![]()

Part One

Triumph

Oh, nefarious war! I see why arms

Were so seldom used by benign sovereigns

Li Po, 8th Century

![]()

Prologue

Strangers in the Night

Welcome tae yer gorie bed

Or tae victorie!

Robert Burns

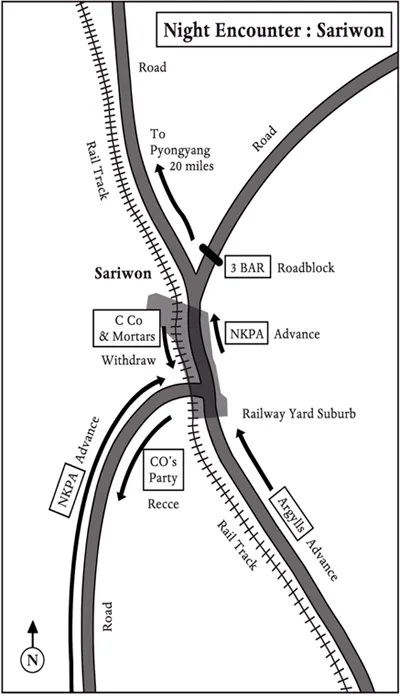

15:20, 17 October. Western axis of advance.1

Bright, late afternoon sunlight bore down. On the hard-baked dirt track south of the town, the line of tanks, trucks and jeeps ground to a halt. Perched on the vehicles, soldiers in faded combat uniforms peered ahead. Engines idled. Clouds of mustard-coloured dust billowed into the air behind the stationary column. Officers raised field glasses and focused on the town ahead.

Sariwon. Another grid reference, another town, another target on the advance up this blighted peninsula. Dominating a key crossroads on the highway to Pyongyang, the enemy capital, it was an industrial centre and communications hub. Sariwon. It did not look like much. Scanning through binoculars, officers could see the railway suburb south of the town proper, and beyond it, streets lined with the ubiquitous wooden telegraph poles threading through a conglomeration of traditional Korean cottages, utilitarian concrete buildings and warehouses – even a spired church. But it was not what it had been just months ago. War, in the shape of B-26 bombers, had visited. Many buildings were mere shells, empty holes smashed from the sky. Sariwon.

Silhouettes broke the skyline on a ridge overlooking the town. Enemy. Machine guns on tank turrets barked. The silhouettes disappeared.2 Signallers spoke into radio mikes. Orders were passed along to platoons, sections. Sherman tanks clattered and squeaked as they took up positions. Infantrymen, bulky with canvas bandoleers and stuffed ammunition pouches, dropped heavily from the vehicles, brought weapons into the ready position and fanned out into assault lines.

In their first major action a month earlier, these soldiers had suffered a disaster that had wiped out a company. Then, they had choked on the dust hurled up as their American allies led the advance. Now, they were the spearhead, the vanguard of the United Nations’ war machine as it stabbed into enemy territory. Would the town be a fortress? It was the last major obstacle before the Pyongyang plain. Senior officers expected ‘a big fight’.3 Casting long afternoon shadows, 1st Battalion, Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, descended upon Sariwon.

Fighting in built up areas is the most nerve-wracking form of combat. Every street is a valley, dominated by rooftops; every building a potential strong point. Every window can hold a sniper, every doorway, a booby trap. C Company advanced up the main road. Private Ronald Yetman – an Englishman, who at 6-foot, was, like many of the bigger Argylls, a Bren gunner – moved warily. Occasional rounds – sniper fire – cracked overhead, but the advance continued; trained soldiers only halt when fire becomes effective or when they hit resistance. Nothing. The town, like so many others, was eerily empty.

Tension evaporated. Yetman and his mates relaxed into covering positions while B Company’s commander, Major Alastair Gordon-Ingram, and his second-in-command, Captain Colin Mitchell, carried out a short vehicle recce. Meanwhile, trucks and tanks crowded with grinning infantry in broad-brimmed hats rumbled by: 3rd Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment was passing through to set up a block to the north. Soon it was quiet again.

