ARMY

Major Robert Rogers

Robert Rogers (November 7, 1731–May 18, 1795) was an American colonial frontiersman and skilled woodsman. During the French and Indian War, Rogers assembled and commanded Rogers’s Rangers, a band of mountain men skilled in fieldcraft, wilderness skills, and shooting. Rogers trained his Rangers to be a rapidly deployable light infantry force for reconnaissance and direct raids against the enemy.

The Rangers fought for the British, using the techniques and tactics of the American Indians. They conducted long-range reconnaissance patrols across difficult terrain in poor weather conditions that would have hampered local militias in special operations raids against distant French targets. Major Rogers did not invent unconventional warfare, but he was able to exploit tactics and establish them in Ranger doctrine; his “Rules for Ranging” comprise twenty-eight tenets for commanding such units.

A simplified set of the rules is still taught to US Army Rangers, who today claim Rogers as their founder. Rogers’s “Standing Orders” are still quoted on the first page of the US Army Ranger Handbook. The first rule? “Don’t forget nothing.”

“Brown Bess” Carbine

While they were winning fame during the French and Indian War, the primary weapon of choice for Rogers’s Rangers was the “Brown Bess.”

The Long Land Pattern musket was the British infantryman’s basic arm from about 1740 until the 1830s. A challenge to carry through the woods, the 1742 Long Pattern 1st Model musket was often cut down several inches, resulting in a Brown Bess carbine. The musket had a flintlock action and weighed 10.5 pounds. It fired a .75-caliber ball with an effective firing range of 50 to 100 yards.

Jäger Rifle

The standard rifle of Rogers’s Rangers was the Brown Bess, but some in the band carried the German Jäger rifle, a flintlock, muzzle-loading musket with an average length of 45 inches. It weighed 9 pounds and was fitted with a 30-inch barrel. In most cases, individual Rangers used Jägers as their personal weapon, which meant each had a unique character. A trigger guard for improved grip or a raised cheek rest to help aim might be found on some examples of this rifle. The Jäger was an accurate rifle, though it took longer to load than the Brown Bess.

Tomahawk

The hatchet was a useful tool for fieldcraft and chopping wood. In the hands of Rogers’s Rangers, this general purpose tool turned into a lethal weapon. Taking a lesson from American Indians, Rogers’s men carried tomahawks along with their muskets. The wooden handle of the “hawk,” as it was called, averaged 18 inches. One end of the head had a hardened spike, while the other had a chopping blade that was to be kept honed at all times.

The hawk was a formidable weapon. It could be thrown with deadly precision and, in hand-to-hand combat, gave the Ranger an extended reach. This weapon could be used to slash at the enemy’s torso, neck, or extremities, while the sharpened point could be used to puncture a skull and the pommel (handle end) could be modified to deliver a fatal blow. The crook of the hatchet could be used to hook and restrain an attacker’s arm.

The tomahawk was hands-down an integral weapon in Rogers’s Rangers’ mobile arsenal. In fact, tactical tomahawks have found their way into the kits of many special-ops soldiers today.

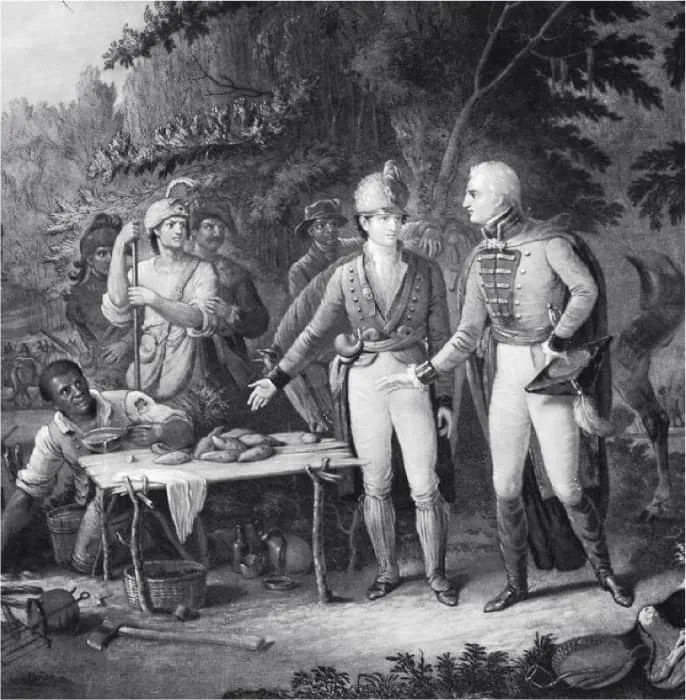

General Francis Marion, the “Swamp Fox”

Born and raised in South Carolina, Francis Marion fought the Cherokee in 1760 as a lieutenant in the state’s militia. During the Cherokee War, Marion learned Cherokee fighting techniques, including the tactic of initiating surprise attacks and then quickly fading away.

During the Revolutionary War, Marion received a commission as captain in the Continental Army and took up arms in the fight for freedom. He brought guerrilla war tactics against the British, establishing his position in the Special Forces lineage. When Charleston fell to the British, General Marion escaped capture and headed into the South Carolina swamps, where he established a base camp and, with 150 men, formed what would become known as Marion’s Brigade. As the war progressed, the brigade employed unconventional warfare tactics against the British, ambushing troops, attacking supply lines, and performing hit-and-run raids. Try as they might, the British could not follow these guerrillas into the swamp, earning Marion his famous nickname.

Flintlock Pistol

Although surprise was the Swamp Fox’s primary weapon, there’s no doubt his band of guerrillas took advantage of the weapons they captured. The standard-issue sidearm of the British Army during the Revolutionary War was the Tower Model 1760 flintlock pistol, which fired a .67-caliber musket ball. Originating in the Tower of London—the site of the British arsenal as well as the infamous prison—the weapon was assembled by gunsmiths according to the British Army’s strict specifications. In the colonies, guerrilla fighters often carried one or two of these tucked into their belts, ready for battle.

Colonel John Singleton Mosby, “the Gray Ghost”

Mosby’s Rangers were one of the most celebrated units to practice unconventional warfare during the American Civil War. Under the command of Colonel John Singleton Mosby of Virginia, these Confederate guerillas operated behind the Union lines just south of the Potomac. Colonel Mosby began with a three-man scout element in 1862; by 1865, his Rangers had evolved into a force of eight guerilla companies.

A firm believer in reconnaissance, aggressive action, and surprise attacks, Colonel Mosby and his Rangers cut off Union communications and supply lines, sabotaged railroads, and raided base camps behind the enemy lines. His stealth and uncanny ability to avoid capture earned the colonel his nickname. Mosby’s Rangers were well trained and well disciplined, setting a standard for future unconventional forces to follow.

Kentucky Long Rifle

A rifled gun barrel uses spiral grooves to give a lead ball a spinning motion, resulting in better accuracy than a smoothbore musket. The Kentucky long rifle, an early example of a rifled-barrel weapon, weighed 18 pounds, with a bar...