![]()

PART I

Evil Town

![]()

Chapter 1

Mean Streets

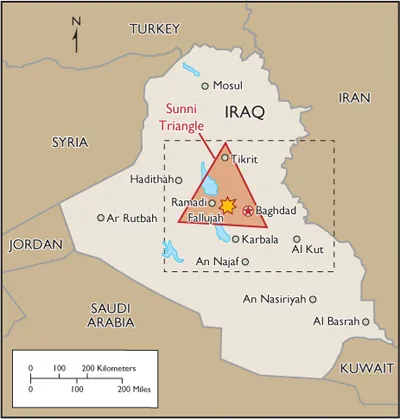

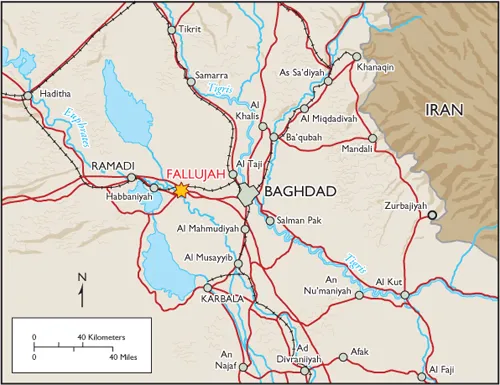

Fallujah is located approximately forty-three miles northwest of Baghdad, just east of Ramadi, the provincial capital of al-Anbar, the largest of Iraq’s eighteen provinces. Al-Anbar borders Jordan and Syria in the west and Saudi Arabia in the south. Most of its inhabitants are Sunni Muslim from the Dulaim tribe, a very strong, traditionally powerful clan with an obstreperous reputation. Fallujah itself is situated on the east bank of the fertile Euphrates River, on the ancient crossroads of the Silk Road, Iraq’s oldest and most important commercial artery. The Silk Road, current day Highway 10, connects Saudi Arabia with Syria and Turkey, and Baghdad with Amman, Jordan. The city’s location made it a hub for commerce and trade, both legal and illegal—a way station for merchants, smugglers, and thieves crossing the desert. For centuries, heavily laden caravans passed through Fallujah’s dusty streets, stopping only long enough to replenish supplies and bargain with its flinty-eyed citizens. Highway robbery was a tradition that went back hundreds of years. Even in recent years, according to New York Times reporter Anne Barnard, “Drivers who drove from Jordan into Baghdad would always … drive quickly through Fallujah or drive through very early in the morning so you don’t get stuck up on the roads.”

The city is within the so-called “Sunni Triangle,” a swath of densely populated territory north of Baghdad where the majority of its inhabitants are Sunni Arabs. Roughly triangular in shape, the Sunni Triangle encompasses the major cities of Baghdad, Fallujah, Ramadi, Samara, and Tikrit, Saddam Hussein’s birthplace. Ramadi anchors the west base line, with Baghdad on the east and Tikrit in the north. Each side measures approximately 125 miles long. “The Sunni Triangle is made up of large clans,” an Iraqi explained. “Everybody in a clan knows everybody else. I only trust the people I know very well. If someone comes from another tribe, I don’t trust him until I get to know him.” For hundreds of years, this close-knit tribal structure enabled the people to survive the many invasions and rivalries between cultures. “This area has been occupied since 579 B.C.,” U.S. Army Lt. Col. Alan King explained. “The tribal system was an important part of their survival. The tribes came up with a tribal law to be able to work among each other.”

