![]()

1

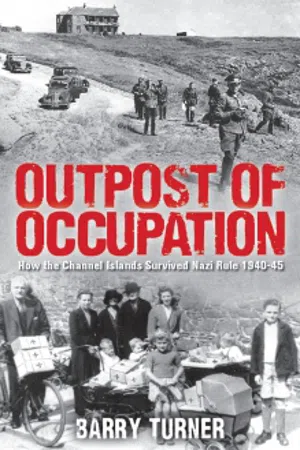

A SHOCK TO THE SYSTEM

Everywhere the flags were flying, but this was no celebration. The improvised banners flapping in a summer breeze were a uniform white and the message they conveyed was the same for every house and farm in Jersey. The Germans were coming and there was absolutely nothing anyone could do about it.

The date was 1 July 1940. It had happened so quickly. Two months earlier Hitler’s army had been poised but was yet to strike. In London, there was confident talk of defending the Channel Islands if, and this was judged to be highly improbable, a German invasion was threatened. Then, starting in April, events unfolded with dramatic suddenness. First Denmark and Norway were overrun. Belgium and Holland soon went the same way. On 4 June the last British soldier was lifted from the beaches of Dunkirk and two weeks later, on Monday, 17 June, France finally crumbled before the German military machine. The whole of the coastline of north-west Europe, from north of Norway to the Spanish frontier, was now in German hands.

The shock to the people of Jersey and Guernsey and of their smaller neighbours, Alderney and Sark, was profound. Living as they did closer to France than to England (Jersey is just fifteen miles off the French coast and Alderney even closer), many islanders were more familiar with St Malo, Granville and Cherbourg than Plymouth, Southampton and Bournemouth. Though their first loyalty was to the British crown and had been since 1066, even those who did not have friends and relatives across that narrow strip of water shared France’s pain and humiliation. There was fear too. Gunfire could be heard; the smoke from blazing oil depots was clearly visible. How long would it be before the enemy was at the gate?

*

Between the world wars, the Channel Islands were the places to go to get away from it all. Sea, sand and sunshine appealed to British holidaymakers, who enjoyed a touch of joie de vivre without the trouble of passports and currency exchange. The travel guides were characteristically euphoric, promising ‘spectacular coastlines, rugged cliffs, golden beaches, secluded coves and green hills’ with ‘warm, invigorating days from April until October’. As the largest of the islands, with a population of just over 50,000, Jersey’s average daily sunshine was touted as higher than that of any other British resort. Conditions were thus eminently suitable for those ‘of advanced years or of delicate constitution’. But to get there they had to endure a nine-and-a-half hour sea crossing from Southampton or Weymouth, often over choppy water. On one gale-swept occasion, the journey to St Helier, with stopovers in the Solent and at Guernsey took sixty-two hours.

Though Jersey airport was not opened until 1937 (with Guernsey’s following two years later), air services began as early as 1933, with the newly created Jersey Airways using West Park Beach as an airstrip. This ‘beach aerodrome’ was said to be the first to be submerged twice a day and to have its timetable controlled by the tides. In the first year of operation over 20,000 passengers were carried. (Today, the figure is well over 1½ million.) By 1939, there were daily services to Jersey and Guernsey with an inter-island hop from Jersey to Alderney. On the main routes, the journey time was soon little over an hour, an advance in communication which promised a healthy expansion of tourism.

While English was the predominant language, French was still used by government and law, though the patois spoken by the farmers (Jérriaise in Jersey, Guernesais in Guernsey and Sercquiaise in Sark) was incomprehensible to anyone schooled on the canons of the Académie Française. The image of gentle living, attractive to well-heeled retirees in pursuit of a low tax regime as much as to tourists and long-stay residents, was reinforced by the seasonal appearance of luxury produce on British tables – butter, cream and new potatoes from Jersey, flowers and tomatoes from Guernsey.

But for the citizens of the Channel Islands who had to make a living from the land and sea, the cosy rural idyll was not all that visitors cracked it up to be. Basic services such as electricity and piped water were restricted to the most prosperous homes. On the tiny island of Alderney there were just seven pumps to provide fresh water for around three hundred residents; the only generator was used to power dockside lifting gear. Life was less harsh on Jersey and Guernsey but to eke out a precarious living from the land many farmers took to their fishing boats from May to September, often crossing the Atlantic to share in the catch of Newfoundland cod. Motor vehicles were heavily outnumbered by horse-drawn traffic (even today no cars are permitted on Sark) and it was with no sense of irony that Guernsey adopted the donkey, used for dragging goods up the steep, cobbled streets of St Peter Port, as a national symbol.

