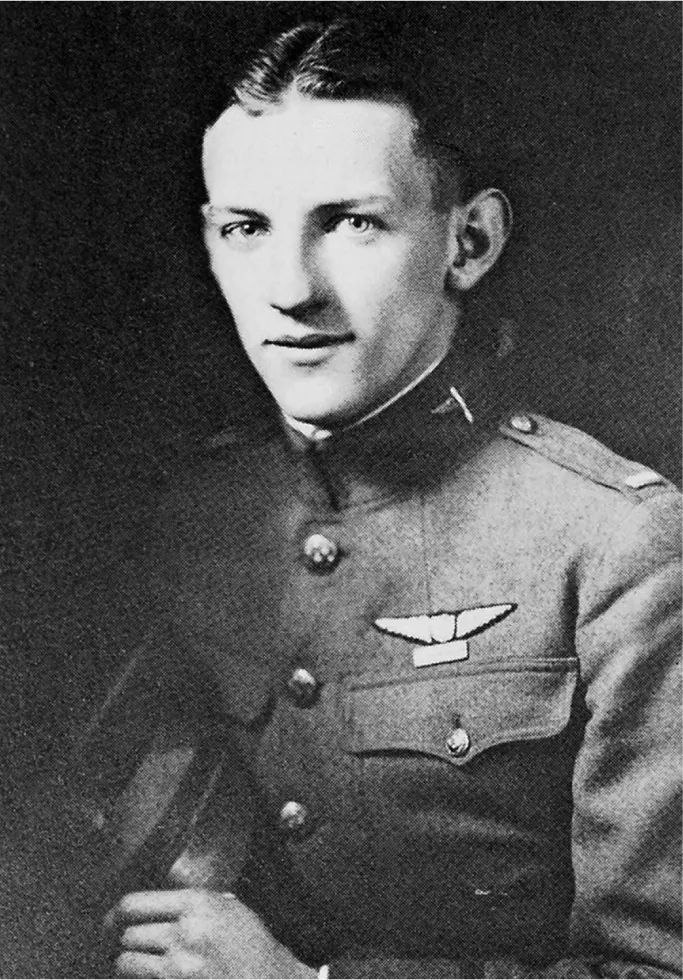

George Vaughn came from Brooklyn—from the Washington Avenue area, to be exact. Born in May 1897, he enrolled at Princeton University in 1915 and two years later put his name down for the fledging Aviation Corps. “They are organizing here,” Vaughn wrote his parents on February 7, 1917. “But [I] don’t know whether I will be able to get in it or not, as they are going to have examinations for nerves, endurance, etc.”

Vaughn had to wait a couple of months for his medical examination, by which time the Princeton Aviation School had been firmly established and war had been formally declared by Congress. “Committees composed of members of the Faculty and of the undergraduates were formed,” reported the Princeton Bric-a-Brac, the university’s undergraduate yearbook. “Several members of the Faculty volunteered to give lectures on the construction, operation and maintenance of an airplane motor…[and] towards the end of March came the gratifying announcement that sufficient funds had been collected and orders for two airplanes of the Curtiss JN-4B type of military tractor biplane were at once placed with the Curtiss Aeroplane Company.”

Vaughn underwent his physical examination in April, the doctor noting the cadet’s brown hair, blue eyes, and ruddy complexion in his file. Vaughn wrote his family on May 4 to explain that after undergoing the equilibrium and eye test, he had been subjected to a thorough medical “that has put a good many fellows out of the Corps. It was a physical examination such as I never even imagined before, and lasted over two hours and a half. You have to be practically perfect in every part of your body to get by, so I at least have the satisfaction of knowing that I am physically pretty well off.”

George Vaughn was an ace with thirteen victories who lived to be ninety-two. “All you had to do was fly the plane and shoot the guns,” he said modestly, shortly before his death.

Vaughn was one of thirty-six Princeton men out of more than one hundred volunteers who passed the medical, as was Elliott White Springs. “They are very particular about whom they take for the Aviation Corps and examine us very minutely,” Springs had written his father on May 1. “It’s the most exacting examination the Army gives. They spin you around on a stool, make you balance blindfolded, fire pistols behind you and all sorts of things like that.”