A Company, which had fought a sharp action on Sariwon’s outskirts, arrived. Their OC, Major David Wilson, slumped into the chair of a deserted barbershop, its walls lined with tall, American-style mirrors. It was an unexpected find in this half-ruined town – particularly for an officer who had been living in the field for weeks. Outside, the B Company officers had just returned from their recce when their battalion commander, Lieutenant Colonel Leslie Neilson, drove up and called them over. The three were conferring over maps in the middle of the street when a truck drew up alongside and halted, apparently to ask directions. The conversation was stillborn; the realisation hit all participants at the same moment.4 The vehicle was bristling with armed enemy.

Around Wilson, the barbershop mirrors disintegrated into crystal fragments. A crescendo of North Korean fire – the ripping ‘brrrrrppp’ of PPsh 41 submachine guns – was amplified by the close walls. Outside, with bullets whipping overhead, Neilson abandoned his vehicle and dived behind a low wall. As he attempted to return fire, he was struck by one of those embarrassments that is not meant to affect colonels: His Sten gun jammed. Gordon-Ingram was having more success: Standing upright next to the land rover, ‘looking exactly like the sheriff in an old-time Western’, he picked off enemy with carefully aimed shots of his revolver.5 By now, Yetman and his mates had reacted. Bullets hammered through the bodywork of the vehicle, coverless in the centre of the road. North Koreans vaulted off the truck and into a monsoon ditch running alongside the road. Mistake. Argylls were above the drain, in defilade. Rapid firing along the length of the ditch, the Highlanders tumbled the North Koreans down, dead.

The driver attempted to accelerate out of the fusillade. As his perforated vehicle juddered forward, a member of Yetman’s platoon scurried alongside in the monsoon ditch and hurled a grenade. It detonated on the truck bed. Brewing up, the vehicle careened to the side of the street, its occupants dead. Sudden silence. The contact had been, Yetman thought, ‘a bit dodgy’. Remarkably, given the extreme close range – no more than the width of a street – no Argyll had been hit. Thirty North Koreans – including a group of prisoners taken earlier and mown down in the crossfire – sprawled on the road.6 There were no wounded to be tended, no captured to be interrogated. ‘When you are firing at a range of 20 feet and you get an angry Jock – well, he shoots to kill,’ said the battalion adjutant, Captain John Slim. Flames flickering up from the burning truck lit the ruined street. Daylight was fading.

Orders arrived from Brigade HQ: Neilson was to consolidate his battalion and establish blocking positions west of Sariwon. By radio, Neilson summoned C Company, clearing the north of the town, back to the south. Then with his battalion second-in-command, Major John Sloane, he drove out of the town down the southwest road in a land rover and a tracked carrier to recce the blocking position. A CO and second-in-command should not be together; it was a rare mistake by Neilson.

The clock ticked. The party did not return. The radio was silent. ‘This was quite fun!’ thought Intelligence Officer Sandy Boswell grimly: The battalion was leaderless in an unsecured town with night falling. Gordon-Ingram took command in Neilson’s absence.

It was now some time after 18:00. As evening gloom cloaked Sariwon’s arena of broken streets, perhaps the most extraordinary encounter of the Korean War was about to take place; an encounter that, were it fiction, would defy credibility.

C Company, along with the mortar platoon and a troop of American tanks, was returning south along the main road. With sporadic sniping echoing through the streets, the column was tactically deployed. Behind the turret of the leading Sherman, stood a green National Service officer: Second Lieutenant Alan Lauder, a Dunfermline native. Beside him, well-spaced Jocks of his platoon were pacing on either side of the crawling tank. The column entered the illumination of a stationary truck’s headlights. Abandoned. A Jock broke ranks and smashed the lights with his rifle butt. Then, from his vantage point at the head of the column, Lauder made out ‘a horde of people’ advancing up the street towards him. He could see that they were armed and accompanied by stacked ox carts. As the two columns converged, the newcomers – now recognisable as Asian troops – politely dragged their carts to the side of the road to let the Argylls pass. ‘They were giving us a friendly reception, waving and rubbing shoulders with our guys,’ Lauder recalled. Obviously, the men were South Korean allies. But as the Sherman trundled by, the American tank commander’s head popped out of his turret and scrutinised the strangers. ‘They’re goddamned Gooks!’ he hissed.