Though attached to the British crown, the Channel Islands were almost entirely free from ministrations of the British government. For this unique state of affairs, the islanders had to thank the Duke of Normandy, their protector in 1066 when he made his successful bid to occupy the throne of England. When the Norman Kingdom broke away in 1204, the islands remained crown properties, appropriately known as ‘peculiars’. Jersey and Guernsey had parliaments, known as The States, elected on a property franchise. Each was led by a bailiff who was also the chief magistrate. Alderney had its own government while Sark, though left largely to its own devices, was a dependency of Guernsey. The official channel of communication with London, responsible for diplomacy and defence, was between the Home Office and the relevant lieutenant-governor and commander in chief, both royal appointments, based in Jersey and Guernsey.

With duties that were more ceremonial than political, these officers of state with their grand titles seldom had reason to bother their masters in Whitehall. Their first point of contact was Charles Markbrieter, the assistant secretary at the Home Office responsible for Channel Islands affairs. Little is known of Mr Markbrieter but we can imagine him, a dedicated civil servant at the pinnacle of his modest career, trying to come to terms with the dramatic change of tone in the correspondence that routinely passed across his desk.

The lieutenant-governors wanted to know what action they were supposed to take to meet the possibility of a German attack, a reasonable inquiry which went unanswered until the pecking order between the Home Office and the War Office, both acutely conscious of status, had been clarified. In true bureaucratic tradition, this took some time, and it was several weeks before the two departments of state agreed that the War Office could talk directly with the lieutenant-governors without first seeking Home Office approval.

Not that this did much immediate good for the Channel Islands. In September 1939, a military shopping list including two coastal defence guns, four anti-aircraft guns and twelve Bren guns, ended up in a War Office pending tray, where it remained until the weapons were no longer needed. Meanwhile, on their own initiative, the lieutenant-governors did what they could to bolster the islands’ defences by summoning able-bodied men to their local militias. Many of those who were eager to sign up subsequently volunteered for the British armed forces, while others were netted by conscription. This left the Royal Guernsey Militia and Jersey’s Insular Defence Corps at a state of readiness equivalent to a Dad’s Army with ancient weapons and a near absence of experienced officers. A Jerseyman on guard duty on the promenade at West Park found himself sharing a rifle with two comrades. They had five rounds of ammunition between them. ‘It was a strange thought,’ he recalled, ‘that the Germans were a few miles away at St Malo, Granville, Carteret, that their Luftwaffe could have blown our island out of existence in a few minutes.’1

A few British troops did little to inspire confidence. Much against his will E.V. Clayton found himself posted to Alderney, the 2,000-acre island only ten miles from the French coast. He was billeted in Fort Albert, one of a series of fortifications built in the early nineteenth century to repel attacks by Napoleon’s army. Nothing much had changed since then. Rooms were lit by hanging oil lamps, the walls were damp and iron-frame beds with straw mattresses defied sleep. Apart from some new Bren guns, all their weapons were of First World War vintage.2

In the early months of 1940, the question of how the Channel Islands fitted into the broader strategy of defending the entire country was still a source of contention and confusion. Since any surrender of territory was bound to damage morale, the vulnerability of the islands had to be taken seriously. But the chiefs of staff were at a loss to know what to recommend. Even in late May, when the fall of France became a real possibility, they seemed none too sure of the precise location of each of the islands or to know anything about their history. A briefing document tabled on 5 June led off with a lengthy account of how they came to be part of Britain, with a summary of their military contribution to long-past Gallic skirmishes. Thus educated, the chiefs of staff tried to read the German mind. The likelihood seemed to be that if the German army succeeded in taking the north coast of France, it would almost certainly make the jump over to the islands. Little could be done to stop this. However, the briefing note suggested, ‘once in occupation … the difficulties of maintenance, though not insuperable, would make his position precarious’. The anticipated action was thus a raid by troop-carrying aircraft and fast motorboats followed by a strategic withdrawal.

This left open various counter-moves including a demilitarisation of the islands, the least favoured option while the French were still fighting: ‘We might be accused of exposing the French Northern flank to a further scale of attack from bases in the islands’. The compromise, since ‘measures to ensure the security of the islands against all possible scales of attack would not be justified’, was to bolster existing defences, in themselves barely adequate for token resistance, with two infantry battalions, one stationed in Jersey, the other in Guernsey.3

The other major recommendation was ‘the evacuation of all women and children on a voluntary and free basis’. The prospect of a total evacuation was discounted for three reasons – inability to provide air cover to a large number of ships, the difficulty of coping with reluctant evacuees and, thirdly, startling in the brutality of the language, ‘we have already too many useless mouths in the United Kingdom’.4 It was clear that the chiefs of staff were not likely to be swayed by sentiment.

