Universal Principles of Art

100 Key Concepts for Understanding, Analyzing, and Practicing Art

- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Universal Principles of Art

100 Key Concepts for Understanding, Analyzing, and Practicing Art

About this book

A follow-up to Rockport Publishers' best-selling Universal Principles of Design, a new volume will present one hundred principles, fundamental ideas and approaches to making art, that will guide, challenge and inspire any artist to make better, more focused art.Universal Principles of Art serves as a wealth of prompts, hints, insights and roadmaps that will open a world of possibilities and provide invaluable keys to both understanding art works and generating new ones. Respected artist John A. Parks will explore principles that involve both techniques and concepts in art-making, covering everything from the idea of beauty to glazing techniques to geometric ideas in composition to minimalist ideology. Techniques are simple, direct and easily followed by any artist at any level. This incredibly detailed reference book is the standard for artists, historians, educators, professionals and students who seek to broaden and improve their art expertise.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

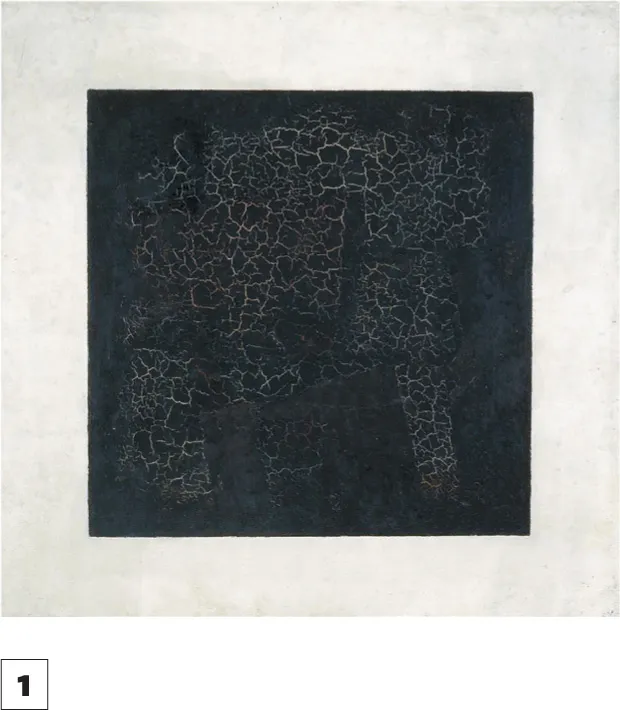

1 ABSTRACTION

Black Square on White Ground, 1915, Oil on linen, 31 5/16 × 31 5/16 in (79.5 × 79.5 cm)

Improvisation 27 (Garden of Love II), 1912, Oil on canvas, 47 3/8 × 55 1/4 in (120.3 × 140.3 cm)

2 ALLEGORY

Allegory of Age Governed by Prudence, 1565–70, Oil on canvas, 30 × 27 in (76.2 × 68.6 cm)

3 AMBIGUITY

VARIETIES

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Preface

- Contents

- Introduction

- 1 Abstraction

- 2 Allegory

- 3 Ambiguity

- 4 Appropriation

- 5 Areas of Competence

- 6 Authenticity and Outsider Art

- 7 Autobiography

- 8 Balance

- 9 Beauty

- 10 Boundaries

- 11 Brush Techniques

- 12 Chance

- 13 Classicism and Renaissance

- 14 Collage and Assemblage

- 15 Color as Light

- 16 Color as Limit

- 17 Color Theory

- 18 Composition

- 19 Conceptual Art

- 20 Consistency of Visual Language

- 21 Craft

- 22 Creativity

- 23 Cross-Cultural Fertilization

- 24 Cubism

- 25 Dada

- 26 Decoration

- 27 Distortion

- 28 Distribution

- 29 Drawing Language

- 30 The Emotive Object

- 31 Erotic Art

- 32 Expression in the Abstract

- 33 Fantasy and Visionary Art

- 34 Finish

- 35 Formal Innovation

- 36 Form Rendered

- 37 Gender

- 38 Harmony

- 39 Hierarchical Proportion

- 40 Imagination

- 41 Installation

- 42 Intentionality

- 43 Interactive Art

- 44 Juxtaposition

- 45 Kinetic Art

- 46 Land Art

- 47 Layers

- 48 Linear Basics

- 49 Mannerism

- 50 Mass

- 51 Materials as Art

- 52 Minimalism

- 53 Mixed Media and Multimedia

- 54 Motif

- 55 Movement

- 56 Narrative

- 57 Op Art

- 58 Overload

- 59 Performance Art

- 60 Perspective

- 61 Plasticity

- 62 Politics and Polemics

- 63 Prepare and Develop

- 64 Printmaking

- 65 Process as Meaning

- 66 Proportion and Ratio

- 67 Quality

- 68 Quoting

- 69 Readymades

- 70 Realism

- 71 Religiosity

- 72 Repetition

- 73 Representation

- 74 Restraint

- 75 Rhythm

- 76 Romanticism

- 77 Scale

- 78 Semiotics

- 79 Semiotics 2: Deconstruction

- 80 Sensitivity and Sensibility

- 81 Shape

- 82 Shock

- 83 Simplification

- 84 Space and Volume

- 85 Spectacle

- 86 Style and Stylishness

- 87 Successive Approximation

- 88 Sufficiency of Means

- 89 Surrealism

- 90 Symbols

- 91 Symmetry

- 92 Temporary Art

- 93 Texture

- 94 Theme

- 95 Tone as Structure

- 96 Touch Communicates

- 97 Tribal Art

- 98 Trompe l’Oeil

- 99 Underpainting

- 100 Video Art

- Credits

- About the Author

- Acknowledgments

- Copyright