![]()

PART I

From the Mountains to the Prairies

![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Cross-Section of America

The West Shore Railroad special chugged along the banks of the Hudson River. The run from Weehawken, New Jersey, through New York City and Albany, and finally west to Buffalo, was routine. This morning, however, the train was scheduled to stop at West Point, where many of its passengers would gather up their belongings and step off the train into a new life.

In June 1911, the United States Military Academy was in its 109th year. For more than a century, young men had come there to learn the arts of military command and bearing. The curriculum consisted of such courses as civil and military engineering, ordnance and science of gunnery, law, Spanish, drill regulations (Hippology), natural and experimental philosophy, chemistry-mineralogy-geology, drawing, and drill regulations (cavalry and artillery).

The academic experience at the Academy had changed little since Sylvanus Thayer, a career US Army officer who served as superintendent from 1817 to 1833 and came to be known as the “Father of West Point,” had emphasized engineering and thus elevated the institution to one of the foremost colleges for that discipline in America. Steeped in tradition, West Point had produced officers for the US Army since 1802, when its first class, consisting of two young lieutenants, had graduated. It had endured a horrific civil war that had ended less than half a century earlier as its progeny held the highest of command responsibilities in both the Union and Confederate armies. It had borne the ebb and flow of financial shortfall, the wax and wane of political indifference, and the decline of its rudimentary facilities.

Still, West Point maintained a command presence as imposing as its spit and polish graduates. Its stern, gray edifice was a fortress guarding tradition and seemed to whisper the motto of “Duty, Honor, Country” that would be ingrained in the psyche of every second lieutenant who left its hallowed grounds with a commission in the United States Army.

Although the sun was not yet full in the sky, the heat weighed on the shoulders of the young men who spilled from the train onto the platform, milling around. They sized up one another, they stared at the dark Gothic fortress that crowned a nearby hill, and then they began the dusty walk up the steep dirt road toward the top of that hill and the wide plain that featured a spectacular view of the Hudson River Valley below.

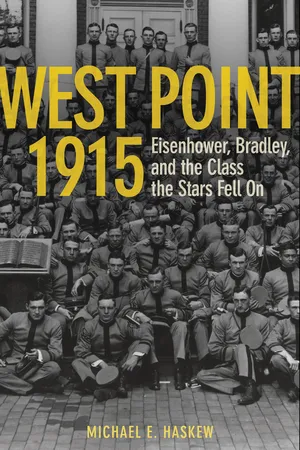

The young men of the West Point class of 1915 left their civilian lives along that road. Few if any of these men, most of them in their late teens, grasped the magnitude of the journey they were beginning. By the time all 287 of them arrived, they were the largest plebe class to have entered the Academy. By graduation, their ranks had thinned to 164, the largest number of graduates in Academy history up to that point. The attrition rate of more than 40 percent is mute testimony to the rigors of life at West Point.

Among those who persevered, stood the tests, and reached graduation day in 1915 were soldiers whose careers would shape the military and political future of the United States and indeed the world for more than half a century. It included soldiers who would die young and soldiers who would leave varied legacies for better or worse. These were the soldiers of the Class the Stars Fell On. Fifty-nine of those who received commissions on June 12, 1915, would earn at least the rank of brigadier general, an unprecedented number in American history.

They came to West Point from forty-six states and territories, the Panama Canal Zone, and the Philippine Islands. They hailed from big cities, small towns, the mountains, and the prairies, each with their own motivation and heretofore limited perspective on the world. They were rich and poor, privileged, and working class.

One of the prospective plebes trudging up the hill that day was Dwight David Eisenhower of Abilene, Kansas. Taller than most of the others, and slightly older at twenty, the thoughtful new cadet had been lured eastward by a free education, paid for by the American taxpayer. He learned soon enough that that education was anything but free.

Muscular, with light blond hair and blue eyes, Dwight was born the third of seven sons on October 14, 1890, in Denison, Texas, to David and Ida Eisenhower. His father had moved the family south from Dickinson County, Kansas, to take a job cleaning locomotives for the Cotton Belt Railroad. With their roots in Pennsylvania, the Eisenhowers had come to the prairie in the 1870s in search of cheap farmland. Before Dwight’s second birthday, the family returned to Abilene, Kansas, where David went to work at the Belle Springs Creamery.

As Dwight grew up in Abilene, he was fascinated by stories of the city’s history. Only a few decades earlier, the town that had sprung to life along the Chisholm Trail bustled with the cattle drives, saloons, and bravado of the Old West. The boy’s imagination conjured images of cowboys, lawmen, and adventurers. It was to be a lifelong interest. He also developed into a fine football player.

