eBook - ePub

The Daily Book of Classical Music

365 readings that teach, inspire & entertain

- 376 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Daily Book of Classical Music

365 readings that teach, inspire & entertain

About this book

Music lovers of all ages are drawn to the pure melodies of classical music. Now aficionados of this timeless genre can learn something about classical music every day of the year! Readers will find everything from brief biographies of their favorite composers to summaries of the most revered operas. Interesting facts about the world's most celebrated songs and discussions of classical music–meets–pop culture make this book as fun as it is informative. Ten categories of discussion rotate throughout the year: Classical Music Periods, Compositional Forms, Great Composers, Celebrated Works, Basic Instruments, Famous Operas, Music Theory, Venues of the World, Museums & Festivals, and Pop Culture Medley.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Daily Book of Classical Music by Leslie Chew,Scott Spiegelberg,Dwight DeReiter,Cathy Doheny,Colin Gilbert,Travers Huff,Susanna Loewy,Melissa Maples,Jeff McQuilkin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Classical Music. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

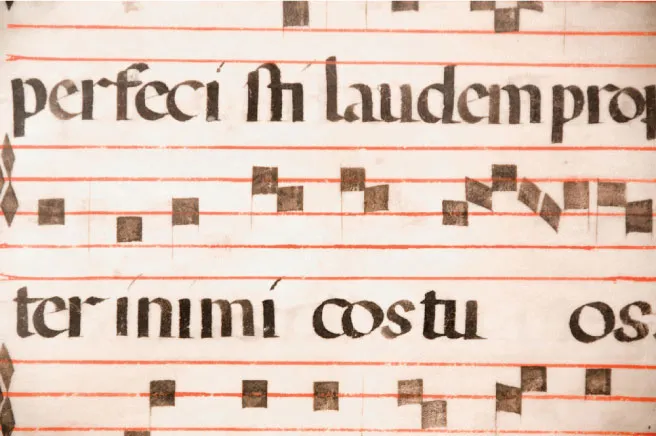

Medieval Music (400–1400)

WHERE IT ALL BEGAN

Medieval Music is music written in Europe in the Middle Ages—a time period that started with the fall of the Roman Empire and ended in the middle of the 15th century.

Because the creation of lasting manuscripts in the Middle Ages was quite an expensive endeavor (including the need for rare parchment and the use of scribes), there are very few surviving scores left from the Medieval time period, and the scores that do exist are from wealthy families and organizations—consequently not at all indicative of the common music of the day.

Medieval music, for example, can be classified into the sacred and the secular. However, since the majority of the studied scores are of the sacred variety, there isn’t much solid, accurate information about secular music.

Another hindrance of musicologists’ study of Medieval music is the rudimentary nature of the notation system of the times. Much of the music made was communicated through oral tradition, and when music was written, it certainly wasn’t with our exacting musical language. Instead, vague approximations of harmonic lines were outlined, and rhythms were merely suggested.

Unlike the notation, though, the instruments of Medieval music were strikingly similar to our modern versions. Both string and wooden wind instruments were used; pictures even suggest a comparable bow usage.

Medieval music is quite beautiful; it may sound a bit repetitive at times, but if you allow the plainsong chanting to wash over you, listening to it can be a wonderfully meditative experience. —SL

LISTENING HOMEWORK

Hildegard von Bingen’s Ordo Virtutum

Philippe de Vitry Motets

Guilliuame de Machaut Messe de Nostre Dame

Binary Form

WE KNOW WHAT WE WANT

Most musical forms result from two conflicting desires: the desire for something familiar, and the desire for something new. The binary form is the most basic example of this.

A simple binary form is in two parts—A and B—roughly equal in duration, and distinguished by different melodies. These parts are divided by clear cadences, and quite often each part is repeated, becoming a two-reprise form. Thus we end up with AABB, repeating A material to give us something familiar before moving to a new B section. The repetitions provide boundaries for the sections and give us the opportunity to hear and remember the melody.

