![]()

CHAPTER ONE

THE ROAD TO WAR

With apparent disregard for the columns of US Marines on the road, South Vietnamese natives walk the center lane. The Marines are on a reconnaissance mission west of the Da Nang Air Base.

President Lyndon Baines Johnson assumed power on November 22, 1963, in the wake of the most shocking national event since the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. “Everything was in chaos,” Johnson would later recall. “We were all spinning around and around, trying to come to grips with what had happened, but the more we tried to understand it, the more confused we got.” Uncertain of his legitimacy in the eyes of the American people, the new president clothed himself in President Kennedy’s mantle, vowing to carry forward the work his martyred predecessor had left undone—protecting the civil rights of African Americans, ameliorating the hardships of the poor, and defending South Vietnam from the threat of Communist aggression.

The growing conflict there was extremely vexing to Johnson, who was much more comfortable in the realm of domestic politics and saw Vietnam as an unwelcome distraction. As he would later say, “that bitch of a war” came between him and “the woman I loved—the Great Society,” but he fully appreciated its political significance, both for himself and the Democratic Party. “I am not going to lose Vietnam,” he told Ambassador to Vietnam Henry Cabot Lodge less than forty-eight hours after Kennedy’s death. “I am not going to be the president who saw Southeast Asia go the way China went.”

Johnson’s rhetoric reflected his shrewd appreciation of the national mood in the aftermath of Kennedy’s death, but his commitment to Vietnam had deeper and more important roots. There were, to begin with, the lessons of Munich and the geopolitical imperatives of the Cold War, which presented the world as communism versus democracy. Like many of his generation, Lyndon Johnson remembered all too vividly what appeasement of Hitler had purchased in 1940. Behind Hanoi’s bellicosity, Johnson saw the aggressive hand of a Communist China intent on dominating the entire Southeast Asian peninsula. Should the United States fail to meet this challenge, Johnson believed, it would not only cost the South Vietnamese their freedom but also have “profound consequences everywhere.”

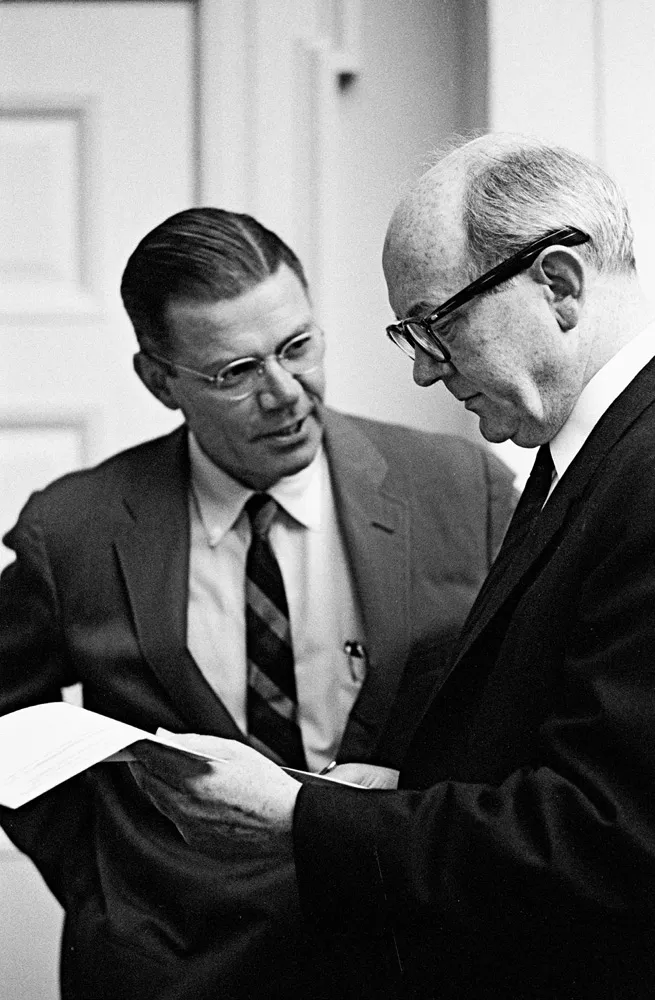

Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara (left) confers with Secretary of State Dean Rusk at the White House, July 1965.

