- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

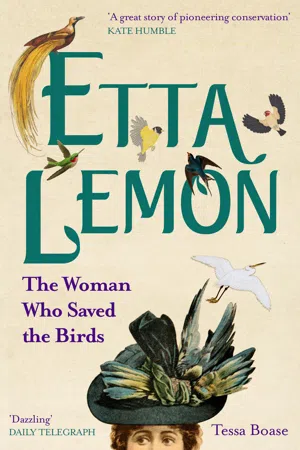

Read the fascinating story of one of the greatest unsung figures of the nature conservation movement, founder of the RSPB and icon of early animal rights activism, Etta Lemon.

A heroine for our times, Etta Lemon campaigned for fifty years against the worldwide slaughter of birds for extravagantly feathered hats. Her legacy is the RSPB, grown from an all-female pressure group of 1889 with the splendidly simple pledge: Wear No Feathers.

Etta’s long battle against ‘murderous millinery’ triumphed with the Plumage Act of 1921 – but her legacy has been eclipsed by the more glamorous campaign for the vote, led by the elegantly plumed Emmeline Pankhurst.

This gripping narrative explores two formidable heroines and their rival, overlapping campaigns. Moving from the feather workers’ slums to high society, from the first female political rally to the rise of the eco-feminist, it restores Etta Lemon to her rightful place in history – the extraordinary woman who saved the birds.

ETTA LEMON was originally published in hardback in 2018 under the title of MRS PANKHURST'S PURPLE FEATHER.

'A great story of pioneering conservation.'

KATE HUMBLE

‘Quite brilliant. Meticulous and perceptive. A triumph of a book.’

CHARLIE ELDER

‘Shocking and entertaining. The surprising story of the campaigning women who changed Britain.”

VIRGINIA NICHOLSON

‘A fascinating and moving story, vividly told.’

JOHN CAREY

‘A fascinating clash of two causes: rights for women and rights for birds to fly free not adorn suffragettes’ hats. An illuminating story, provocative, well-researched and brilliantly told.’

DIANA SOUHAMI

A heroine for our times, Etta Lemon campaigned for fifty years against the worldwide slaughter of birds for extravagantly feathered hats. Her legacy is the RSPB, grown from an all-female pressure group of 1889 with the splendidly simple pledge: Wear No Feathers.

Etta’s long battle against ‘murderous millinery’ triumphed with the Plumage Act of 1921 – but her legacy has been eclipsed by the more glamorous campaign for the vote, led by the elegantly plumed Emmeline Pankhurst.

This gripping narrative explores two formidable heroines and their rival, overlapping campaigns. Moving from the feather workers’ slums to high society, from the first female political rally to the rise of the eco-feminist, it restores Etta Lemon to her rightful place in history – the extraordinary woman who saved the birds.

ETTA LEMON was originally published in hardback in 2018 under the title of MRS PANKHURST'S PURPLE FEATHER.

'A great story of pioneering conservation.'

KATE HUMBLE

‘Quite brilliant. Meticulous and perceptive. A triumph of a book.’

CHARLIE ELDER

‘Shocking and entertaining. The surprising story of the campaigning women who changed Britain.”

VIRGINIA NICHOLSON

‘A fascinating and moving story, vividly told.’

JOHN CAREY

‘A fascinating clash of two causes: rights for women and rights for birds to fly free not adorn suffragettes’ hats. An illuminating story, provocative, well-researched and brilliantly told.’

DIANA SOUHAMI

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Etta Lemon by Tessa Boase in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Storia & Biografie in ambito storico. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part 1

Feathers

1

Alice Battershall

1885

On a September morning in 1885, a young woman and her mother stood in the Guildhall dock, close by St Paul’s Cathedral. Alice Battershall, 23, was charged with stealing two ostrich feathers. She had concealed them about her body while working for Abraham Botibol, a prominent feather manufacturer operating from Carthusian Street, an alley just off Aldersgate Street in the City of London. The women were propelled into the ornate Justice Room by Police Constable Wackett, a 27-year-old former butcher, specialist in larceny and plain-clothes investigator. Wackett had reason, today, to feel satisfied.