Bach’s famous Air on the G String demonstrates how the B melody of the Air can be related to the A melody, with some similar rhythms and contours, but it also creates the feeling of something new by starting on a lower pitch and using different chords.

We like familiar things so much that a common variant of the binary form is the rounded binary form: ABA. The music is still in two sections, but the second section finishes with a return to the starting A melody, usually shortened. With the typical repeats, this becomes AA BABA. The theme from the third movement of Mozart’s Piano Sonata K. 284 shows how A can change when it returns. A modulates to a new key, but the return of A in the second section is altered to stay in the original key. —SS

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827)

THE MUSIC INSIDE HIS HEAD

Ludwig van Beethoven’s life and work straddled the classic and Romantic periods, and thus he is claimed by both. While many composers came from strongly musical families, Beethoven stood out from his kinfolk. There were musicians in his line—his father first taught him piano and violin—but none in his family before or since took any interest in composing.1 Nevertheless, from an early age Ludwig showed such genius that he was fancied to be the “new Mozart.”2

Taught by Haydn and Salieri in the classical style, Beethoven took a more emotional turn than his predecessors. Noticing (with panic) that his hearing was failing, Beethoven entered a period of fierce creativity, composing some of his most famous works. By 1818 he could no longer communicate except by writing; yet amazingly he continued to produce some of his most profound pieces while completely deaf—most notably his Symphony No. 9.

It is suggested that in his early years Beethoven wrote for his audience, but in his latter years—alone in his deafness—he apparently wrote for himself.3 His last pieces were so advanced and progressive that audiences of his day could not comprehend them. When Beethoven’s outer world fell silent, he could no longer draw influence from the music surrounding him. All that was left was the music inside his head. —JJM

Symphony No. 5 in C minor

BY LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN, 1808

In the entire history of music on planet Earth, there might not be any composition more renowned than the tour de force that is Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony. A commanding exhibition of power, majesty, accessibility, and sophistication, it towers as a testament to the magnificent possibilities of structured sound. Having said that, by no means is there universal consent that the work is even Beethoven’s finest accomplishment, but such is the subjective nature of musical interpretation, and such is the genius of Beethoven.

Of course, the symphony’s sinister da-da-da-DUM opening motif (which has been imaginatively compared to fate knocking on the door) has taken on a life of its own, but it functions as much more than a catchy hook. Not only in the frenzied first movement but throughout the entire symphony that authoritative rhythmic phrase makes a series of dramatic reappearances that serve to unify it. In the thrilling final movement, after 30 minutes of C minor turbulence, a long and satisfying sequence of C major chords brings a relieving sense of stability that the piece seems to frantically seek from the start. —CKG

RECOMMENDED RECORDING

Beethoven: Symphonies Nos. 5 & 7; Carlos Kleiber (conductor); Wiener Philharmoniker; Deutsche Grammophon; 1995

Dido and Aeneas

HENRY PURCELL (1659–1695)

“Remember me, but ah, forget my fate.” This haunting line from Dido’s lament, “When I Am Laid in Earth,” exemplifies for many listeners the exquisite example of Baroque opera that is Dido and Aeneas, the tragedy in three acts by English composer Henry Purcell that premiered in 1689. Librettist Nahum Tate loosely based the story on Virgil’s Aeneid, a love story involving Dido, Queen of Carthage, and Aeneas, who is shipwrecked at Carthage. When witches remind Aeneas that he is d...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- Day 1. Medieval Music (400–1400)

- Day 2. Binary Form

- Day 3. Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827)

- Day 4. Symphony No. 5 in C Minor

- Day 5. Dido and Aeneas

- Day 6. The Orchestra

- Day 7. Music Theory

- Day 8. Arena Di Verona

- Day 9. Mozarthaus Vienna

- Day 10. Beethoven and Rosemary’s Baby

- Day 11. Early Medieval (Before 1150)