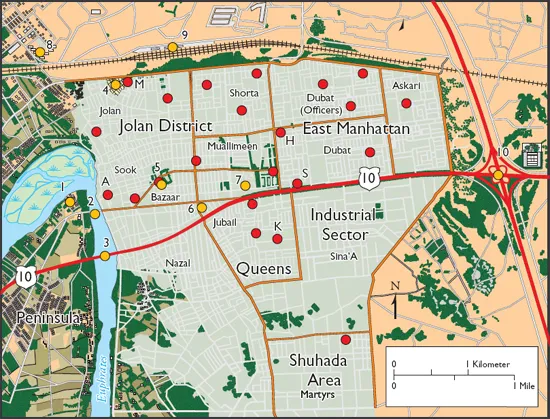

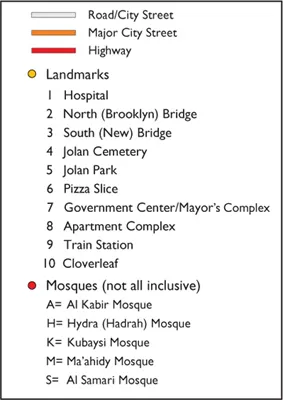

Fallujah Key Terrain

In 1947, Fallujah’s population was 10,000. With the influx of oil revenue, the development of industry, and its location on Highway 10, Fallujah grew rapidly. By 2003, its population was estimated to be between 250,000 to 350,000, equivalent to the size of Raleigh, North Carolina. Marine Maj. Christeon Griffin described the city’s size as “maybe four kilometers wide and three kilometers deep from north to south, twenty square kilometers total. It nested right up against the Euphrates River on its western boundary, and everything to the north, south, and east is just wide open desert.” Griffin thought that “because of the city’s proximity to the Euphrates that periodically flooded and with the rotting trash all along the streets, Fallujah basically stinks.” Major Stephen Winslow echoed Griffin’s sentiments: “I couldn’t wait to get away from the smell. The place just stunk!”

Fallujah contains more than fifty thousand densely packed buildings laid out in two thousand city blocks, averaging one hundred by two hundred meters on a side. “Most of them are square residential buildings,” according to Griffin, “so close together that there’s only a two-foot gap between them … literally your house is touching your neighbors’ house … minimal wasted space. It is the most densely built-up place I’ve ever seen.” The streets are narrow and lined with “concrete walls, maybe six, eight feet high running around the perimeter of every dwelling, which made it pretty difficult to maneuver a vehicle through there,” Griffin recounted. One observer noted that, “As in many cities in Iraq at the time, half-completed homes, heaps of garbage, and wrecks of old cars graced every neighborhood.”

Fallujah, by all accounts, was “meaner than a junkyard dog” and hostile to all foreigners, meaning anyone not from the city. Fallujah has always been sort of an untamed city, even in the minds of other Iraqis. Bing West characterized its people as “strange, sullen, wild-eyed, badass, just plain mean,” who owed their loyalty to a tribe or subtribe led by a sheikh. These powerful men were the dominant force in the inner life of the tribe and its relations with the nontribal world and the authorities. Because relationships are central to tribal life, Saddam Hussein heavily recruited members of these clans and tribesmen into his elite Republican Guard and the Iraqi Intelligence Service (IIS) and provided them privileges to ensure at least some loyalty to his regime. In addition, Hussein gave his handpicked tribal sheiks money and weaponry and even turned a blind eye to their smuggling activities. However, to hedge his bet, he stationed elements of his army in the large cluster of military bases outside the city.

