![]()

CHAPTER 1

Foxtrot to Destiny

The machine guns sliced through the formation like a scythe, leaving a windrow of dead and wounded Marines; a grotesque formation, the violently dead in postures impossible in life; the wounded, silent, sobbing or screaming, each alone and desperate within his own skin; their lieutenant, James Shelton, down, his head caved in and his thigh blown out.

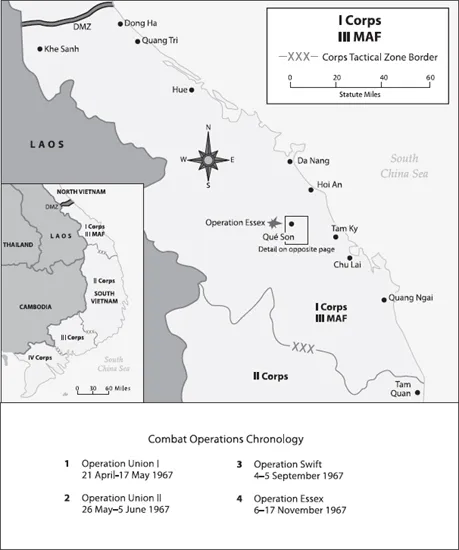

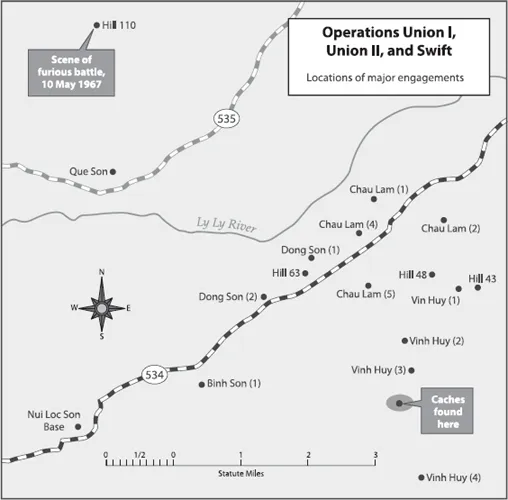

THESE MARINES, TWO PLATOONS OF THEM, from Capt. Gene Deegan’s1 Foxtrot Company, 2nd Battalion, 1st Marines (F/2/1)2 left the hill mass of Nui Loc Son in the dark that April morning in 1967, trying for all the world to maintain noise-discipline as they stole past somnolent villages toward their objective. Strangely, no dogs barked, but from out of the blackness a bell tolled: not a loud bell, but clear, its vibrations drifting across the valley floor. Dawn approached with tropical rapidity as Captain Deegan aligned the Marines of his 2nd Platoon on an east-west axis in a tree line, facing a tree-choked hamlet on the far side of a forty-meter-wide rice paddy.

Deegan’s other platoon, under Lt. James Shelton, moved stealthily eastward near the dirt and gravel track that the map optimistically called Route 534 and then made a large loop to get to the north side of the objective area. Between the dawn and the day, Shelton’s Marines struck like a hammer, sweeping southward on line, flushing a score of enemy soldiers, driving them toward the anvil—Deegan’s men. The enemy scattered like quail; some ran parallel to Shelton’s platoon, and his Marines shot them down; others perished in the fire from Deegan’s position, and a handful of survivors disappeared into the bush. After the smoke cleared and his men did a body count, Captain Deegan radioed the 1st Marines and reported the contact and eighteen enemy killed. He assured them that everything was under control, only one of his men was wounded, and he needed no help.

Marines approach the village of Binh Son (1) on April 21, 1967, during Operation Union I. The battle will become much enlarged as the Marines commit assets to deal with a very large enemy force. USMC

Lieutenant Shelton’s men stayed in place while Captain Deegan had the blocking-force Marines police up the battlefield, and he called for a medevac for his casualty. While waiting for the chopper, the captain moved among his troops and talked to them about what they had seen.

Gunfire shattered the stillness when one of the Marines cut loose with a full magazine of M16 rounds and another fired an M79 grenade launcher across a large paddy to their right. Privates First Class Lonnie Matthews and John Jackson told their lieutenant that they saw a bush move. Looking closer, they saw four heavily camouflaged North Vietnamese Army (NVA) soldiers, fired at them, and saw a couple go down. The lieutenant told these two Marines and another, Pfc. Thomas “Cotton” Holtzclaw, to take a look. They started out across the paddy but did not get very far before a smattering of enemy fire sent them scampering back to join the main body of troops. They were unscathed except for Holtzclaw, who was knocked to the ground when a bullet struck his boot heel.