- Day 12. Ternary

- Day 13. Johannes Brahms (1833–1897)

- Day 14. Eine Kleine Nachtmusik

- Day 15. Le Nozze di Figaro (The Marriage of Figaro)

- Day 16. The String Section

- Day 17. Ear Training and Sound Recognition

- Day 18. Carnegie Hall

- Day 19. The International Chopin Festival

- Day 20. Khachaturian’s Adagio in 2001: A Space Odyssey

- Day 21. High Medieval (1150–1300)

- Day 22. Inner Forms 1: Motive

- Day 23. Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy (1809–1847)

- Day 24. Air on the G String

- Day 25. Don Giovanni

- Day 26. The Violin

- Day 27. What is Musical Form?

- Day 28. Royal Albert Hall

- Day 29. Get in Line...Early

- Day 30. Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy” in Help

- Day 31. Late Medieval (1300–1400)

- Day 32. Minuet and Trio

- Day 33. Sergei Rachmaninov (1873–1943)

- Day 34. Adagio for Strings

- Day 35. Cosi Fan Tutte

- Day 36. The Viola

- Day 37. How we Perceive Musical Form

- Day 38. La Fenice

- Day 39. Moab Music Festival, Utah

- Day 40. Benjamin and the Man Who Knew Too Much

- Day 41. Renaissance (1400–1600)

- Day 42. Inner Forms 2: The Sentence

- Day 43. Richard Wagner (1813–1883)

- Day 44. The Four Seasons

- Day 45. Die Zauberflöte (The Magic Flute)

- Day 46. The Cello

- Day 47. Music as Organized Sound

- Day 48. Sydney Opera House

- Day 49. London Handel Festival

- Day 50. Gustav Mahler and Death in Venice

- Day 51. Renaissance—Notation (1400–1600)

- Day 52. Da Capo Aria

- Day 53. Arnold Schoenberg (1874–1951)

- Day 54. Clair de Lune

- Day 55. Il Barbiere di Siviglia (The Barber of Seville)

- Day 56. The Double Bass

- Day 57. Music Notation

- Day 58. The Metropolitan Opera House

- Day 59. Verbier Festival

- Day 60. Classical Music Television Broadcasts

- Day 61. Renaissance—Instruments (1400–1600)

- Day 62. Inner Forms 3: Subphrase and Phrase

- Day 63. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791)

- Day 64. Piano Concerto No. 2 in C Minor

- Day 65. La Cenerentola (Cinderella)

- Day 66. The Hurdy-Gurdy

- Day 67. Building Blocks

- Day 68. Massey Hall

- Day 69. Aspen Music Festival and School

- Day 70. Raging Bull and “Intermezzo” from Cavalleria Rusticana

- Day 71. Renaissance—Time Periods (1400–1600)

- Day 72. Suite

- Day 73. Claude Debussy (1862–1918)

- Day 74. Rhapsody in Blue

- Day 75. La Sonnambula (The Sleepwalker)

- Day 76. The Woodwind Section

- Day 77. Notation of Rhythm and Meter

- Day 78. Vienna State Opera House

- Day 79. Boston Early Music Festival

- Day 80. Strauss and 2001: A Space Odyssey

- Day 81. Baroque Music (1600–1750)

- Day 82. Theme and Variations

- Day 83. Frédéric Chopin (1810–1849)

- Day 84. Nocturne No. 2 in E Flat Major

- Day 85. Norma

- Day 86. The Flute

- Day 87. Tempo and Italian Terminology

- Day 88. Symphony Hall, Boston

- Day 89. Music Still Floats Through the Halls

- Day 90. Puccini’s “O Mio Babbino Caro” and A Room with a View

- Day 91. Early Baroque (1600–1650)

- Day 92. Inner Forms 4: The Period

- Day 93. Franz Liszt (1811–1886)