If Vietnam was a trial of US credibility and resolve, it was also a personal challenge. For all his mastery of domestic politics, the new president had little experience in foreign policy, a point made repeatedly by those in the press who doubted his capacity to handle the complex problems of international affairs. His sensitivity on this issue led him to retain Kennedy’s top foreign policy advisors—men like Rusk and Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara—who had their own stake in South Vietnam’s survival.

Compounding matters was the sense of crisis enveloping Southeast Asia at the end of 1963. In Indonesia, the mercurial President Sukarno had gone from flirtation with Peking to open war against the pro-Western government of Malaysia. In Cambodia, Prince Norodom Sihanouk had renounced American aid and called for an international conference to guarantee his nation’s neutrality. The same theme was trumpeted by President Charles de Gaulle of France, who challenged American influence in southern Asia with a proposal for the neutralization of South Vietnam.

Meanwhile, the military junta that took power in Saigon after the coup that deposed Ngo Dinh Diem was not able to either fill the political vacuum left by Diem’s death or cope with the upsurge of fighting that wracked the countryside. On December 21, Robert McNamara returned to Washington after a brief inspection tour with a grim report of political turmoil, administrative paralysis, and military reverses at every hand. Unless the situation was stabilized immediately, warned the secretary of defense, the fate of South Vietnam would be “neutralization at best and more likely a Communist-controlled state.”

Concerned for his own political standing and the credibility of America around the world, determined to show his critics he could deal with the crisis he had inherited, Johnson responded by vigorously affirming his government’s intention of resisting communism in Southeast Asia. He expressed his resolve in terms of America’s global responsibilities. “Our strength imposes on us an obligation to assure that this type of aggression does not succeed,” Johnson wrote in February 1964. Neutralization was unworkable, withdrawal unthinkable.

For all that, the new president proceeded with restraint during his first year in office. One reason for the measured pace was Johnson’s reluctance to employ American military power on a large scale so far from home. No more than Kennedy or Eisenhower did he relish the prospect of US troops engaged in battle on the Asian mainland. Nor was Johnson certain how the Soviets or Chinese would react to the appearance of American combat forces in the region. Moreover, American assumption of responsibility for the war might seriously undercut South Vietnam’s will to defend itself.

Even more important were the potential domestic repercussions of greater US involvement in Southeast Asia. Any significant American escalation would endanger the administration’s legislative program and jeopardize Johnson’s bid for election in November. Johnson was not only unwilling to let this happen, he saw no reason for it. Preoccupied with establishing his leadership and taking advantage of the moment to push major civil rights and antipoverty bills through Congress, the president balanced commitment with caution, putting off difficult decisions for as long as possible—1964 was, after all, an election year, and Johnson did not want to rock his own boat any more than necessary in an election year.

Thus, for all the upheavals of the previous six months, the spring of 1964 witnessed little apparent change in the course of US policy. After a review of the options available to him, Johnson authorized the deployment of additional US military advisors and an enlargement of the economic assistance package to Saigon. The emphasis, however, remained squarely on the South Vietnamese, with new plans for an increase in the size of the ARVN, intensification of the pacification program, and stepped-up military operations against the Viet Cong (VC).* “The only thing I know to do,” Johnson told Sen. William Fulbright in March, “is more of the same, and do it more efficiently and effectively.”

Yet hidden from public view were important changes that, like the heightened rhetoric of US commitment, contained a momentum of their own. Concerned over reports of increased infiltration of men and supplies flowing south, the administration approved a program of clandestine operations into Laos and North Vietnam. Pressed by McNamara for concrete steps to counter the continuing military decline on the ground, the president authorized contingency planning for retaliatory air strikes north of the demilitarized zone (DMZ). Determined to demonstrate American resolve, Johnson privately warned Hanoi that continued support for the insurgency could bring the “greatest devastation” to North Vietnam. Taken as a whole, these measures revealed a fundamental shift in perspective, a growing belief in Washington that direct action against North Vietnam could somehow achieve what US policy had failed to accomplish in the South.

Vietnamese Army personnel train in the jungle.

Civilian Irregular Defense Group (CIDG) training of South Vietnamese civilians.

