![]()

CHAPTER 1

THE WHISKEY REBELLION

GEORGE WASHINGTON

AT DAWN ON JULY 16, 1794, JOHN NEVILLE, SIXTY-THREE YEARS OLD, CLIMBED out of bed and began to dress. His preparations for a new day, however, were interrupted by the noise of a large crowd gathering outside his house. A veteran of the American Revolution in which he had risen to the rank of brigadier general, Neville was one of the wealthiest men in the western counties of Pennsylvania. His estate, Bower Hill, in the Chartier Valley outside of Pittsburgh, extended over more than a thousand acres. In addition, Neville owned eighteen slaves, ten horses, sixteen head of cattle, and twenty-three sheep. He also drew a salary as the region’s inspector for the collection of a federal tax on whiskey and all other distilled spirits.

The men who stood outside General Neville’s door were not wealthy. Few, if any, in the crowd owned more than a hundred acres of farmland. Most had little or no cash; they used the whiskey they distilled on their farms to barter for the necessities they could not produce themselves. The government’s new ten-cent tax on every gallon of whiskey hit these men hard, and so they refused to pay it.

The day before, Neville had acted as guide for a federal marshal, David Lenox, who had come into the country to serve writs on backwoodsmen who were delinquent in paying the whiskey tax. Some of the men outside Neville’s house had been served, and they were angry about it. Standing at his threshold, Neville demanded to know what the crowd wanted. They said they wanted Lenox to come to them. They said Lenox’s life was in danger, and they had come to protect him. Neville didn’t believe a word of it, and besides, Marshal Lenox was not there. The general ordered the crowd off his property, and when they refused to go, he grabbed his gun and fired into the mob. A musket ball struck and killed one of the crowd’s leaders, Oliver Miller. As Miller fell, the mob raised their own muskets and fired on the house. Neville slammed the door shut and bolted it, then seized a signal horn and gave a long, strong blast. Suddenly, the crowd’s flank was raked by repeated shotgun blasts from the slave quarters. Neville’s slaves had armed themselves and were fighting for their master. The mob stood their ground for another twenty-five minutes, firing at the main house and the slave quarters, but after six of their men lay wounded on the ground, the backwoodsmen lifted their injured companions, picked up Miller’s body, and retreated.

![]()

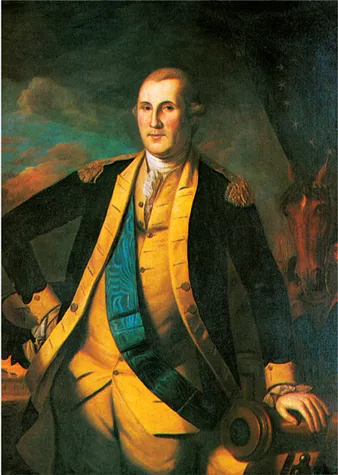

AFTER HIS TRIUMPH OVER THE BRITISH IN THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION, GEORGE WASHINGTON WAS ALMOST UNIVERSALLY REVERED AS A NOBLE, SELFLESS PATRIOT WHO COULD UNITE THE FLEDGLING UNITED STATES.

![]()

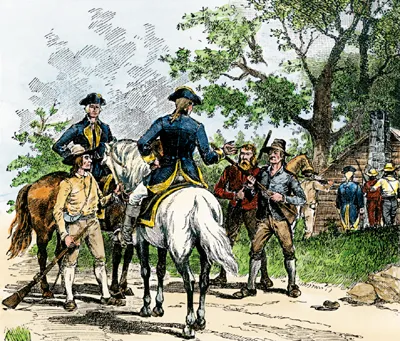

GOVERNMENT OFFICIALS WHO ATTEMPTED TO COLLECT THE WHISKEY TAX IN PERSON OFTEN CAME UP AGAINST SHORT-TEMPERED, WELL-ARMED FRONTIERSMEN.

![]() The clapboards of Neville’s house were pockmarked with bullet holes, but no one inside had been injured. Nonetheless, the general expected the mob would be back and with a larger force. He sent a note to his son, Presley Neville, in Pittsburgh with instructions to bring the militia immediately to help defend Bower Hill.