- Day 94. Canon in D major

- Day 95. L’elisir D’amore (The Elixir of Love)

- Day 96. The Clarinet

- Day 97. Melody

- Day 98. La Monnaie, Brussels

- Day 99. Newport Music Festival

- Day 100. All that Jazz—and Vivaldi Too

- Day 101. Middle Baroque (1650–1700)

- Day 102. Rondo

- Day 103. Hector Berlioz (1803–1869)

- Day 104. Three Gymnopédies

- Day 105. Lucia di Lammermoor

- Day 106. The Oboe

- Day 107. Harmony and Chords

- Day 108. Suntory Hall, Tokyo

- Day 109. Puccini Festival

- Day 110. The Planets are Everywhere

- Day 111. Late Baroque (1680–1750)

- Day 112. Concerto Grosso

- Day 113. Antonín Dvořák (1841–1904)

- Day 114. Symphony No. 9 (“From the New World”)

- Day 115. Rigoletto

- Day 116. The Bassoon

- Day 117. Intervals, Modes, and Emotions

- Day 118. Mariinsky Theatre

- Day 119. Glimmerglass Opera

- Day 120. Bach and the Silence of the Lambs

- Day 121. Classical Period (1750–1825)

- Day 122. Canon

- Day 123. Giuseppe Verdi (1813–1901)

- Day 124. Ave Maria

- Day 125. La Traviata (The Woman Who Strayed)

- Day 126. The Brass Section

- Day 127. The Minor Modes

- Day 128. Musikverein, Vienna

- Day 129. Festival D’aix en Provence

- Day 130. Pachelbel and Ordinary People

- Day 131. Rococo/Galant

- Day 132. Scherzo

- Day 133. Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750)

- Day 134. Symphony No. 94 (“Surprise”)

- Day 135. Aida

- Day 136. The Trumpet

- Day 137. Flats, Sharps, and Naturals

- Day 138. Place Des Arts, Montreal

- Day 139. Dresden Music Festival

- Day 140. Mozart in Out of Africa

- Day 141. Classicism: First Viennese School (1760–1775)

- Day 142. Sarabande

- Day 143. Aaron Copland (1900–1990)

- Day 144. Peter and the Wolf

- Day 145. Otello (Othello)

- Day 146. The French Horn

- Day 147. Gravity and Tonality in Music

- Day 148. Royal Opera House, London

- Day 149. Glyndebourne

- Day 150. Barber and Platoon

- Day 151. Classicism: First Viennese School (1775–1790)

- Day 152. Fugue

- Day 153. Charles Ives (1874–1954)

- Day 154. “Moonlight” Sonata

- Day 155. Der Fliegende Holländer (The Flying Dutchman)

- Day 156. The Trombone

- Day 157. Tonic Rules

- Day 158. Vigado, Budapest

- Day 159. Oregon Bach Festival

- Day 160. Bellini and the Bridges of Madison County

- Day 161. Classicism: First Viennese School (1790–1825)

- Day 162. Sonata

- Day 163. Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971)

- Day 164. Blue Danube

- Day 165. Lohengrin

- Day 166. The Tuba

- Day 167. Cadences

- Day 168. Royal Festival Hall, London

- Day 169. Rossini Opera Festival

- Day 170. Moon Music

- Day 171. Romanticism

- Day 172. Waltz

- Day 173. Béla Bartók (1881–1945)

- Day 174. Missa Papae Marcelli

- Day 175. Tristan und Isolde

- Day 176. The Percussion Section

- Day 177. Diatonic and Chromatic Scales

- Day 178. Festspielhaus, Bayreuth

- Day 179. Edinburgh International Festival

- Day 180. Mozart’s “Romance: Andante” and Alien

- Day 181. Sturm und Drang (Storm and Stress)

- Day 182. Concerto

- Day 183. Gustav Holst (1874–1934)

