![]()

CHAPTER 1

THE ASIAN STEPPES:

AN INTENSELY HOSTILE WORLD

NOTHING COULD HAVE PREPARED THE POPE’S EMISSARY FOR THE STEPPES OF MONGOLIA. JOHN OF PLANO CARPINI WAS A FRANCISCAN FRIAR AND A SON OF THE CENTRAL ITALIAN PROVINCE OF UMBRIA, A LUSH, GREEN COUNTRY OF WHEAT FIELDS, VINEYARDS, AND OLIVE GROVES. MONGOLIA WAS A DIFFERENT AND, TO FATHER JOHN’S EYES, AN INTENSELY HOSTILE WORLD. WITH CLASSIC UNDERSTATEMENT, HE RECORDED IN HIS HISTORY OF THE MONGOLS, “THE WEATHER THERE IS ASTONISHINGLY IRREGULAR.”

“In the middle of the summer when other places are normally enjoying very great heat,” he observed, “there is fierce thunder and lightning which cause the death of many men, and at the same time there are very heavy falls of snow. There are also hurricanes of bitterly cold wind so violent that at times men can ride on horseback only with great effort.”

It was Pope Innocent IV who had sent Father John on this diplomatic mission to Güyük, Genghis Khan’s grandson, who was about to become the new Mongol khan. In part, Innocent wanted to negotiate a treaty to prevent any more Mongol invasions such as Europe had suffered during the years 1237 to 1242. The pope also wanted intelligence regarding the Mongol military, and insights into how the Europeans could drive back any subsequent Mongol attack. Furthermore, word had reached Europe that it was the policy of the Mongol khans to treat clergy of all religions with deference, and tolerate all religions. Hoping to build upon Güyük’s open-mindedness, Pope Innocent wrote two letters to the khan explaining the basics of Christianity and urging him to be baptized. Innocent explained that as Christ’s representative on Earth, it was his responsibility “to lead those in error into the way of truth and gain all men for Him.” If Güyük were baptized, the odds were good that the rest of the Mongols would convert, too, because history had taught the Catholic Church that once a king entered the Church, his people followed.

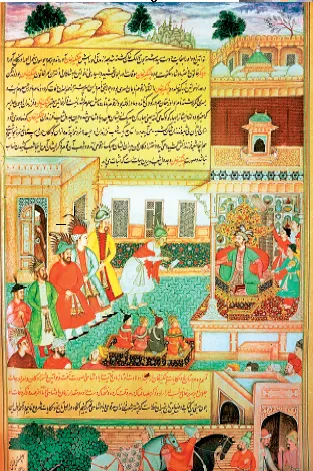

Genghis Khan, seated on a raised dais, greets his four sons, Jöchi, Chagatai, Ögödei, and Tolui. Of these four, only Ögödei would become Great Khan. akg-images / Werner Forman

In 1245, the year the pope gave him his assignment, Father John was sixty years old—an old man by the standards of the thirteenth century—but he was hardy, with a gift for languages, and experience representing the interests of the Catholic Church and his religious order, the Franciscans, in Europe and North Africa. He traveled with a fellow Franciscan, Benedict the Pole, and together they set out from Poland for the Mongol-occupied territories of the Ukraine and Russia.

In his narrative of their expedition, John records that as they set out on their mission he and Benedict “feared that we might be killed by the Tartars [John’s term for the Mongols] or other people, or imprisoned for life, or afflicted with hunger, thirst, cold, heat, injuries and exceeding great trials almost beyond our powers of endurance—all of which with the exception of death and imprisonment for life fell to our lot in various ways in a much greater degree than we had conceived beforehand.”

The Mongol commanders whom John and Benedict met in the Ukraine and Russia recognized the importance of their mission and hurried them from one outpost to the next so they would arrive at Karakorum, the Mongol capital, in time to witness Güyük’s inauguration as Great Khan. Their Mongol guides forced the two friars to ride at top speed, stopping five or six times per day at way stations where the entire party changed to fresh horses. Father John never became accustomed to the awkward size of Mongol horses—the horse’s wide belly stretched his legs uncomfortably, and every jolt as the pony trotted across the steppe sent a spike of pain up his spine.