The clapboards of Neville’s house were pockmarked with bullet holes, but no one inside had been injured. Nonetheless, the general expected the mob would be back and with a larger force. He sent a note to his son, Presley Neville, in Pittsburgh with instructions to bring the militia immediately to help defend Bower Hill.![]()

A LITTLE HORSE TRADING

At the end of the American Revolution in 1783, the thirteen states and the Congress owed money to foreign governments, such as France, that had helped finance the war, as well as to a host of Americans who had sold horses, provisions, and other supplies to the Continental Army. Initially, each state struggled to meet its financial obligations on its own, but by 1790 it was evident that servicing the debt was crippling local economies. Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton proposed that the federal government make itself responsible for the states’ debts. If consolidated with the national debt, they would total $80 million (approximately $1.820 billion in modern money).

To pay off the enormous liability, Hamilton insisted that taxes would have to rise. Hamilton’s political adversary, Thomas Jefferson, was an inveterate opponent of taxes, but he agreed to support the proposal because he recognized the need to generate income that would retire the national debt. But as a good politician, Jefferson also indulged in a little horse trading: In return for his support for Hamilton’s tax plan, Jefferson wanted Hamilton to support a proposal to relocate the national capital from Philadelphia to one of the southern states. Hamilton agreed, and they had a deal.

![]()

PRESIDENTIAL BRIEFING

(1732–1799)

• FIRST PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA (1789–97)

• BORN FEBRUARY 22, 1732, IN WESTMORELAND COUNTY, VIRGINIA

• DIED DECEMBER 14, 1799, IN MOUNT VERNON, VIRGINIA

• MEMBER OF 1ST AND 2ND CONTINENTAL CONGRESS (1774, 1775)

• PRESIDED OVER CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION IN PHILADELPHIA (1787)

• COMMANDER IN CHIEF OF CONTINENTAL ARMY (1775–83)

• ELECTED PRESIDENT 1789: FIRST ACT WAS TO URGE ADOPTION OF BILL OF RIGHTS; FEDERALIZED MILITIA TO QUELL WHISKEY REBELLION (1794)

![]()

In December 1790, Hamilton released his report on the finances of the national government. He projected that given current levels of income and expenditures—particularly now that the national government had assumed responsibility of the states’ debts—the federal budget in 1791 would see a shortfall of $826,624.73. In other words, the federal government would be more deeply in debt in 1791 than it was in 1790. If the government placed an excise tax on domestically produced spirits, however, Hamilton projected that in 1791 the government would take in $975,000, thus keeping it safely in the black.

The kind of tax Hamilton had in mind is called an excise. The word comes from an archaic term meaning inland or interior because it refers to taxes levied on goods produced within the country as opposed to taxes levied on imported foreign goods. An excise tax is collected either at the point where the product is manufactured, when it is sold to a distributor, or when it is sold to a consumer. Excise taxes had a long history in both Great Britain and America, and consumers and shopkeepers had always loathed them. In 1643, when the English Parliament placed an excise on beer and beef, mobs led by outraged butchers rioted in the streets. After the adoption of the U.S. Constitution in 1787, a group known as Anti-Federalists, political watchdogs who feared the new federal government would overwhelm state and local governments and infringe on the liberties of the people, predicted that American voters would regret the day they had ratified a Constitution that gave the national government the power to assess and collect excise taxes.

The idea of taxing whiskey made President George Washington uneasy. He did not argue against the fundamental premise that the federal government must find ways to generate more revenue, but he worried that the independent, often volatile, people of the backcountry might refuse to pay an excise on whiskey. In order to get a sense of how the ordinary American voter would receive the tax, in the spring of 1791, Washington made a tour through western Virginia and western Pennsylvania, areas with large populations of frontiersmen. Unfortunately, the president did not penetrate very deeply into the backwoods, and the local government officials he met, naturally wanting to please the great war hero, assured the former general that once the necessity of the excise was explained to the people, they would pay it. Once Washington was back in Philadelphia, he went to Congress and persuaded the members to modify the excise legislation so that whiskey distillers could pay their tax in monthly installments rather than in one lump sum. Congress passed the legislation in 1791.