Springs confessed to his father that he’d feared his eyes might let him down—“as they only allow a small percentage of variations from normal”—but he passed the medical, unlike Arthur Taber, who failed his. Though an enthusiastic rower and member of the Princeton gun team, the portly young man lacked finesse and aggression. He didn’t lack connections, however, not with so wealthy and influential a father. The dean of the college, Howard McClenahan, wrote to the Aviation Corps to tell them of the student’s “strictest integrity,” while Taber also paid a visit to Washington “and called on a friend…a retired Brigadier-General, whose help in attaining this object he asked.”

At first the RFC resisted the pressure to accept Taber, but, finally, they relented and he was admitted into the Princeton Aviation School in July, by which time Vaughn and Springs and their thirty-four classmates were already accomplished aviators. “I can’t begin to tell you the wonderful fascination of flying and I enjoy it more every time I go up,” Springs wrote his father. “I had control of the plane yesterday for twenty minutes at an altitude of 4,000 feet and I don’t know when I enjoyed anything more.”

The students were taught in the Curtiss JN-4 biplanes on what Vaughn described as “a privately-operated field, located between Princeton and Lawrenceville,” and it was here that Taber joined them, if not trusted to take to the skies, then at least able to participate in “such subjects as theory of flight, internal combustion engines, machine guns, Morse code telegraphy, navigation, etc.” The students, most of whom had hitherto led lives of easy deportment, also encountered military discipline and close order drill for the first time. “All this drill was excessively tiresome and a dreadful bore,” Taber wrote his father on July 26. “…I sometimes regret that I did not join the naval aviation for in that branch now I could make a greater contribution to the Allied cause than where I am.”

Elliot White Springs beams for the camera after walking away unscathed from this flying accident in France.

With the six-week course complete and the cadets now “enlisted as Privates First Class in the Aviation Section of the Signal Corps,” the army faced the problem of what to do with them. “At that time there were no advanced flying schools in this country,” recalled Vaughn. “Fortunately for us, the Allies had started offering the use of their flying training facilities, so the army finally decided to send us abroad for advanced flying training.”

At the end of August the Princeton cadets were sent to Mineola flying field on Long Island, later the site of the Roosevelt Raceway, where they encountered cadets from other flying schools also waiting to embark overseas, some to France and others to Italy.

For Arthur Taber the stay at the Mineola airfield was his first exposure to the rich diversity of his country’s inhabitants. Reared in Lake Forest, Illinois, and schooled in Coconut Grove, Florida, the formative years of Taber’s young life had been spent in a privileged and serene environment. Earnest and studious, Taber entered Princeton, where he was a member of the university’s gun team, which contested an intercollegiate shoot with teams representing Dartmouth, Yale, and Cornell. This was the circle in which Taber felt comfortable: among the wealthy and well-educated, among America’s elite.

On August 28, his first evening at Mineola, Taber wrote his father, explaining: “This seems to be a concentration point for the men who are going to Italy: today a batch came in from Cornell. They are a clean-cut, military-looking lot, and I am rather heartened by their appearance. They are surely exceptional in being trim in appearance, for the average is very low, I regret to say.”

Taber had no issue with the Cornell men, nor with fellow Princetonians such as George Vaughn, Frank Dixon, Harold Bulkley, and Elliott Springs, even if Springs did have something of a wild reputation. At Princeton, he had spent much of his time striking a pose in his Stutz Bearcat, even driving the vehicle to Long Island when they were ordered to Mineola.

However, at least Springs—the son of a wealthy cotton-mill owner from South Carolina—had breeding. Taber wasn’t so sure of some of Springs’s acquaintances, budding aviators who had been ordered to Mineola from other flying schools across America. Clayton Knight, a native of Rochester, New York, and, at twenty-six, one of the oldest men at Mineola, was an artist who had studied under the iconoclastic modernist painter Robert Henri before enlisting in the military in 1917 and being sent to aviation school in Texas.