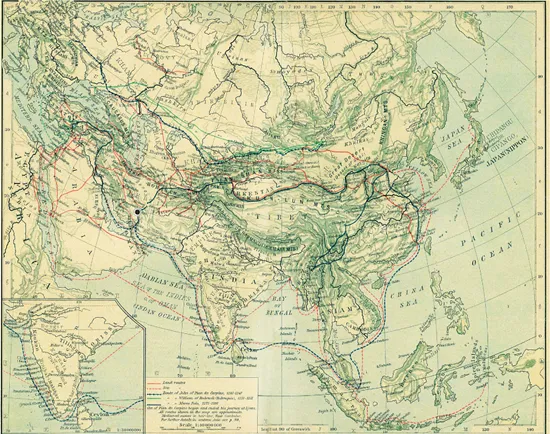

This map shows the route of Father John of Plano Carpini, Pope Innocent IV’s emissary to Güyük, grandson of Genghis Khan. It took Father John nearly six months to reach Güyük, after enduring storms of snow, dust, and hail.

The five-and-a-half months John spent riding through the mountains and deserts of Central Asia were wretched and often terrifying even for a tough, disciplined man possessed of a sense of mission. He and Benedict were traveling during Lent, when they were forbidden to eat meat or dairy products. Consequently, their diet consisted of millet boiled in water and seasoned with salt. “We were so weak,” John recalled, “we could hardly ride.”

“NOW YOU SHOULD SAY WITH A SINCERE HEART, ‘I WILL SUBMIT AND SERVE YOU.’ . . . IF YOU DO NOT OBSERVE GOD’S COMMAND, AND IF YOU IGNORE MY COMMAND, I SHALL KNOW YOU AS MY ENEMY.”

—A letter from Güyük Khan, Genghis Khan’s grandson, to Pope Innocent IV

Even when at last he reached the safety of the khan’s camp, Father John had no comfort: he arrived in the middle of a blinding dust storm. To keep from literally being blown away, Father John and his companions had to lie flat on the ground as great clouds of stinging dust swirled around them. Then, as the Mongols were preparing for the coronation of Güyük, a violent hailstorm struck, leaving deep piles of hailstones throughout the camp. This aberration was followed immediately by a heat wave that melted the hailstones so quickly as to produce a flash flood that washed away tents and drowned 160 men.

“To conclude briefly about this country,” John wrote, “it is large, but otherwise—as we saw it with our own eyes during the five and a half months we traveled about it—it is more wretched than I can possibly say.”

Many months later, when Father John returned safely to Europe, he brought to the pope a menacing letter from Güyük Khan. In a haughty tone, Güyük dismissed out of hand the idea that he “should become a trembling Nestorian Christian, worship God and be an ascetic.” Then the khan turned the tables on the pope. “Now you should say with a sincere heart, ‘I will submit and serve you.’ Thou thyself, at the head of all the Princes, come at once to serve and wait upon us! At that time I shall recognize your submission. If you do not observe God’s command, and if you ignore my command, I shall know you as my enemy.”

LIFE ON THE STEPPE

No one knows where the Mongols came from. Their language is said to be part of the Turkic-Manchu family, which suggests the Mongols could be related to the Turks, or to the people of Manchuria, or both. Another theory proposes that they are from the same ethnic group as the Huns who devastated the Roman Empire in the fifth century C.E. Ancient Chinese sources tell of a fierce warrior nation called Hsiungnu—perhaps these were the Mongols.

The most that can be said with certainty is that, according to the Chinese sources, by 400 B.C.E., there were a people dwelling in the vast grasslands far to the north of China. They were nomads who moved their flocks of sheep and herds of cattle and horses from summer pastures on the open steppe to winter pastures in sheltered valleys. Our Chinese informant adds that these nomads sheltered in round felt tents and had no written language.

Although the term Mongol suggests a unified nation, they were not truly united until Genghis Khan made them one. For most of their history, they were a collection of independent tribes and clans who formed temporary, ever-shifting alliances. Loyalty among the Mongols was limited to a small circle of people. There were chiefs with authority over these loose coalitions, but there was no central authority, no king, no emperor, no khan of all the Mongols (although Genghis’s great-grandfather had almost achieved that goal).

In most times this spirit of independence was tempered by a necessity for the Mongols to cooperate with each other. The steppe is immense, stretching from Hungary to the west and the mountains of Manchuria to the east, from the forests of Siberia to the north and the sand-and-gravel wasteland of the Gobi Desert to the south. In summer, temperatures can soar to 104° Fahrenheit (40° Celsius)—and there is no shade. In winter, temperatures drop so far below freezing that frostbite can occur in minutes.

But even in fine weather the steppe is unsettling: it is a vast ocean of grassland with few landmarks to assist travelers and no cities or towns to offer security, only the isolated tribes who may or may not consider the traveler an enemy. To travel across the bleak, empty steppe is to feel at all times exposed, isolated, and unprotected.