- Day 184. Peer Gynt

- Day 185. Faust

- Day 186. The Timpani

- Day 187. Key Relationships

- Day 188. Konzerthaus, Vienna

- Day 189. Banff Summer Arts Festival

- Day 190. Walt Disney’s Fantasia

- Day 191. Early Romanticism

- Day 192. Madrigal

- Day 193. Franz Schubert (1797–1828)

- Day 194. The Rite of Spring

- Day 195. Roméo et Juliette (Romeo and Juliet)

- Day 196. Tuned Percussion

- Day 197. Seventh Chords

- Day 198. Hungarian State Opera House

- Day 199. Beethovenfest Bonn

- Day 200. Ravel and 10

- Day 201. Late Romanticism

- Day 202. Ballad

- Day 203. Edvard Grieg (1843–1907)

- Day 204. Adagio for Strings and Organ in G Minor

- Day 205. Les Pêcheurs de perles (The Pearl Fishers)

- Day 206. Carillon

- Day 207. Monophonic Music

- Day 208. Theatre Des Champs-Elysees

- Day 209. Santa Fe Chamber Music Festival

- Day 210. Elgar and Elizabeth I

- Day 211. 20th-Century Music

- Day 212. Toccata

- Day 213. Nadia Boulanger (1887–1979)

- Day 214. Boléro

- Day 215. Carmen

- Day 216. The Glockenspiel

- Day 217. Polyphonic Music

- Day 218. Gewandhaus, Leipzig

- Day 219. Handel House Museum

- Day 220. Black & Decker® and Rimsky-Korsakov

- Day 221. Romantic Style

- Day 222. Passacaglia

- Day 223. Sergei Prokofiev (1891–1953)

- Day 224. Toccata and Fugue in D Minor

- Day 225. Samson et Dalila

- Day 226. Indefinite Pitched Percussion

- Day 227. Homophonic Music

- Day 228. Bolshoi Theatre

- Day 229. The Ottawa International Chamber Music Festival

- Day 230. British Airways and “Flower Duet”

- Day 231. Impressionism

- Day 232. Mazurka

- Day 233. Antonio Vivaldi (1678–1741)

- Day 234. Requiem

- Day 235. Les Contes d’Hoffmann

- Day 236. Indefinite Pitch Orchestral Drums

- Day 237. Implied Harmony

- Day 238. National Theatre, Munich

- Day 239. Ravinia Festival

- Day 240. Grieg and Nescafé®

- Day 241. Expressionism

- Day 242. Chamber Music

- Day 243. Richard Strauss (1864–1949)

- Day 244. The Nutcracker

- Day 245. Manon

- Day 246. The Piano

- Day 247. Contemporary Harmony and Polytonality

- Day 248. La Scala

- Day 249. The Stradivari Museum and the Ancient Instruments Collection

- Day 250. Prokofiev and Lexus

- Day 251. Futurism (1910–1930)

- Day 252. Symphony

- Day 253. Claudio Monteverdi (1567–1643)

- Day 254. Appalachian Spring

- Day 255. Boris Godunov

- Day 256. The Harpsichord

- Day 257. Suspended Fourths and Quartal Harmony

- Day 258. Concertgebouw

- Day 259. Salzburg Festival

- Day 260. Classical Music in a Sitcom

- Day 261. Second Viennese School

- Day 262. March

- Day 263. Dmitri Shostakovich (1906–1975)

- Day 264. A Midsummer Night’s Dream

- Day 265. Cavalleria Rusticana (Rustic Chivalry)

- Day 266. The Clavichord

- Day 267. Sounds Like Change

- Day 268. Berlin State Opera House

- Day 269. Tanglewood Music Festival

- Day 270. Orff and Old Spice®

- Day 271. Neoclassicism

- Day 272. Mass

- Day 273. Jean Sibelius (1865–1957)

- Day 274. Music for 18 Musicians

- Day 275. I Pagliacci (Clowns)