![]()

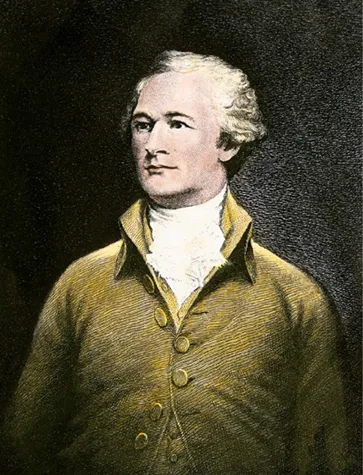

AS SECRETARY OF THE TREASURY, ALEXANDER HAMILTON WAS DETERMINED TO PUT THE UNITED STATES ON A SOUND FINANCIAL BASIS. AS A STAUNCH FEDERALIST, HE INSISTED THAT THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT HAD THE POWER TO COMPEL UNRULY BACKWOODSMEN TO PAY THEIR TAXES.

![]()

“UTOPIAN SCHEMES”

In the summer of 1791, Robert Johnson had taken the job as the federal government’s collector of the whiskey excise in Allegheny and Washington counties in western Pennsylvania. Johnson probably expected that he would not be a welcome visitor at many backcountry cabins, yet because he did not expect any serious trouble, when he went out to collect the tax money he rode alone.

On September 11, 1791, Johnson was at Pigeon Creek near Canonsburg in Washington County when eleven men dressed as women stepped out of the woods and surrounded him. It took all of the tax collector’s courage not to panic when he saw the cauldron of hot tar and the sack of feathers. The men stripped Johnson naked, hacked off his hair, then tarred and feathered him. This grotesque form of mob justice involved pouring or painting hot tar on the victim’s body, then dumping or rolling him in chicken feathers. The tar burned the skin, and it took days to peel it all off. When the men were finished, they took Johnson’s horse and left him in the woods.

In spite of the mens’ disguises, Johnson recognized two of his attackers. Once Johnson had recovered, he swore out complaints before a judge who issued arrest warrants for the suspects. In light of what had happened to Johnson, the deputy marshal was reluctant to serve the warrants himself; instead, he hired a cattle drover named John Connor to deliver the warrants. The gang that had attacked Johnson ambushed Connor, stripped him, flogged him, and tarred and feathered him. After pocketing Connor’s money and taking his horse, the culprits left him tied to a tree in the forest where he passed five long hours screaming for help before some passerby wandered within earshot and came to his rescue.

That was enough for Johnson. He published a notice in the Pittsburgh Gazette that read, “Finding the opposition to the revenue law more violent than I expected … I think it my duty and do resign my commission.”

Many settlers in the backcountry regarded the tax on whiskey as the last straw. For a century, they had petitioned the colonial and then the state legislatures for garrisons to protect them from the Indians and for surveyors to establish clear, legal boundaries on their land. The settlers had asked for fair play so that all of the best land would not go to land speculators back East, and they had asked for construction of roads and canals so they could get their produce to market. Invariably their petitions were ignored or rejected. During the Revolution, the frontiersmen tried a new tack, petitioning for independence, reasoning that as separate states they could form a government that would respond to their needs. The Continental Congress rejected this appeal, too, as the work of troublemakers and anarchists. John Adams dismissed such a petition from settlers in Kentucky as so many “utopian schemes.”

Against this backdrop, the hostile reaction of the farmers in western Pennsylvania becomes comprehensible. Most of them were scraping by on farms of a hundred acres or less. Very few of these farms were anywhere near roads or navigable rivers that could take their grain crops to the markets of Philadelphia. Those farms that were near roads or rivers could not afford the freight charges that ranged from $5 to $10 per hundred pounds of grain. The farmers had found, however, that by distilling their grain into whiskey, they could load two eight-gallon kegs on a horse and walk to Philadelphia, where backcountry liquor sold for $1 a gallon. Now the federal government wanted them to pay a tax of ten cents on each gallon of whiskey they distilled.