It was a busy morning at the Guildhall – the busiest for some weeks. Ostler’s horses waited patiently in the square outside, shadowed by St Lawrence Jewry. The late morning sun fell in a needling beam straight up King Street, touching the Guildhall’s grand gothic entrance. Inside, a stream of petty criminals came, one by one, before Alderman Phineas Cowan. Their offences ranged from ‘indecent pictures on matchboxes’ to ‘bad meat’; from a five-year-old boy found begging, to cruelty to horses. Few women came before him. Fines of ten or five shillings were the normal punishment.

The theft of ostrich feathers was a more interesting case. The ears of the Morning Post’s reporter pricked up as Mr Cowan asked some searching questions. Alice Battershall confessed that she had been ‘put up to the theft’ by her mother, Emma Battershall, 44, who in turn had passed the items on to wardrobe dealer Sarah Greenhalgh, who lived just ten doors away in Finsbury. To Mr Botibol, the feathers were worth seven shillings apiece; but Mrs Greenhalgh knew desperation when she saw it, and her fixed price for Mrs Battershall was one shilling per plume. She had, she said, bought three ostrich feathers off Emma Battershall during the past fortnight, and probably 20 more off her ‘at various times’. PC Wackett had, it appeared, stumbled upon a female fencing ring.

This was not the first time such a case had come before the Court of Common Council, the City of London’s adjudication system for petty crime. Mr Botibol was a regular in the Guildhall Justice Room. He had, he pointed out, lost ‘a large number’ of plumes recently. Yet he was also known in the courts as a hard-nosed man of commerce – a London-born, middle-aged Sephardi Jew with heavy interests in the trade and prone to exploit his largely female workforce.

On this September morning, Alderman Cowan weighed the evidence, taking into account Alice Battershall’s punitively low and irregular wages of five shillings a week, and the fact that the sudden ‘feather slump’ of 1885 had further squeezed her earnings. Fashion was a fickle creature, and despite promises of ‘Constant Employment for Ostrich and Fancy Feather Hands (Good)’, Botibol’s workers were laid on and off as required, making this a highly precarious living. But a crime was a crime. The magistrate pronounced that since the elder woman had ‘led her daughter into this matter’, she would be sentenced to six weeks’ hard labour in prison. Alice was condemned to three weeks. This was an unusually harsh sentence by Guildhall standards, where punishment by hard labour typically amounted to three days. One might even suspect Botibol and Cowan of a conspiracy.

Alice Battershall was a feather washer – an unsavoury, unskilled job, and a lowly link in a now vanished trade. If you look under the letter ‘F’ in the Post Office Directory for 1885 you will find them, clustered around the City and the East End in a litany of occupations entirely lost to us today. There, among the flageolet makers, flannel factors and flag makers, the fender and fire iron makers, fibre dressers and fire bucket makers, are the highly specialised artisans of the feather trade. Here are Alice and her cohorts – feather washers, purifiers, dyers, beaters, curlers, willowers and shapers. Mrs Pankhurst’s plume would have passed through every one of these stages before it reached the milliner’s shop. This was a commodity with its own language and hierarchies; its gradations of skilled and unskilled, men’s and women’s work, particular health hazards, rates of pay, slack seasons and a known network of mostly Jewish employers between which the workers passed, were dropped and picked up again. Plumage was a legitimate Victorian trade, just like the fur, leather or taxidermy trade. It was an all-encompassing world.

Two thousand ‘feather hands’ were employed by London’s plumage industry in the 1880s; thousands more worked in the plumassiers of Paris and the ‘feather foundries’ of New York. Alice’s fingers picked over and prepared feathers that would end up on the heads of princesses and courtesans, of suffragists and debutantes, music-hall singers and parlourmaids. She was invisible then and she’s invisible today. We don’t have an image – just a two-inch newspaper cutting on her crime, headlined ‘Police Intelligence’. Yet we can imagine her standing there in the Guildhall dock, in a squashed straw bonnet with a defiant straggle of plumage, her skirts long and full, her corset tight and her grubby bodice buttoned high at the neck.

Alice’s symbolic role, in this tale, is to stand in for all the ‘feather hands’ employed by men like Botibol in London’s lucrative plumage trade. Alice can be found washing and curling ostrich plumes in every census return – from her teens, right up to her death, in 1921. By then, her daughter, Louisa, was working in the trade alongside her.