For the first time in his life, the Scotsman experienced something he had only read about: A crawling sensation on the back of his neck as hairs bristled up in a primeval response to fear: ‘Gook’ was the slang GIs used for enemy. ‘What am I gonna do?’ asked the tank commander. ‘For God’s sake keep motoring,’ Lauder retorted. ‘I’m not going to start a fight here!’ The American disappeared inside his armoured shell, clanging his top hatch closed. Ahead was a junction. The enemy column seemed endless. Seeing the opportunity to escape, Lauder led his column off the main road, down a side street. The nerve-wracking drive, Lauder estimated, had taken 10 minutes; somehow, the Argylls had got away with it. Then, from behind, a shot rang out.

The rear of Lauder’s column consisted of a couple of US tanks and the Argyll Mortar Platoon, mounted in seven Bren gun carriers: low, open boxes of armour on caterpillar tracks. Some mortar men were in the carriers; others pacing alongside, shepherding half a dozen POWs captured north of the town. At the rear of the platoon was a Glasgow-born private, Henry ‘Chick’ Cochrane. The column halted. Cochrane saw why: A crowd of Korean troops was approaching. The soldiers and the idling armoured vehicles in the town square reminded Cochrane fleetingly of Colchester. ‘I said, “South Koreans – how the hell did they get here?”’ He called one over. The man walked across, smiling. As he approached, Cochrane felt a lurching shock: There was a red star in the man’s cap. ‘I said, “Enemy troops! We are not gonna see daylight tomorrow!”’ Circumspectly, Cochrane approached his platoon commander, Captain Robin Fairrie. Echoing the American tanker’s enquiry to Lauder, he whispered urgently, ‘What are ye gonna do?’ Fairrie, a heavyweight boxer popular with the Jocks for his boyish sense of mischief, was nonplussed: ‘You tell me!’ he replied. This delicate scenario was not covered at Sandhurst.

The mingling North Koreans seemed delighted, pointing excitedly at the white stars stencilled on the hulls of the fighting vehicles (UN air recognition signals). Grins flashed, mutually incomprehensible greetings were exchanged, cigarettes and souvenirs passed back and forth. Passing enemy clapped Jocks on the back, murmuring, ‘Russki!’ The penny dropped: As the Argylls were returning from the north of Sariwon to the south, the enemy, entering the town from a separate road, had mistaken them for Russian allies joining the war. The Argylls’ kit reinforced the North Koreans’ belief, for the Jocks were wearing knitted cap comforters – similar to Red Army headgear of the Second World War – and carrying British, not American, small arms.*

Another mortar man, Adam MacKenzie, was walking beside a carrier; Fairrie had somehow passed word to his men that they were not to speak, only nod, and to keep the prisoners moving. The POWs seem not to have realised what was going on – or were too frightened to take advantage. ‘Let’s get out of here!’ MacKenzie fretted. But fraternisation continued: A North Korean officer approached Fairrie. ‘Russki?’ he enquired. Fairrie replied with the only Russian he knew: ‘Tovarisch!’7 This was enough to secure a special favour: A uniformed North Korean female joined him on his jeep, motioning playfully for the speechless officer to pass her his balmoral.8

Tension wound tighter; this impossible, ludicrous situation could not last. Inside carriers, Jocks quietly pulled the cocking levers of Bren guns and loosened hand grenade pins. ‘There was going to be a big skirmish in a minute,’ said Cochrane. ‘Ye could hear it: The calm before the storm!’ As the head of the column, led by Lauder, was trundling down the junction, one of the American tank commanders at the rear got into an altercation with a North Korean. The sergeant reached down from his turret, grabbed a Korean’s rifle by the barrel, and tried to yank it away. The Korean squeezed the trigger. The GI slumped, gut-shot. ‘We’d been rumbled!’ MacKenzie realised. Almost immediately, the second US tank opened up with machine guns. The convivial scene disintegrated into pandemonium.

MacKenzie hit the deck – North Koreans were frantically setting up machine guns – then vaulted into a carrier. Cochrane did the same. Jocks were emptying Brens and Stens and hurling hand grenades over the sides of the armour, while staying as low as possible. In the confusion, the prisoners disappeared, while astounded enem...