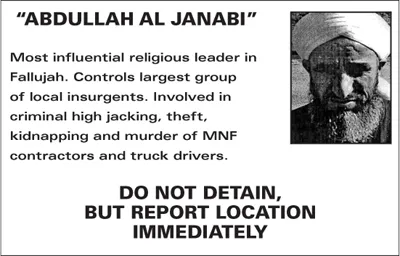

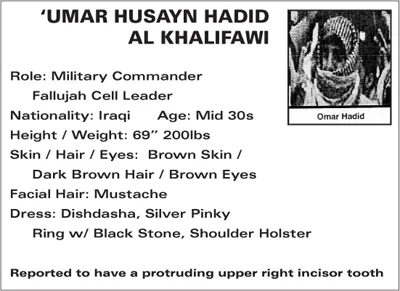

Mike Tucker, in Among Warriors in Iraq: True Grit, Special Ops, and Raiding in Mosul and Fallujah, wrote, “Fallujah has been the base for smugglers who trade in illicit goods of all size, kind, and make, from Syria and Jordan to Iran on the west-to-east route, and from Saudi Arabia to Turkey on the north-south route.” It is a place where the sheiks and imams take their cut of the illegal trade and viewed the coalition force as a threat to their continued prosperity. One of the most powerful imams in Fallujah after the fall of Hussein was the firebrand Sheik Abdullah al-Janabi, an anti-coalition cleric who preached holy war against the Americans. Another powerful leader in the insurgent movement, Omar Hadid, headed the local branch of Jordanian-born militant Abu Musab al-Zarqawi’s organization. Hadid, a former electrician, was a brutal, ruthless killer who organized an anti-coalition unit called the Black Banners Brigade, composed mostly of Syrian fighters.

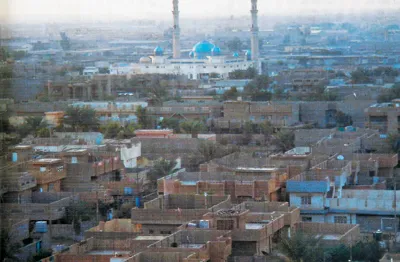

During the battle of Fallujah, the insurgents used many of its minarets for sniper and observation positions. Over 60 percent of them contained weapons, explosives, and ammunition, in violation of the Law of War. Defenseimagery.mil 04120-M-0036Y-013

Lieutenant Colonel Michael Eisenstadt, U.S. Army Reserve, wrote that “tribesmen are intensely jealous of their honor and status vis-à-vis others, to the extent that honor has been described as the ‘tribal center of gravity.’” Retaliation for real or perceived slights is a fundamental aspect of the tribal honor-based system. Sadoun al-Dulame, a Baghdad-based political scientist, said, “This is a revenge culture where insults to people’s honor will always be repaid with violence,” and once started are almost impossible to stop. Amatzia Baram, an Iraq expert at the U.S. Institute for Peace, explained that “it’s gone beyond ‘you killed my cousin so I have to kill you.’ It’s about religion.” They learned that Americans have different values, and this makes killing an American less dangerous than killing someone from another tribe. “If I kill someone from your tribe, I know another member of my tribe will definitely be killed,” Baram wrote, “but people of Fallujah have learned that when they kill Americans nothing much happens.”

Fallujahans practice extreme Wahhabism, a radical religious philosophy that preaches nontolerance of infidels (anyone not Wahhabi), jihad against coalition forces, and martyrdom in the name of these goals. Wahhabism gained strength among the Sunni after Hussein’s fall. “We lost our positions, our status,” a Sunni leader grumbled. “We were on top of the system, now we are losers.” The city’s imams preached takfir, characterizing the Shia as infidels. Foreign terrorists such as Zarqawi exploited this schism between the two sects in an attempt to drive them into open civil war, placing the United States in an untenable position.

This conservatism contributed to the city’s aversion to secular authority, particularly the occupation of foreign troops. Jeffrey Gettleman described it as “a traditional place, where many restaurants have their own prayer rooms or mini-mosques tucked away in the back.” The faithful are proud that Fallujah is known as the “City of Mosques,” because of its one hundred green-domed places of worship. Griffin recalled, “There seems to be a mosque on every city block, so you’ve got minarets all over the place. At night, even though we cut off power to the city, the minarets’ green lights stayed on, and they were still able to broadcast audio messages. It added to the eerie effect of the city.”

![]()

Chapter 2

Bloody Encounters

There was something evil in that town.

—Col. Arnold Bray, 82nd Airborne Division

In the initial invasion of Iraq, U.S. forces generally bypassed Fallujah in their drive to capture Baghdad. A senior Army officer admitted, “This part of the Sunni Triangle was never assessed properly in the plan.” The first Americans to enter the city were CIA agents, special forces, and a company of the 1st Armored Division. They could not find anyone to assist them, despite the city’s leaders’ complaining they needed help in ridding Fallujah of bad elements. Captain John Prior wrote tongue-in-cheek, “The Iraqis are an interesting people. None of them have weapons, none of them know where weapons are, all the bad people have left Fallujah, and they only want life to be normal again. Unfortunately, our compound was hit by RPG fire today, so I am not inclined to believe them.” The Americans quickly moved on and were replaced by several different units. An army intelligence officer said, “Fallujah had five different units handling it between April ’03 and April ’04. This is exactly the wrong way to prosecute a counterinsurgency fight.”