Alice Battershall represents the hidden link between the plumage hunter and the millinery counter. She links the impoverished slums of the East End with the high glamour of courtly circles. She is not, nor ever likely to be, politically active – she is just getting by – but Alice and her exploited co-workers are a spur to those women who fought for the vote and for equal rights. She stands to gain in this story arc.

Yet she also stands to lose. The industry Alice depends on to stay afloat is the focus for Mrs Lemon’s imminent bird protection agitation. She is a mute symbol of the vilified, ‘repulsive’ plumage trade. If Mrs Lemon wins her battle to halt the millinery juggernaut and ban the importation of feathers, Alice Battershall, and those like her, stand to lose everything.

The theft of a feather seems, today, an absurdly petty crime. But behind that swift, stealthy and almost erotic action of Alice Battershall’s – her fingers pushing the plumes softly up each leg-of-mutton sleeve of her tightly buttoned jacket – lay a complex value system, the meaning of which is now entirely lost to us. These were not just feathers to the Battershall women, nor to manufacturer Mr Botibol.

Most obviously, they represented hard cash – instant cash, in the case of Alice and her mother. Botibol dealt in more abstract realities. He wasn’t attached to the two feathers per se – it was what they represented that mattered. These ostrich feathers had come into his apprentice’s hands via a highly sophisticated mercantile web serving a global fashion industry. Each stolen feather had its own intricate backstory of hunter or ostrich farmer; Jewish agents in sun-baked ports of the British Empire; bare-backed stevedores loading and unloading the holds of cargo ships with names like Bookhara, Arab and Trojan, ships which ended their long journeys at the Victoria and Albert Docks in East London. In 1885, Britain’s imperial capital was the world’s modern feather bourse. Monthly, Abraham Botibol walked a curving route to the Cutler Street and Billiter Street feather warehouses from his premises off Aldersgate Street. Nobody outside the trade was allowed in these many-floored brick buildings. Identity was checked at the door; warehouse attendants shadowed each visitor. This was a masculine environment with a highly sensual, luxury booty. Each floor, each high-ceilinged room contained unimaginable quantities of quills, exotic bird skins and plumes, laid out in their raw state for inspection. At busy times, it was said that dealers ‘nearly suffocated under their wares’. The millinery trade moved from ‘fancy feathers’ (the plumage of wild birds) to ostrich plumes, to artificial flowers and back again, as the fashions and seasons changed.

Botibol dealt mostly in ostrich plumes: for court, ladies’ fans, funerals, hats and the stage. There were plumes for every tier and wallet of society – from the most luxurious, full-bodied ‘White Prime’, to a diminutive ostrich ‘tip’. Every woman aspired to own one. Whatever your outlay, a plume would retain its value as an investment, as well as an adornment, kept wrapped in tissue in a box, cleaned and re-curled once a year, then passed down to your daughter. Working girls saved up and clubbed together for a plume, taking it in turns to wear it on their best hat.

In the early years of the trade, each feather had come from a wild bird, hunted down and killed in the Sahara Desert. But since ‘the Eclipse’ egg incubator had been patented in 1864, ostrich farming in the arid Western Cape of southernmost Africa had taken off. Birds could now be raised in their hundreds and clipped or plucked every eight or so months, flooding the western market with so many plumes that it was hard to imagine there were enough heads left among women to wear them.

The Billiter Street feather warehouse was stacked with luxurious, soft bundles, freshly unpacked from their wooden cases and tissue paper wrappings. The preserving naphthalene crystals had been shaken out; the plumes measured, weighed and laid out in ‘lines’ according to quality and provenance, each lot separated by chalked wooden boards. There were 14 varieties of ostrich plume on sale, and countless grades within them depending on where from the bird they had been clipped – Whites (the most luxurious), were followed by Feminas, Byocks, Spadones, Boos, Blacks, Drabs and Floss. They ranged in colour from creamy white to jet-black; from the full-blown and palmy to the stunted and bedraggled. Buyers had two days in which to inspect stock before a sale. Carefully, Abraham Botibol would pick up each feather by its stalky quill and balance it in his hands. One needed, so they said in the trade, an ‘ineffable feel for feathers’. What profit could be turned on each bundle? What were the cost margins? What might he stand to gain? Or – if the whimsical fashion market changed its mind – what might he lose?