The seven Eisenhower brothers managed to complete their high school educations, and Dwight worked for two years in the Belle Springs Creamery. The story goes that he flipped a coin with his brother Edgar, the winner heading to college and the loser holding on with a night engineer’s position at the creamery and sending money to the other. Edgar set out for the University of Michigan.1

Dwight worked long hours at the creamery, and on occasion his friend Everett “Swede” Hazlett Jr., whose father owned a local gas lighting store, would stop by to play cards or pass time in conversation. Years later, Eisenhower acknowledged that it was Swede who first planted the seeds of a service academy education in his mind. The two cooked up an ambitious agenda. Both would apply to the US Naval Academy at Annapolis, Maryland; the US Military Academy at West Point, New York, would be a second option.

Hazlett secured his appointment to Annapolis and served with the US Navy until a heart attack cut his career short in 1939. Recalled to active duty during World War II, he taught at the Naval Academy and then supervised the naval reserve officers training program at the University of North Carolina. Eisenhower and Swede Hazlett maintained a lifelong friendship until Hazlett died of cancer in 1958.

For Dwight, the road to West Point was something of a test in itself. He wrote a letter to Congressman Roland R. Rees, who replied that he had no appointments available. Rees did advise that Dwight contact Senator Joseph L. Bristow, who was authorized to make one appointment to each academy for 1911. The enterprising young man from the wrong side of the Abilene tracks knew no people of political influence; however, he solicited the support of prominent citizens and the town newspaper editors, asking for letters of recommendation.2

Senator Bristow was slow to respond to a letter from Eisenhower written in August 1910. Two weeks later, the impatient young man from Abilene took up his pen again.

On September 3, 1910, Dwight wrote the senator in forthright, plain-spoken language:

Dear Sir: sometime ago I wrote to you applying for an appointment to West Point or Annapolis. As yet, I have heard nothing definite from you about the matter, but I noticed in the daily papers that you would soon give a competitive examination for these appointments.

Now, if you find it impossible to give me an appointment outright, to one of these places, would I have the right to enter this competitive examination?

If so, will you please explain the conditions to be met in entering this examination, and the studies to be covered. Trusting to hear from you at your earliest convenience, I am, Respectfully yours, Dwight Eisenhower, Abilene, Kansas.3

Within the month, Eisenhower was sitting with seven other candidates in the Office of the Superintendent of Public Instruction in the state capital of Topeka, taking Senator Bristow’s examination. When asked his preference, Dwight replied that either Annapolis or West Point would be acceptable—in effect, he thought, doubling his chances for an appointment. Weeks of hard work, burning the midnight oil at the creamery with the help of Swede Hazlett, brought results.

When the scores were tallied, only George Pulsifer Jr. (who received an at-large appointment to the class of 1915, was wounded in World War I, and achieved the rank of major), scored higher. Pulsifer, however, had specified his preference for West Point, elevating Eisenhower to the top of the Annapolis list and placing him second for West Point. Bristow asked a close advisor, Phil Heath, to review all eight applications, and Heath placed Eisenhower ahead of Pulsifer for the West Point slot. Bristow chose not to appoint Eisenhower to Annapolis, naming him to the US Military Academy instead.

Eisenhower and Hazlett were disappointed that they would not be classmates, but fortuitously Eisenhower was spared an even greater disappointment. Having turned twenty in October 1910, he was actually too old to gain admission to Annapolis. He was also required to submit a letter to Bristow certifying his age in years and months and the length of his residency in the state of Kansas.

Eisenhower replied to Bristow the day after receiving the senator’s letter of appointment. On October 25, 1910, he wrote, “Your letter of the 24th instant has just been received. I wish to thank you sincerely for the favor you have shown me in appointing me to West Point.

“In regard to the information desired; I am just nineteen years and eleven days of age, and have been a resident of Abilene, Kans. for eighteen years. Thanking you again, I am very truly yours, Dwight Eisenhower.”

Curiously, Eisenhower’s twentieth birthday had passed eleven days earlier. In his August 1910 letter to Bristow, he had also stated that he would be “nineteen years of age this fall.” This was either a second inadvertent misstatement of his age or a deliberate attempt to ensure that there would be no confusion as to his eligibility for admission to West Point.4

In January 1911, the four-day West Point entrance examination took place in St. Louis, Missouri, at Jefferson Barracks on the edge of the city. Eisenhower had never been so far from home. He took the train to St. Louis, decided to see the sights, and got lost. Well after dark on his first night in the city, he snuck back into his assigned lodging. His scores on the academic and physical examinations were good enough to place him in the middle of the group of Academy hopefuls. Five months later, he boarded the train in Abilene for the long trek to West Point, with a first stop in Kansas City and then a short visit with Edgar in Michigan before making the journey’s final leg to the Academy.

When they reached the plateau above the train station, the new arrivals gained their first taste of military life. A long row of tables, each with a cadet behind it, stretched in front of the administration building. Stepping into the forming lines, each plebe was required to sign a form tersely stating that the individual agreed to serve eight years in the US Army from the date of his acceptance into the service. When asked whether or not they used tobacco, some cadets responded, “No, sir.”