In spite of hundreds of thousands of square miles of lush grassland, the steppe is not suitable for farming—the soil is poor, and the growing season is only four months long. The Mongols adapted to this harsh land, becoming nomadic herders, primarily of sheep, who supplied meat, milk, cheese, wool, and felt for the Mongol tents, which are known in the West as yurts; the correct term is ger, pronounced with a hard g and rhyming with “dare.”

Bow Power

Historian and travel writer John Man tells how in 1794 a member of Turkey’s embassy staff in London gave a demonstration of the power of a composite bow. It was received wisdom in England that since the Hundred Years’ War of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, the English longbow was the deadliest weapon drawn by man. The Turkish archer Mahmoud Effendi, secretary to the Turkish ambassador in London, fired his arrows 415 yards (379 meters) against the wind, 482 yards (441 meters) with it. The English spectators were humbled—an arrow fired from an English long-bow rarely traveled 350 yards (320 meters). Mahmoud refused to accept any praise, however, saying that his master, the sultan in Constantinople, was so strong that his arrows traveled twice as far (a courteous although obvious exaggeration—no archer has ever shot an arrow half a mile).

In the nineteenth century, archaeologists discovered a stone stele in Mongolia dating from the 1220s and bearing an inscription that records an archery competition to which Genghis Khan was a witness. He had just returned from the conquest of what is now Turkistan, and to celebrate his victory Genghis called for a feast with the traditional Mongol games of wrestling, horse racing, and archery.

The inscription reads, “While Genghis Khan was holding an assembly of Mongolian dignitaries … Yesunge shot a target at 335 alds.” Yesunge was Genghis’s nephew, and apparently an extremely strong man, because an ald measures a little over 5 feet (1.5 meters). In other words, his shot traveled more than 1,675 feet (511 meters). No wonder Genghis erected a memorial to commemorate Yesunge’s feat.

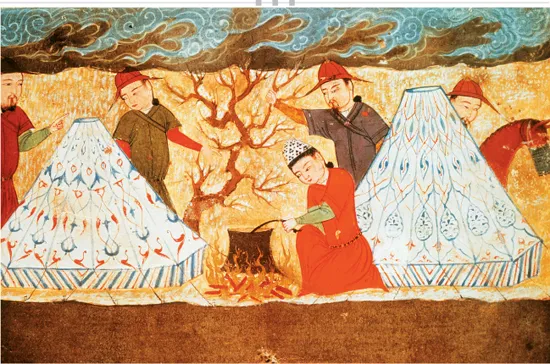

The traditional Mongol dwelling is a circular felt tent known as a

ger, also known as a

yurt. Persian carpers kept the ground inside the tent warm; the top was left open so smoke from the interior fire could escape. akg-images / VISIOARS

To erect a ger, Mongol women made a wooden lattice for the walls that they set up in a circle, with long wooden poles mounted on top to form the pointed crown of the tent. When the felt was hung on this frame, the topmost point was kept open so smoke from the interior central fire could escape. Inside, the ground was covered with Persian carpets; there were iron and copper cooking pots, steel swords and daggers, and luxury items such as little chests of tea and perhaps some silk garments. All of these things the Mongol family would have acquired either through trade with passing caravans or by looting the tents of rival Mongol tribes.

Although shorter than other breeds, the Mongolian horse is fast and hardy—essential qualities on the steppes. Mongols would frequently change horses, allowing them to cover 80 miles (128 kilometers) or more a day. akg-images

THE HORSE AND THE BOW

In addition to sheep, the Mongols also raised oxen to pull their heavy wooden carts and even some camels, but the steppe’s primary gift to the Mongols was a hardy breed of wild horse. Archaeological evidence tells us that 6,000 years ago the inhabitants of the steppe hunted wild horses for meat; 4,000 years ago they had domesticated them.

Compared to the thoroughbreds of the Western world, the Mongol horse is an unattractive animal—short, barely taller than a pony, with a thick neck, a big, distended belly, and a shaggy coat. But these horses are fast, and they can survive winter temperatures that would kill other breeds by digging through the snow with their hooves until they reach the frozen grass beneath. Even today many Mongols own at least one horse, and horse racing remains one of the “three manly skills” by which Mongol males prove themselves (the other two are archery and wrestling).

Because the Mongols did not grow crops of any kind, they had no beer or wine, but from mare’s milk the Mongols made koumiss, a kind of beer with a high alcohol content. There are many accounts of Mongol warriors and chiefs dying young as a result of heavy drinking.

Most historians and archaeologists believe the stirrup was developed in Central Asia, very likely by the Huns. The stirrup gave a rider stability on horseback while making it easier to maneuver his mount. The stirrup also enabled the Huns, the Mongols, and other mounted nations of Central Asia to fight o...