Yet large distillers were taxed at a lower rate, and they could pass the cost of the excise tax on to their customers. The backwoods distillers could not easily push the added cost onto their neighboring customers, however, for they, too, were mostly cash-poor farmers and laborers. Because the frontier farmers kept a large percentage of the whiskey they distilled for their own consumption and used the surplus to barter for other goods, they felt that a disproportionate share of the tax burden was falling upon them.

They had a point. In New Hampshire, for example, where scarcely anyone had a still, the whiskey tax would have virtually no impact. But in western Pennsylvania, at least one farmer in five distilled his own whiskey. In 1783, when the Pennsylvania state legislature had tried to place a tax on whiskey, the westerners had forced the legislators to repeal the tax. Why should they not enjoy the same success against the federal government?

![]()

A FIRE AT BOWER HILL

By the evening of July 16, the people of the backwoods were already describing the death of Miller outside the Neville house as murder. The men who had confronted Neville that morning were joined by many others in a nighttime meeting to discuss what they ought to do next. Someone, whose name was not recorded, proposed that “a sum of money [should] be raised and given to some ordinary persons to lie in wait and privately take the life of General Neville.” This was voted down, but there was agreement to march on Neville’s house again the next day and avenge Miller’s death. Exactly how they would take their revenge was not specified.

Neville’s appeal for men from the local militia to come help him defend his home was declined, but Major James Kirkpatrick and ten soldiers from nearby Fort Pitt volunteered to help defend Bower Hill. The troops were joined there by the general’s son, Presley Neville, who, as expected, would fight for his home.

At 5 P.M the next day, July 17, between 500 and 700 frontiersmen, marching to the sound of drums, assembled before Bower Hill. John Neville was not there to see it because Major Kirkpatrick had already smuggled him out of the house and told him to lie low in a heavily forested ravine. The frontiersmen’s new captain was James McFarlane, a former lieutenant in the American Revolution. Stepping forward under a flag of truce, McFarlane commanded Neville to come out and surrender the tax records. Kirkpatrick replied that Neville was not at home, but said he would permit six of McFarlane’s men to search the house and confiscate whatever official documents they liked.

That was not good enough for McFarlane. He insisted that Kirkpatrick and the soldiers from Fort Pitt come out and lay down their arms. Kirkpatrick refused, saying he could see plainly that McFarlane and his men planned to destroy the Neville family’s property. After this exchange, the frontiersmen surrounded the house, then set fire to a barn and one of the slave cabins. McFarlane made one final offer: He would give safe conduct to Mrs. Neville “and any other female part of the family” who wished to leave the house. Kirkpatrick accepted this offer, and the women of the house evacuated. Once the women were a safe distance from Bower Hill, the frontiersmen opened fire.

For more than an hour, the defenders and the frontiersmen blasted away at one another. Then McFarlane believed he heard someone inside the house call to him. He ordered his men to hold their fire, and, expecting that Major Kirkpatrick or Presley Neville was ready to agree to terms, he stepped out from behind the tree where he had taken cover during the gun battle. Several shots rang out from the house, and McFarlane fell dead.

To the frontiersmen, it appeared to have been a cowardly trick, and they avenged their captain by setting fire to the other barns and outbuildings of the Neville estate. The men inside Bower Hill fought on, but when the frontiersmen set fire to the kitchen beside the house, Kirkpatrick and Presley Neville knew the house was doomed. They surrendered.

No precise casualty list exists for the fight at Bower Hill. Three or four of Kirkpatrick’s soldiers were wounded, and one of them may have died later. One or two frontiersmen, along with McFarlane, died, but there is no record of how many were wounded, nor if any of these wounded died of their injuries. Kirkpatrick and Presley Neville were manhandled by their captors, but they were not injured. Meanwhile, Bower Hill, General Neville’s estate, burned to the ground.

As for McFarlane, his friends gave him a martyr’s funeral. The headstone erected over his grave read: “He departed this life July 17, 1794, aged forty-five. He served through the war, with undaunted courage in defense of American independence, against the lawless and despotic encroachments of Great Britain. He fell at last by the hands of an unprincipled villain in support of what he supposed to be the rights of his country, much lamented by a numerous and respectable circle of acquaintances.”

![]()

HOW WHISKEY SAVED PITTSBURGH

Five days after the burn...