But if Knight was tainted by association in the eyes of Taber, John McGavock Grider was tainted, period. Born in 1892 at the family cotton plantation in Sans Souci, Arkansas, Grider—or “Mac” as he preferred to be called—had quit the Memphis University School aged seventeen to marry a fellow student, Miss Marguerite Samuels. To escape the scandal, Grider and his young bride retreated to the plantation, where she soon gave birth to two sons, John McGavock and George William. Neither Grider nor his wife adapted well to parenthood; he was working all hours on the plantation, and she found the responsibility too much to bear. The couple separated, Marguerite returning to her family in Memphis with the children, Grider throwing himself into his work. But he was still young and restless, and America’s entry into the Great War was the excuse he needed to flee Arkansas. Writing his family of his decision to enlist, he said: “Do you think I’m going to tell John and George when they get to be men that I raised cotton and corn during the war? Not by a damned sight, I’m going to tell them I raised hell.”

One of the “Three Musketeers,” Laurence Callahan was not just a brilliant ragtime pianist but also an ace with 85 Squadron and 148th Aero.

Grider was sent to the School of Military Aeronautics of the University of Illinois for aviation training, during which he wrote a friend back home of his first flight. “I have been up. God it is wonderful! I have never experienced anything like it in my life.”

Grider’s roommate was Larry Callahan, a tall, laid-back twenty-three-year-old from Kentucky who had curtailed a career in finance to serve his country. The pair hit it off straight away. Callahan was a gifted pianist and Grider loved to dance, the foxtrot being his favorite. They also shared a passion for liquor, women, and cards. Such pastimes were not the preserve of Taber. “I am not a prude about the question of drinking,” he wrote his father, “but I don’t like to see men take too much, first, because of the dire result of their actions upon themselves, and secondly, because someone else is sure to suffer, for some regrettable thing never fails to occur when one is temporarily and abnormally excited.”

Grider and Callahan were separated upon arrival at Mineola. Grider, like Taber, had volunteered for active service in Italy, while Callahan had been assigned to the contingent headed to France. The Italian detachment had as its cadet sergeant Elliott Springs, confident and strong willed despite having just turned twenty-one. A natural leader and a superb aviator, Springs was invested with the limited authority by the officer in charge, Maj. Leslie MacDill, with instructions to ensure the men did nothing to discredit America in the eyes of the watching world.

It was an onerous task for Springs, an exuberant and forceful personality whose character had been shaped in a large part by his prickly relationship with his domineering father. “I am opposed to your joining the aviation corps,” Leroy Springs had written his son in April 1917. “I do not feel that I should give my consent to it.” Aviation was the younger Springs’s escape from parental control, a joy he described in a letter to his stepmother as “the nearest thing to the Balm of Gilead I know.”

But there were other balms in Springs’s life: the same pleasures enjoyed by Grider. At Mineola, Grider discovered that Springs played bridge and liked music, so he told him, “I have a friend over here at this other place that’s a good bridge player and plays the piano. You better get him over here.” The friend in question was Callahan. Springs did as requested, arranging the transfer of Callahan to the Italian detachment of aviators. The three young men complemented each other: the blond, handsome Grider, the eldest of the three but with an infectious boyish enthusiasm for life; Springs, who looked like a boy, his face unmarked by toil or trauma, but whose personality was more complex than either Grider’s or Callahan’s; and Callahan, who asked himself fewer questions than his two friends and just got on with life, taking its vagaries in his languid stride. Before long the trio were calling themselves “the Three Musketeers.”

A reporter from the New York Times ventured to Mineola to spend several days in the company of the cadets and captured the tedium felt by many of the raw recruits in an article entitled “Long, Weary Waiting for Airplane Student.” “The first sight of the high board inclosure [sic] of the flying field brings a distinct thrill,” wrote the correspondent. “But after sitting in barracks day after day, fingering brand-new equipment, cleaning brand-new pistols, hearing the airplanes of the fortunate buzz by overhead, ever and again sneezing in the plentiful dust—that yellow Long Island dust which rises so thickly when the ground is scratched that even the general’s car must slow down on the high road—well, that thrill wears off.”6

As for the cadets who sat listlessly in the classroom, desperate to fly but damned to spend hour after hour studying theory, the reporter from the New York Times sympathized with their plight, writing: “The men who have volunteered for training in Italy are in a curious state of mind. They have no idea of where they are going or of what is going to happen to them when they get there; but they are perfectly sure that it will be the best possible. No one has been sent to Italy for flying training yet, or at least no one has been there long enough to send back word what it is like, and these men will be the first in that particular field, pioneers, explorers. And that is enough.”