Marines from the 2nd Battalion, 1st Marines, fight their way out of a tree line under enemy fire in an attempt to rescue wounded comrades on April 21, 1967, the first day of Operation Union I. USMC

Captain Deegan came over to take a look and then ordered an air strike on the tree line while he lined his Marines up to assault across the paddy and finish off the remaining enemy. His two platoons were about three hundred meters apart, and he ordered them to move toward the objective in a flying wedge.

Just as the air strike ended and the Marines began to move, Holtzclaw came up to Matthews and Jackson, shook their hands, and said, “It was nice knowing you. I am not going to make it.” Matthews and Jackson looked at each other and then at Holtzclaw. They told him that he would be okay.

The Marines confidently started across the paddy. The enemy let them get about halfway and then punched them hard with small-arms and machine gun fire. When Captain Deegan gave the order to attack, Lt. Mike Hayes,3 artillery forward observer (FO), was alongside Lieutenant Shelton and the platoon sergeant, Staff Sergeant Gould.

Lt. Mike Hayes: Shelton was hit almost immediately. We had Marines down, and about eight of them made it back to the paddy dike. Of the thirty-one in front of us, there was no way to know how many were killed or wounded.

BULLETS CUT DOWN PFC. HOLTZCLAW at once. Jackson and Matthews picked him up and were carrying him to the cover of a rice paddy dike when he was shot a second time. They lowered him to the ground and called for “Corpsman up.” “Doc” Jeffrey Bouton ran over amidst the fire, kneeled down beside Holtzclaw, shook his head, and said, “There is nothing we can do.” Then Bouton rose up, and the NVA shot him too.

Route 534: “the road of 10,000 pains.”

A battalion of Lieutenant Colonel Huyen’s 31st North Vietnamese Army Regiment (Red River Regiment) was dug in, and they were ready. They had laid communication wire, strung protective barbed wire in key spots, and positioned mortars inside of houses, the roofs of which were removable and screened the mortars from the air when in place. These mortars barked their presence as they went into action and quickly found the range of the Marines’ formation: a round impacted between Holtzclaw and Bouton and finished them both. Simultaneously, enemy small-arms fire hit Lonnie Matthews’s left arm and John Jackson’s right arm. Everybody around them lay dead or wounded. Captain Deegan motioned for Jackson and Matthews so they ran back to their skipper just as a round slammed into Deegan’s chest. Privates First Class Matthews and Jackson, each with one good arm, dragged Deegan behind a hut, where he commenced trying to radio for help.

A corpsman gave morphine to Deegan, which slowed down his thinking a bit, but he got on the radio and told his regiment that he needed all the help he could get, that the enemy had blown his attack formation apart, leaving the exposed paddy awash with dead and wounded Marines.

Just moments after the attack began, Lieutenant Hayes, the FO, was Foxtrot Company’s only unwounded officer. He did what he could to organize the Foxtrot Company survivors and summon artillery support. Communications with regiment and with the artillery batteries were complicated because Foxtrot Company had to relay their radio traffic through Deegan’s security platoon atop Nui Loc Son.

Deegan’s remaining Marines put out as much firepower as they could and held on for reinforcements. The large number of Marines lying in the paddies foreclosed on the option to withdraw. Each Marine lay there in his own small world, compressed to the twenty or thirty yards he could see, a world of heat and noise and smell and hundreds of flying hot steel fragments, any one of which could take away in an instant anything he ever was and anything he would ever be. He was fueled by fear, adrenaline, and a hyper-awareness of what was required of him.

Eighteen-year-old Pfc. Gary Martini rolled over a protective dike and wiggled in a low crawl across the paddy until he was fifteen meters from the enemy. He carefully raised his head to locate a target and one by one lobbed all his hand grenades among the NVA, killing several. He then crawled back through the fire to rejoin the survivors. Martini looked back at the wounded and dead Marines still in the paddy in front of him, turned around, and started out again. Though wounded himself, he ran a zigzag pattern into the killing zone, grabbed another Marine by his collar, and dragged him to safety. A close friend of his, Private First Class Boudreau, called him by name. Boudreau lay wounded less than twenty meters from the enemy. Again, Martini ran into the enemy fire. Hit another time, he shouted at the other Marines in the trench line to stay put and that he could get Boudreau in without help. In the last act of his life, Private First Class Martini pulled Boudreau to safety.