- Day 276. The Celesta

- Day 277. Getting Lost in Opera

- Day 278. Eszterhaza

- Day 279. Marlboro

- Day 280. The Barber of Seville and Ragú®

- Day 281. Electronic Music/Music Concrète

- Day 282. Trio Sonata

- Day 283. George Frideric Handel (1685–1759)

- Day 284. Symphony No. 40

- Day 285. Hänsel und Gretel (Hansel and Gretel)

- Day 286. The Harp

- Day 287. Atonality and German Expressionism

- Day 288. Walt Disney Concert Hall

- Day 289. Lucerne Festival

- Day 290. Turning Classical into Rock

- Day 291. Contemporary Music (1945–1970)

- Day 292. Rotational Form

- Day 293. Franz Joseph Haydn (1732–1809)

- Day 294. Meditation

- Day 295. La Bohème (The Bohemian)

- Day 296. The Classical Guitar

- Day 297. Arnold Schoenberg and 12-Tone Music

- Day 298. Opernhaus, Zurich

- Day 299. American Classical Music Hall of Fame

- Day 300. Rock Band Yes and Classical Music

- Day 301. Postmodern Music

- Day 302. Prelude

- Day 303. Sir Edward Elgar (1857–1934)

- Day 304. Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2

- Day 305. Tosca

- Day 306. The Pipe Organ

- Day 307. Bloop! Bleep! Every Element Can Be Serialized!

- Day 308. Teatro Carlo Felice

- Day 309. Monteverdi Festival

- Day 310. Classical Melodies in Rock Music

- Day 311. Minimalism (1960S and ’70s)

- Day 312. Chaconne

- Day 313. François Couperin “le Grand” (1668–1733)

- Day 314. Messiah

- Day 315. Madama Butterfly (Madame Butterfly)

- Day 316. The Bagpipe

- Day 317. “Chance,” “Aleatory,” or “Stochastic” Music

- Day 318. Mozarteum

- Day 319. Bachfest Leipzig and Bach Museum

- Day 320. The Beatles

- Day 321. Neoromanticism (1930S, 1950S, and Now)

- Day 322. Fantasia

- Day 323. Robert Schumann (1810–1856)

- Day 324. Träumerei

- Day 325. Turandot

- Day 326. The Human Voice

- Day 327. The Sensuous, Whole-Tone French

- Day 328. Großes Festspielhaus

- Day 329. Verdi Festival

- Day 330. The More, the Merrier

- Day 331. Postminimalism/Totalism

- Day 332. Character Piece

- Day 333. Clara Schumann (1819–1896)

- Day 334. Symphony No. 9 in D Minor (“Choral”)

- Day 335. Salome

- Day 336. The Serpent

- Day 337. Musique Concrète and “Found Objects”

- Day 338. National Theater and Concert Hall

- Day 339. Beethoven-Haus Bonn Museum

- Day 340. Sarah Brightman

- Day 341. New Simplicity and New Complexity

- Day 342. Cyclic Form

- Day 343. Amy Beach (1867–1944)

- Day 344. The Swan

- Day 345. Elektra

- Day 346. The Glass Armonica

- Day 347. American Jazz and Rock

- Day 348. Festspielhaus

- Day 349. Festival of the Sound

- Day 350. Classical Crossover

- Day 351. Art Rock Influence

- Day 352. Tone Poem

- Day 353. Maurice Ravel (1875–1937)

- Day 354. Mass in B Minor

- Day 355. The Consul

- Day 356. The Vibraphone

- Day 357. Music Theory and you

- Day 358. Berlin Philharmonie

- Day 359. Spoleto Festival

- Day 360. Classical Music’s Influence on Film and Television Composers

- Day 361. World Music Influence

- Day 362. Invention

- Day 363. Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840–1893)

- Day 364. Wiegenlied (Lullaby)

- Day 365. Amahl and the Night Visitors

- Copyright Page