For the time being, the counterinsurgency war in the South continued, with the US more deeply involved than ever. Over the next nine months, the number of American military advisors increased from sixteen thousand to twenty-three thousand, among them naval officers working with the fledgling Vietnamese navy, and nearly one hundred US Air Force pilots flying combat-support missions for ARVN offensives as well as training Vietnamese pilots. The US Army was also becoming increasingly engaged in the shooting war. By the end of 1964, American Special Forces Civilian Irregular Defense Group (CIDG) teams had established forty-four camps throughout South Vietnam. Many of them were located along the Laotian border, enabling the Green Berets and their Montagnard allies to monitor traffic along the Ho Chi Minh Trail, but also making them more vulnerable to Communist attack. From 1960 through 1962, thirty-two US military personnel lost their lives in South Vietnam. During 1963 that figure climbed to seventy-seven, and in 1964, deaths from hostile action totaled 137. While the numbers were still low, the trend was disquieting.

But US servicemen were not the only Americans struggling to contain the Communist guerrillas. In the late spring, Frank Scotton, a junior field operator with the United States Information Service, unveiled the first People’s Special Forces group—six-man teams of armed Vietnamese civilians trained to fight local insurgent bands on their own terms. By August, the program had been taken over by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), which also provided arms and funding for Vietnamese Counter-Terror Teams and sponsored Radio Freedom, a ten-thousand-watt station based in Hue that sent propaganda broadcasts to North Vietnam.

US Marines from the 3rd Air Delivery Platoon, Da Nang, parachute from a Marine C-130 Hercules transport aircraft during a resupply mission to a US Army Special Forces camp.

Alongside these “public” activities was an expanding program of US-directed covert operations. Some were run by the US Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV), such as Project Leaping Lena, which sent eight-man squads of Vietnamese commandos on long-range reconnaissance patrols into Laos, or Project Delta, in which ten-man “Hunter-Killer Teams” made up of American and Vietnamese Special Forces soldiers penetrated enemy-controlled territory within South Vietnam. The most dramatic covert activities, however, were carried out by the innocuously named Studies and Observation Group (SOG), a highly classified unit controlled directly by the Pentagon. SOG teams entered Cambodia, Laos, and even North Vietnam to gather intelligence on enemy activities, snatch prisoners for interrogation, and interdict infiltration. SOG also sent Vietnamese PT boats against North Vietnamese coastal installations in a series of raids code-named Operation 34-Alpha.

Staff Sergeant Howard Stevens, Special Forces advisor to a Montagnard strike force, reads his mail at Phey-Shuron, a camp built in the central Vietnam highlands. Stevens was part of a twelve-man team making soldiers of Koho tribesmen in the jungle mountains west of Da Lat.

Unfortunately, the dispatch of additional advisors, the expansion of covert operations, and an increase of $125 million in aid were not able to arrest the steady decline of Saigon’s military and political fortunes. The junta that had deposed Diem was itself overthrown two months later by a group of younger officers under the leadership of Gen. Nguyen Khanh. Although Washington lent Khanh vocal public support, the new government was no more successful than its predecessor in extending its authority into the countryside. A US report issued on April 1 estimated that the Viet Cong controlled between 40 and 60 percent of the rural population. Even in areas that Saigon could claim as its own, a lack of trained officials, bureaucratic lethargy, insufficient resources, pervasive corruption, and the sometimes brutal behavior of government soldiers undermined the new pacification program and prevented the implementation of ambitious development plans drafted by the Americans.

Although Khanh proved inept at rallying public support, his main problem was the steadily worsening military situation. In December 1963, as Viet Cong units roamed at will over large sections of the South Vietnamese countryside, the central committee of the Vietnamese Communist Party met in Hanoi to approve a new strategy for the southern insurgency. Hoping to discourage the US and bring down the Saigon government, North Vietnam funneled increasing amounts of war materiel to its southern allies, who began to take to the field armed with mortars, machine guns, and recoilless rifles.

Unable to solve the problems that surrounded him, Khanh called upon his countrymen to “March North,” a cry echoed immediately by Gen. Nguyen Cao Ky. The flamboyant young commander of the Vietnamese air force publicly announced that his pilots had already been tr...