In 1903, just after the observance of the Academy’s centennial, a program of renovation and construction had begun. The immense riding hall and heating plant were completed in 1909, and the Old Cadet Chapel, built in 1836, was dismantled and moved to the cemetery while a new chapel was being constructed. To the east, the unfinished academic building, with its rock-faced granite walls and limestone decoration, was rising a short distance from the cliffs.

The new arrivals had little time to take notice. In a well-choreographed and somewhat harrowing procession, they were hustled away to surrender their cash to the treasurer, as no cadet was allowed to carry currency. A cursory physical followed, and then the cadets were assigned to one of six hundred-man companies. The tallest went either to A or F Company, with the shorter cadets, or runts, in B, C, D, and E Companies. Companies A and F, known as flankers, marched on either end of the Cadet Corps formation. Classification by height maintained symmetry of uniforms and equipment in the ranks. Standing slightly taller than five feet ten inches, Eisenhower was in F Company.

From there, baggage went to storage—not to be seen again for nearly two summers, at which point the new cadets would first be eligible for leave. Some shuffled off to barracks that fronted a quadrangle, where they met their roommates for the first time and saw their new quarters.

Others double-timed to the barber shop for a regulation short haircut and then scrambled to the cadet store for their mattresses, sheets, and blankets. Then came the issue of uniforms, gray flannel trousers and tunics with assorted other garments.5

All the while, the upper classmen and yearlings—second-year cadets who had recently been on the receiving end of merciless hazing themselves—meted out loud orders along with liberal amounts of harassment. It was only the beginning. Since the 1850s, the hazing of new arrivals at West Point had risen to an art form. Tradition demanded that plebes endure the rigors of “Beast Barracks,” a wave of hazing that stripped away any arrogance or overconfidence, and along with it any vestige of civilian consciousness that lingered. The new arrivals were “Beasts,” referred to regularly as the “scum of the earth.”

By 5:00 p.m. on that whirlwind first day, the Beasts assembled in their somewhat ragged ranks. They stood at attention on the parade ground as the Corps passed in review. The sight was daunting.

Then, they swore the oath of allegiance:

I do solemnly swear that I will support the Constitution of the United States and bear true allegiance to the national government; that I will maintain and defend the sovereignty of the United States paramount to any and all allegiance, sovereignty, or fealty I may owe to any state, county or country whatsoever, and that I will at all times obey the legal orders of my superior officers and the rules and articles governing the armies of the United States.

Fourteen members of the class of 1915 were known as “Augustines.” These young men had gained appointments to West Point during the late spring of 1911 and officially entered the Academy on August 1, fully six weeks behind those who had arrived in June. The Augustines had generally gained admission due to an act of the US Congress that changed the guidelines for appointments to the service academies. Previously, legislators had been allowed only one appointment to West Point every four years. The change provided for an appointment every three years.

Among these Augustines was eighteen-year-old Omar Nelson Bradley of Moberly, Missouri. Born February 12, 1893, on a farm in rural Clark County, Omar was the son of John Smith and Sarah Elizabeth Bradley. John worked as a schoolteacher, often walking several miles a day to and from home to teach in one-room schoolhouses around the town of Higbee, usually with his son in attendance. Omar, an excellent student, remembered his father as an outstanding marksman and hunter who taught him not only to love books and learning but also to appreciate the outdoors and sports—particularly baseball.

In January 1908, John Bradley died of pneumonia at the age of forty-one. Omar was a few days shy of his fifteenth birthday. Within months, his mother, known as Bessie, decided to relocate to Moberly, about fifteen miles from Higbee. Omar attended the local high school and delivered the newspaper, the Moberly Democrat, to earn a little money to supplement his mother’s income as a seamstress along with the rent she received from taking in boarders.

After graduating from high school in the spring of 1910, Omar remained concerned for his mother’s financial welfare. He worked for the Wabash Railroad in the supply department and as a boiler repairman, hoping to save enough money during the course of a year to enroll at the University of Missouri in Columbia. He intended to continue working, finding another job in Columbia while pursuing a law degree. By the end of the year, however, his mother had remarried. The path to Columbia seemed wide open.

Abruptly, however, the young man’s plan took a major detour.

During a conversation, John Cruson, the Sunday school superintendent at Central Christian Church, where the Bradleys worshipped, suggested that Omar seek an appointment to West Point instead. When Omar responded that he could not possibly afford such an educational opportunity, Cruson explained that the expenses were paid by the government.

“He put me straight,” Bradley remembered years later. “He told me that not only was West Point free, but that the cadets were paid a small monthly salary while there. He went on to explain how one got an appointment through one’s congressman, competing against other candidates.”6

When Omar wrote to Congressman William M. Rucker requesting an appointment, he wa...