On Sunday, September 16, 1917, Major MacDill ordered Springs to tell “everyone to get rid of their cars” except for Springs himself and to “place sentinels around the barracks to keep anyone from leaving even for a few moments.” MacDill and Springs then drove into New York to “arrange the final details” of their embarkation for Europe, and the following day, September 17, Springs deposited his treasured Stutz at the Blue Sprocket garage with instructions for it to be returned to the manufacturer. Springs then drew some money, dined out at a fashionable restaurant, and returned to Mineola at 2:00 a.m. “to find special orders waiting on me to have breakfast at 4:30 and be ready to break up camp at 6:30.”

A Curtiss-Herring at Mineola airfield in the early days of aviation. Library of Congress

Springs did as instructed, and at 7:00 a.m. on Tuesday, September 18, he and approximately 150 other cadets boarded a train bound for Long Island City. Once they arrived, remembered George Vaughn, they were taken on a tugboat to SS Carmania of the Cunard Line. “Since there were not supposed to be any troops abroad, we were boarded via rope ladders on the river side, where we could not be seen from the dock.”

Carmania wasn’t the first vessel to transport American aviators across the Atlantic to Europe. A month earlier RMS Aurania had sailed from New York to Liverpool with a detachment of fifty two cadets under the command of Capt. Geoffrey Dwyer, including 1st Lts. Bennett Oliver and Paul Winslow, both of whom had been obliged to take their turn on watch, their eyes scanning the gray ocean for signs of dreaded German submarines. Half an hour before midnight on August 30, Winslow had spotted a light in the distance. “It was Ireland,” he wrote in his diary, “and nothing ever seemed so good as the sight of something indicating land, as it meant we were safe once more.”

The mood among the second contingent of American flyers destined for Europe was carefree; the men were unconcerned by the prospect of submarine attack. After nearly three weeks of being stranded at Mineola they were finally on their way to war, and wrapped tight around them as they scaled Carmania’s rope ladders was the invincibility of youth.

Carmania, launched in 1905, was the pride of the Cunard fleet, powered by steam turbines with a speed of eighteen knots. The aviators were shown to their quarters in first class along with a handful of civilian passengers, some army officers, and forty Red Cross nurses. “The boat we have is a very good one,” wrote Vaughn to his family. “There are a lot of regulars with us, mostly infantry, and all riding in the steerage, and I guess it is not too pleasant down there.”

For Vaughn and his fellow aviators, however, the voyage was “just like a vacation trip for us; lots of sleep, excellent food, deck chairs and all our time to ourselves.”

Once she left New York on Tuesday, Septem...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Contents

- The Flyers

- Introduction A Useless Fad

- Chapter 1 I’m Going to Tell Them I Raised Hell

- Chapter 2 The Suicide Club

- Chapter 3 The King and the Cowboy

- Chapter 4 Aren’t We Ever Going to Fly?

- Chapter 5 The Cream of the Cadets

- Chapter 6 The Red Baron’s Last Fight

- Chapter 7 Love and War

- Chapter 8 Dogfighting Days

- Chapter 9 Am I to Blame?

- Chapter 10 From Toronto to the Trocadero

- Chapter 11 Chills Down My Spine

- Chapter 12 Why Are You Crying, Sir?

- Chapter 13 I Am an Old Man

- Chapter 14 Low-Level Terror

- Chapter 15 The 17th Aero Squadron

- Chapter 16 Nerves Worn to a Frazzle

- Chapter 17 Killed Doing Noble Duty

- Chapter 18 Peace on the Horizon

- Chapter 19 There I Lived a Life

- Chapter 20 Homecoming

- Epilogue All You Had to Do Was Fly the Plane

- Appendix I The Fate of the Few

- Appendix II The Planes

- Bibliography

- Index

- Footnotes

- Dedication

- Copyright