CHAPTER ONE: WORLD WAR I

WIND IN THE WIRES

On August 4, 1914, German troops set foot on Belgian soil. Treaty-bound France, Britain, Italy, Austria, and Russia were irrevocably committed, and all of Europe was officially at war. It would be a war of extremes—of mud, mass slaughter, and stalemate; of technological marvels, and of the birth of a new type of warrior. Barely eleven years after the Wright Brothers took their first flight, this new war would take to the skies.

Army commanders on both sides believed the coming confrontation would be a land campaign. Air power, still an unknown, would play a minor role at best. Early experiments in 1910 had proven that the best role for the airplane would be reconnaissance. French army maneuvers in 1911 consistently showed that airplanes could locate enemy troops some 37 miles (60 kilometers) away.

After every war soldiers of all stripes disparage the generals and politicians for their lack of foresight and inability to properly prepare for the next war. The newly minted airmen of World War I drew especially bitter pleasure from this pastime. Often-repeated stories focused their venom on the great men who had dismissed the importance of the aeroplane. Britain’s generals Sir William Nicholson and Sir Douglas Haig suggested before the war that aircraft would never be of any use to the army. In truth, however, the major world powers had already begun to build up their air forces with remarkable rapidity shortly before the opening of hostilities.

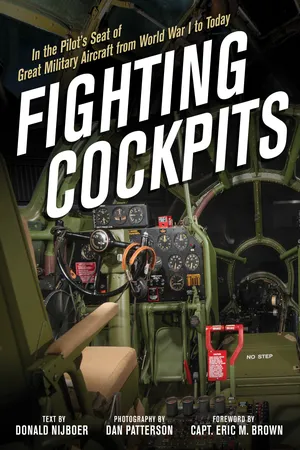

An S.E.5a cockpit section revealed. This simple, wire-braced, box-girder wooden construction was typical for a World War I scout.

In August 1914 the nations of Europe mobilized more than six million men for battle. That total, however, included fewer than two thousand pilots and one thousand aircraft. The fragile wood-and-canvas open-cockpit planes that dominated both sides at the beginning of the war were all spectacularly slow. The Blériot XI, made famous by Louis Blériot when he flew across the English Channel in 1909, equipped seven British, eight French, and six Italian squadrons at the outbreak of war. For all its fragility, the Blériot XI was leading-edge technology. Cockpit “instrumentation” consisted of a watch and a map of the flight route rolled onto a scroll. Airspeed and altitude were left to the pilot’s judgment.

What set the Blériot apart from its contemporaries was its flight controls. Rather than the prone position the Wright Brothers used in their Flyer, Blériot put the pilot in a sitting position and equipped him with left and right foot pedals to control the rudder and a single control stick (joystick) between the pilot’s legs that moved forward and back, causing the nose to pitch up or down. It’s a system that is used to this day.

Advanced as the Blériot was, it still represented stagnation in aircraft design. All design choices had tradeoffs in performance. A long-range aircraft needed to be large to hold more fuel and offer more for long-duration flights. To be fair, most airplane designers still had only a vague idea of how to design an airplane for a specific military job. In fact, they had no idea what types of aircraft would be needed for the upcoming war. Fighters and bombers didn’t exist, and most believed aircraft would be used for reconnaissance only.

The focus on aircraft design and engine development left little time for the evolution of the cockpit. What the pilot needed to command his machine and what he had to endure while flying were afterthoughts. Throughout World War I designers were busy mastering the art of aircraft weight distribution. Critical items such as guns, bombs, fuel, and crew had to be carefully judged and applied to any new design. For example, the Sopwith Tabloid weighed less than 1,200 pounds (544 kilograms). The engine accounted for 38 percent of that weight; the airframe for 30 percent; and the fuel for 15 percent. The remaining 17 percent was allocated for the pilot and camera or armament. The cockpit—including its equipment and instrumentation—had to be simple and light.

Blériots were widely used by the Allies at the outbreak of World War I. Instruments were unheard of in early aircraft and the Blériot was no exception. A watch and a map rolled onto a scroll were the pilot’s only aids. Height and speed were left to the airman’s judgment.