As demand for ‘plumiferous’ fashion accessories soared from the 1870s onwards, importers, brokers, auctioneers, wholesalers and feather handlers grew by the hundred. Most were concentrated around one tight area in the City of London, bordered by Aldersgate, London Wall, Bishopsgate and Old Street. Auctions had increased from quarterly to bimonthly and now were held monthly (soon to become fortnightly). Botibol attended them all. He was buying for both British and the foreign markets. Some 80 per cent of what he routinely bid for would be exported ‘in the rough’ to Paris, Vienna, Berlin and New York, where it would be processed by female labour into the fancy decorations required by milliners on both sides of the Atlantic.

And so Alice Battershall’s two feathers came under the hammer, a trivial part of a highly critical whole – a luxury commodity shipped in tonnes, packed in cases, bid for in bundles and weighed in pounds. Once delivered in crates by horse and wagon, the feathers would then be shuttled through a cascade of treatments by Abraham Botibol’s workhands. They would be strung, dyed, washed, dyed again, dried, thrashed, trimmed, finished, parried, willowed, fashioned and curled. He might sell a single item to a millinery wholesale warehouse for seven shillings, or direct to a customer for 30 shillings. Once affixed to a ladies’ hat by a milliner and displayed in a Bond Street shop window, its value could be anything up to £5 (£500 in today’s money). On the black market, though, as those plumes passed from the Battershall women to wardrobe dealer Sarah Greenhalgh, their value was just one shilling.

Baldly, feathers represented cash.

2

Inspector Lakeman

1887

One shilling was actually a good return for a plume on the black market. A trawl through the newspapers of the 1880s reveals that the warren of courts and alleys between Clerkenwell and Whitechapel were thick with stolen feathers. Stuffed behind lockers, down corsets, under attic floors – feathers were secreted here and there in a nefarious trade operating brazenly alongside the manufacturers.

In 1886, Abraham Botibol was back in the courts again in pursuit of another worker, 49-year-old Mary Anne Baker. The woman was accused of having stolen five shillings-worth of ostrich feathers, subsequently discovered in her lodgings. She argued that she’d been given them in lieu of pay, which wasn’t such an implausible defence since the industry was in one of its periodic slumps. During a downturn it was easier to pay workers with feathers rather than with hard cash. But Mary Anne Baker wasn’t believed. She was sentenced to 21 days’ hard labour: the same punishment as Alice Battershall. She had stolen to stay afloat.

There were no unions for those working in the feather trade. This was a below-the-radar world, almost invisible to the public eye, its nimble-fingered female workers acutely vulnerable to exploitation. Not quite invisible, though. The Victorian government’s Factory and Workshop Inspectors were remarkably thorough, writing detailed, surprisingly nuanced reports. Inspectors Mr Lakeman, Major Beadon, Mr Blenkinsopp, Mr Knyvett and Mr Henderson combed the streets of industrial Britain, making spot visits to working premises. They were looking for employer abuses.

Since the Factory and Workshop Act had been updated in 1878 to include all trades, the working day had, in theory, improved for Britain’s workforce. These inspectors were searching for evidence of overcrowding, poor ventilation, inadequate safety and, in particular, overworking. The Act now stated that women were to work no more than 56 hours a week – a rule that had backfired, as it prompted women to take extra home for piecework wages. This meant you were paid by the piece, be it stitched buttonholes, boned corsets or curled ostrich feathers.

Mr Lakeman’s responsibility was for the small workshops of the Central Metropolitan District, London. Unlike the textile factories of the industrial north, this was a shadowy, impenetrable world. These were rooms over stables, attics up decrepit stairs, back chambers containing dozens of slop-work tailors, umbrella pointers, glove makers and shoe heelers. Mr Lakeman despaired for central London’s exploited workforce: ‘poor people . . . hard working, struggling to maintain themselves and passively submitting to the exigencies of a hard lot.’

With his naphtha lamp, he walked the alleys, the courts and cul-de-sacs, combing ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Contents

- Prologue

- Part 1 – Feathers

- Part 2 – Birds

- Part 3 – Hats

- Part 4 – Votes

- Part 5 – Power

- Epilogue

- Notes

- Select Bibliography

- Acknowledgements

- Index

- Picture Credits

- Dedication

- About the Author

- Copyright