It wasn’t until late April 2003 that the 1st Battalion, 325th Airborne Infantry Regiment, entered the city. “We came in to show presence just so the average citizen would feel safe,” Col. Arnold Bray explained. The paratroopers were greeted by stony silence as they set up camp in the former headquarters of the Baath Party on the main street in the center of the city. A few hundred yards south of the main road, Charlie Company’s 150 soldiers occupied the two-story al-Qa’id Primary School, an easily defended structure that had a seven-foot-high perimeter wall around the compound and excellent observation from the roof. “The only reason we occupied the school was to find a location where we could communicate with the people,” the battalion commander reported.

Iraqi protesters carry signs, one of which reads in English, “We demand the American forces to release our sister who take from 20 street.” Insurgents would sometimes use the demonstrations to provoke American forces. U.S. Army

For several days, there was an uneasy standoff as American motorized patrols drove through the streets in a show of force. However, on the evening of April 28, Saddam Hussein’s birthday, a raucous crowd of about 250 residents marched on the school to protest the American presence. According to the soldiers, they came under attack from gunmen in the crowd: “The bullets started coming at us, shooting over our heads, breaking windows,” and they returned fire. A local Moslem cleric countered, “It was a peaceful demonstration. They did not have any weapons.” Charge brought countercharge, but the death count seemed to support the Iraqis. Fifteen residents were killed and several dozen wounded, including women and children. There were no American casualties. Al Jazeera quickly reported that the soldiers were unprovoked and shot indiscriminately. The Arab media quickly followed up with a drumbeat of other anti-American stories.

The shooting inflamed the Sunni population, many of whom traced the beginning of the resistance to the incident. “The resistance started that day [April 29],” according to Saad Ala al-Rawi. “Fallujah was the first city that resisted the occupation.” Al Jazeera broadcast video of hundreds of mourners marching through the streets, carrying coffins and chanting, “Our soul and blood we will sacrifice.” A close-up shot framed one man crying, “They are slaughtering our people. Now all the preachers … and all youths are organizing martyr operations against the American occupiers.” Fallujah quickly became a mecca for anti-American insurgents. One insurgent bragged, “People join us from all walks of life. Those who cannot fight support us financially.”

The Iraq insurgency, according to a RAND report, “[was] diverse and widespread, and composed of groups of both nationalist and religious provenance [with] a desire to remove the U.S. and coalition presence from the country.” A Fallujah resident, Houssam Ali Ahmed, proudly announced, “The whole city supports this jihad” and “The people of Fallujah are fighting to defend their homes.” Sniper, random shootings, and improvised explosive device (IED) attacks increased, which coalition spokesmen claimed were instigated by foreign fighters. A captured insurgent, Abu Ja’far al-Iraqi, claimed that Jordanian arch-terrorist Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, known for beheading kidnapping victims, “was present during the fight, leading 100 men, and was in control of 5 percent to 10 percent of the territory.” However, most insurgent leaders insisted that the number of foreign fighters in the city was small, possibly 200 out of 1,200.

Lieutenant Colonel Clarke Lethin (center) was the tough, no-nonsense 1st Marine Division operations officer. A thorough professional, Lethin was a straight-off-the-shoulder officer who did not suffer fools well. 1st Marine Division

In May, Bremer’s CPA issued two orders: one disestablishing the Baath Party and the second one formally disbanding the Iraqi Army, which put thousands of men on the street, with no jobs, an uncertain future, and a simmering desire for revenge against the foreign interlopers. Abu Bashir, one of the most prominent sheiks in the region, agreed: “The biggest problem for the Americans is when they dissolved the army. Everybody immediately j...