Lt. Mike Hayes: I told everyone to stay down and not attempt to go out. Martini literally broke out of my grasp and went out to aid Boudreau. Martini got hit in the thigh on the way out and in the upper chest just as he got Boudreau back. Now there were about six of us, and Boudreau. We talked to the people on Nui Loc Son who could see the battle and were told that the NVA had us surrounded. The only effective mortar fire support we were getting was from the Howtars on Nui Loc Son.

Pfc. Tom Holloran (with the 106mm recoilless rifles on Nui Loc Son): We could see hundreds of NVA, and we used all our mortar and 106 rounds trying to support our men.

DEEGAN’S SURVIVORS GRIMLY FACED THE BATTLEFIELD, expecting a counterattack at any time.

![]()

CHAPTER 2

Bald Eagle

RADIO OPERATORS IN COMBAT OPERATIONS centers (COCs) sat and waited like hotline counselors for fear-laden voices to murmur urgent, static-ridden pleas in their ears.

Sgt. Keith Lamb (artillery forward observer, 3rd Battalion, 1st Marines): We were all sitting around the COC. The day’s heat was starting, and the two small electric fans were having a hard time keeping the cigarette smoke down.

“Circumference, this is Chinstrap. Request you monitor frequency Mike 45.9.”

One of the radio operators switched frequencies to see what was going on. Someone yelled, “Go get the CO, we are on a Bald Eagle [reaction force]!”

The next thing we heard was Foxtrot Company: “Send help! We have made contact with a large enemy force and are being cut to pieces!”

“Mike Company, saddle up! Let’s go! We have five minutes to be in the LZ!”

An officer yelled at me, “Sergeant, where is the lieutenant? We need an arty FO.”

“Sir, he went up to Da Nang to division headquarters.”

“Okay, you’ll do. Get your gear and a radio and head for the LZ.”

I ran to my tent and grabbed whatever gear I could fit into my pockets, rounded up John Papcun and another Marine who volunteered as radio men, and headed for the LZ. We busted open cases of C-rations and took out the fruit and whatever else we could stuff in our pockets. Then we milled around, adjusting straps, checking weapons, and waited for the choppers to arrive. We waited for about forty-five minutes.

Lt. Frank Teague (platoon commander, Mike Company, 3rd Battalion, 1st Marines): I was sitting in a hooch reading Exodus when I got the word to go see the company commander, Captain Bill Wood. He said, “A company from 2/1 is missing. We lost radio contact with them.” We looked at each other, like what do you mean, missing? He said that they were over in 2/1’s TAOR, “and we don’t have any maps of this area, and we are gonna go find them. We’ll go in first and then India Company will come in with the battalion CP group. When we get to the LZ, we’ll send the three platoons out on compass bearings.”

About a week before that, we were issued the M16 rifle. It was a nightmare. Mine jammed all the time. Everybody had been trained on the M14, which was like your right arm, and we got this Tinker Toy that didn’t work. I remember thinking that I’m a college grad, and I’m having trouble with this friggin’ thing. Some of my men just don’t get this shit. This thing doesn’t work. So I was off on the Bald Eagle with my M16 in a garbage bag to keep the dirt out. My platoon was going to be first in the LZ, and I was afraid it was gonna be hot.

The helicopters landed and throbbed with impatience as the Marines formed single files, ducked to run under their blades, and boarded. The whirling blades blew dirt, pebbles, and vegetation on the Marines, stinging bare skin where they hit; they blew helmets off and maps out of one’s hand. Helicopter crewmen in brightly colored and dark-visored helmets, tethered by the umbilical cords of their radio cables, solemnly stood by their machine guns. All aboard. The pilots raised the ramps, revved up the rpm, lifted a bit off the ground, leaned the birds forward, and took off.

Lance Cpl. Jim Mullen (radio operator for the forward observer): The door gunner began firing, and the guy next to him said, “What do you see, what do you see?” He said, “I see platoon of NVA in the open.” I crossed myself and did an act of contrition. Lieutenant Bishop was right across from me, and his eyes got as big as saucers.

Sgt. Keith Lamb: It seemed like a long, long way. Everyone was nervous, and quiet. We knew we were going into a hot LZ. The moment came. No one hesitated. We were lying in rice stubble as the helicopters sped away. Everyone seemed to be firing; bullets were coming from everywhere....