The report was considered and approved by the War Cabinet on 12 June, with Neville Chamberlain, as Lord President of the Council, presiding.5 The battalions were put on standby. But no sooner was the decision taken than it was challenged. Later the same day, when the War Cabinet reconvened, Churchill, who had become Prime Minister on 10 May, was in the chair but made no comment when Anthony Eden, Secretary of State for War, asked that the matter of sending two battalions to the Channel Islands be reconsidered. With the now near certainty that the French coast would soon be in enemy hands, the idea that the so far unbeatable Werhmacht could be deterred by a couple of hundred ill-equipped Tommies was clearly absurd. In any case, what precisely was being defended? The underwater telephone cable link to France would be of no further use when the Germans were listening on the other end of the line. As for their strategic value, the islands could play no significant role in the defence of Britain, while from the enemy’s point of view they were, at best, a depot for attacks on the mainland. Fortunately, perhaps, neither Jersey nor Guernsey was in the forefront of modern communications. Their harbours were not equipped to receive a naval armada, while the airports were barely able to cope with tourist traffic.

But if the defence of the islands could not be justified, practical politics, let alone humanitarian considerations, ruled against simply abandoning fellow countrymen. More thought was given to declaring the islands a demilitarised zone, a strategy proposed by the chiefs of staff on 13 June and confirmed in a paper for the War Cabinet five days later.6

Meanwhile, the frustration of the lieutenant-governors was palpable. Their only firm instruction from London was to assemble a fleet of small boats to help in the evacuation of British troops from St Malo. This they did with commendable speed and efficiency, with the major contribution coming from Jersey, as the island closest to the action. As troops stationed on the islands began to leave, the absence of any official announcement stretched the nerves of the civil population. Confusion was greatest in Alderney whose chief administrator, Judge Frederick French, had no direct link with London and only sporadic contact with Jersey and Guernsey. Adopting the advice of the senior army officer on the island, he concluded the Sunday church service by assuring the congregation that there was no need for alarm, that everything was under control. The departure of British troops and the arrival of exhausted and demoralised French soldiers and sailors, escapees from Cherbourg, suggested otherwise.

The islanders might have been a little comforted had they known that they were not the only victims of shambolic planning. At this point in the war, when bad news was a daily occurrence, the entire British military and civil command structure was in danger of collapse. General Sir Alan Brooke, soon to be Chief of General Staff, noted in his diary, ‘History is repeating itself in a most astonishing way. The same string-pulling as in the last war, the same differences between statesmen and soldiers, the same faults as regards changing key posts at the opening of hostilities, and now the same tendency to start subsidiary theatres of war, and to contemplate wild projects!’7

Churchill was already prime minister but had still to assert his unassailable authority as war leader. Maybe the Channel Islands should be grateful that he was still feeling his way, for the view from 10 Downing Street was that British territory should be defended to the last man. ‘It was repugnant,’ he argued, ‘to abandon British territory which had been in the possession of the Crown since the Norman Conquest.’ It took an angry session of the War Cabinet and the persuasive powers of the Vice-Chief of Naval Staff to prove to Churchill that to do battle over the islands was to invite a massive loss of ships, planes and civilian lives.8

Churchill gave way, enabling the War Office to reveal its plans for demilitarisation. But it did so half-heartedly. German intentions were still unclear, and any action on the Channel Islands might have been seen as premature. On 19 June orders were sent to the lieutenant-governors to prepare for their own imminent departure and of what was left of their military establishments, but no one thought fit to inform the citizenry or, more to the point, to tell the Germans that the islands were undefended. This omission was later rationalised as a delaying tactic to deter the enemy from moving in before a civilian evacuation had been organised. In reality, the problem was one of communication between the three departments of state – Home, War and Foreign – each claiming an interest in the immediate future of the islands.

Ordered to stay at their posts, the two bailiffs, Victor Carey on Guernsey and Alexander Coutanche on Jersey, were now in sole charge. It must have been an awesome moment for both when they realised the weight of responsibility thrust upon them. Coutanche was best prepared for the ordeal. A politician and lawyer in his prime, he kept his nerve. Carey was a weaker character, used to being a figurehead more than an active leader. Though holding on to his title, he was soon to be supplanted.

The last of the troops based on Guernsey and Jersey left by midday on 20 June, and the lieutenant-governors followed the next day. As they departed, work started on cutting the cable to the French mainland. A press announcement on demilitarisation, prepared by the Home Office, was ready for release on 22 June but held back, probably by the Foreign Office, on instructions from Downing Street. Instead, a message from Buckingham Palace was sent to the bailiffs, assuring them and ‘my people in the islands’ that their best interests were being served by the withdrawal of armed forces. The King had no doubt that the islanders ‘will look forward with the same confidence as I do to the day when the resolute fortitude with which we face our present difficulties will reap the reward of victory’.

This ringing declaration of sympathy and support might have had more impact if it had not been accompanied by a letter from the Home Secretary urging discretion, on grounds of national secu...