In Britain the Royal Aircraft Factory led the way in designing, testing, and building most military aircraft. For reconnaissance the Royal Aircraft Factory believed the slowest possible speed an airplane could be made to fly was best. It seemed counterintuitive and as a result the Royal Flying Corps would use the Royal Aircraft Factory B.E.2 as their principal machine for the first two years of the war. Equipped with two open cockpits, it had a top speed of about 75 miles (121 kilometers) per hour and took more than half an hour to climb to 10,000 feet (3,048 meters). Cockpit instrumentation was sparse with just a clock, altimeter, and engine rev counter (tachometer). While inherently stable it was an unmaneuverable craft that made easy fodder for early German fighters. Baron Manfred von Richthofen (also known as “the Red Baron”) feasted on the slow-flying B.E.2, which accounted for twenty-five of his eighty victories. The German equivalent of the B.E.2 was the Taube monoplane. Powered by a 120-horsepower Mercedes six-cylinder engine, it had a top speed of 62 miles (100 kilometers) per hour.

Many early aircraft had no cockpit whatsoever. Patrick N. L. Bellinger, naval aviator No. 8, is pictured in a Curtiss A1 seaplane in 1915. The A1 had no fuselage or canvas protection for the pilot; he sat exposed to the elements, with just a safety belt and life preserver as lifesaving equipment. National Naval Aviation Museum

Flying during World War I was a physically demanding job. Very little was available, via cockpit design, to mitigate the situation. The airstream in an open cockpit could be brutally cold, especially during winter. Frostbite was common, forcing pilots to smear their faces with thick layers of grease for protection, and heavy clothing was also mandatory. Pilots flying at high altitudes often suffered from dizziness and blackouts. In addition, rotary engines sprayed castor oil into the airmen’s faces, often inducing chronic nausea and diarrhea.

Physical exertion was constant for the pilot, with the rotary engine–powered aircraft being the most punishing. The gyroscopic force of the engine had to be continuously countered in order to maintain straight and level flight. There was no equipment or instrumentation to relieve the discomfort.

And while pilots experienced the joy and grandeur of flight, they also faced death in particularly gruesome manners. The odds of a pilot dying, becoming injured, or being captured was no better than fifty-fifty. If not killed outright by an explosive or incendiary bullet, the biggest fear was death by fire. Exposed fuel lines and gas tanks were almost always fitted in front or above the cockpit. An airman caught in a burning machine had three options: jump, stay and burn to death, or shoot himself with a revolver. For some, however, there was a lifesaving solution.

Parachutes had existed since the end of the eighteenth century and were used for exhibition jumps from balloons. In 1912 jumps from aircraft proved successful, and during the war parachutes were issued to airship and kite balloon observers. The Germans eventually adopted the parachute for airplane pilots, but the British never did (their pilots were given a revolver—not exactly a morale-boosting device). The Deutsche Luftstreitkräfte (German Air Force) began issuing parachutes to pilots and observers in the spring 1918. By that summer Allied pilots watched with envy and consternation as German pilots jumped from their burning machines and parachuted slowly and safely to earth. The Allies’ disregard for the parachute was criminal. Not a single Allied aircraft parachute was issued during the war.

Before the war aircraft typically had no more than one or two flight instruments in the cockpit. During the war few aircraft had more than seven: airspeed indicator, altimeter, bubble lateral level, compass, fuel-pressure gauge, pulsometer for monitoring engine performance, and clock. But as the war progressed more controls, equipment, and switches were added.

Aerial reconnaissance—observation and artillery spotting—were the prime missions flown by both sides in the early stages of World War I. In a few short months these missions became indispensable, which meant a new task for the pilot. Box cameras were mounted vertically to the starboard outsides of cockpits, allowing the pilot to change glass plates while in flight. Entire attack and artillery-fire plans were meticulously formulated based on the photographic evidence gathered by airmen—and that’s when the shooting started.

World War I aviators soon realized they could do more than simply wave as they passed one another in the air. Some wasted no time in trying to shoot down their foes. Pistols, rifles, and even hand grenades were soon brought aloft but with mixed results. What began as something of a game suddenly took on a more serious military purpose. By 1915 the British General Staff reported that aerial “fighting would be necessary on an ever increasing scale to secure liberty of action for our artillery and photographic machines, and to interfere with similar work on the part of the enemy.” The fighter plane was born.

The world’s first true fighter aircraft appeared in the form of the German Fokker E.I monoplane. A new piece of equipment was introduced into the Fokker cockpit, and on August 1, 1915, soon-to-be-ace Max Immelmann scored the first success with it. What set the Fokker E.I apart from all Allied armed aircraft was its synchronized machine gun firing between the propeller blades. The Fokker’s single 7.92-m...