eBook - ePub

Available until 9 Feb |Learn more

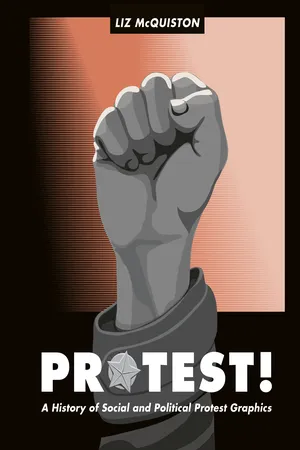

Protest!

A History of Social and Political Protest Graphics

This book is available to read until 9th February, 2026

- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 9 Feb |Learn more

About this book

Discover the power and impact of protest art with this authoritative, richly illustrated history of social and political protest graphics from around the world.

Expertly written and unique in its scope, this extraordinary book features hundreds of the best examples of posters, prints, murals, graffiti, political cartoons and other endlessly inventive graphic forms that have been used in political protest throughout history and to the present.

Spanning continents and centuries, Protest! documents the vital role of the visual arts in calling for freedom and change. It examines how graphics have been used to highlight injustice, protest wars, satirize authority figures, demand equal rights and fight for an end to discrimination.

An astounding emotional visual exploration which includes:

Hogarth’s Gin Lane, Goya’s Disasters of War, Thomas Nast’s political caricatures, French and British comics, postcards from the women’s suffrage movement, satirical anti-fascist magazines, ‘Ban the Bomb’ demonstrations, clothing of the 1960s counterculture, Cuban revolutionary poster art, the anti-apartheid illustrated book How to Commit Suicide in South Africa, the “Silence=Death” emblem from the AIDS crisis, The Last Whole Earth Catalog, anti-corporate advertising campaigns, Stonewall posters and postcards, murals created during the Arab Spring, electronic graphics from Hong Kong’s Umbrella Revolution, posters created for the Women’s March, the Trump Baby inflatable blimp, the magazine Charlie Hebdo, Black Lives Matter posters and flags.

Expertly written and unique in its scope, this extraordinary book features hundreds of the best examples of posters, prints, murals, graffiti, political cartoons and other endlessly inventive graphic forms that have been used in political protest throughout history and to the present.

Spanning continents and centuries, Protest! documents the vital role of the visual arts in calling for freedom and change. It examines how graphics have been used to highlight injustice, protest wars, satirize authority figures, demand equal rights and fight for an end to discrimination.

An astounding emotional visual exploration which includes:

Hogarth’s Gin Lane, Goya’s Disasters of War, Thomas Nast’s political caricatures, French and British comics, postcards from the women’s suffrage movement, satirical anti-fascist magazines, ‘Ban the Bomb’ demonstrations, clothing of the 1960s counterculture, Cuban revolutionary poster art, the anti-apartheid illustrated book How to Commit Suicide in South Africa, the “Silence=Death” emblem from the AIDS crisis, The Last Whole Earth Catalog, anti-corporate advertising campaigns, Stonewall posters and postcards, murals created during the Arab Spring, electronic graphics from Hong Kong’s Umbrella Revolution, posters created for the Women’s March, the Trump Baby inflatable blimp, the magazine Charlie Hebdo, Black Lives Matter posters and flags.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Protest! by Liz McQuiston in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

1500–1900

Early Developments: The Reformation and Social Comment

If searching for early examples of visual defiance against authority, it is tempting to use the beginning of the 20th century as a starting point. After all, that century defines an era, more or less, of living memory (ours or our relatives), and the centuries before that seem too vast and too distant. The vastness is true: disputes and protests and their visual expression, stretch far back in time, and are of such quantity as to offer a whole study in itself. But the distance, conceptually speaking, is false. Even a superficial glance at those earlier centuries is startling, for many of the issues at the centre of the protests, as well as the way that artists communicated them, are surprisingly similar to those of the present.

This chapter therefore deals with the vastness of the pre-1900s by presenting particular highlights of graphic work, and their creators, over those earlier centuries. The Protestant Reformation provides a good starting point. The advent of the ‘political print’, as a tool of protest, relied heavily on the multiplication of an image as a means of spreading its anger. Both paper and print had become available to the West in the 1400s. By the early 1500s, printing allowed an image to be multiplied, important in spreading ideas to the illiterate masses. It was possible to show anger towards life’s injustices or those in power, by producing crude or awful depictions of key people or actions, then reproducing them in multiples and distributing them by means of strolling printsellers. Thus such messages were carried mainly through pictures (as few could actually read).1

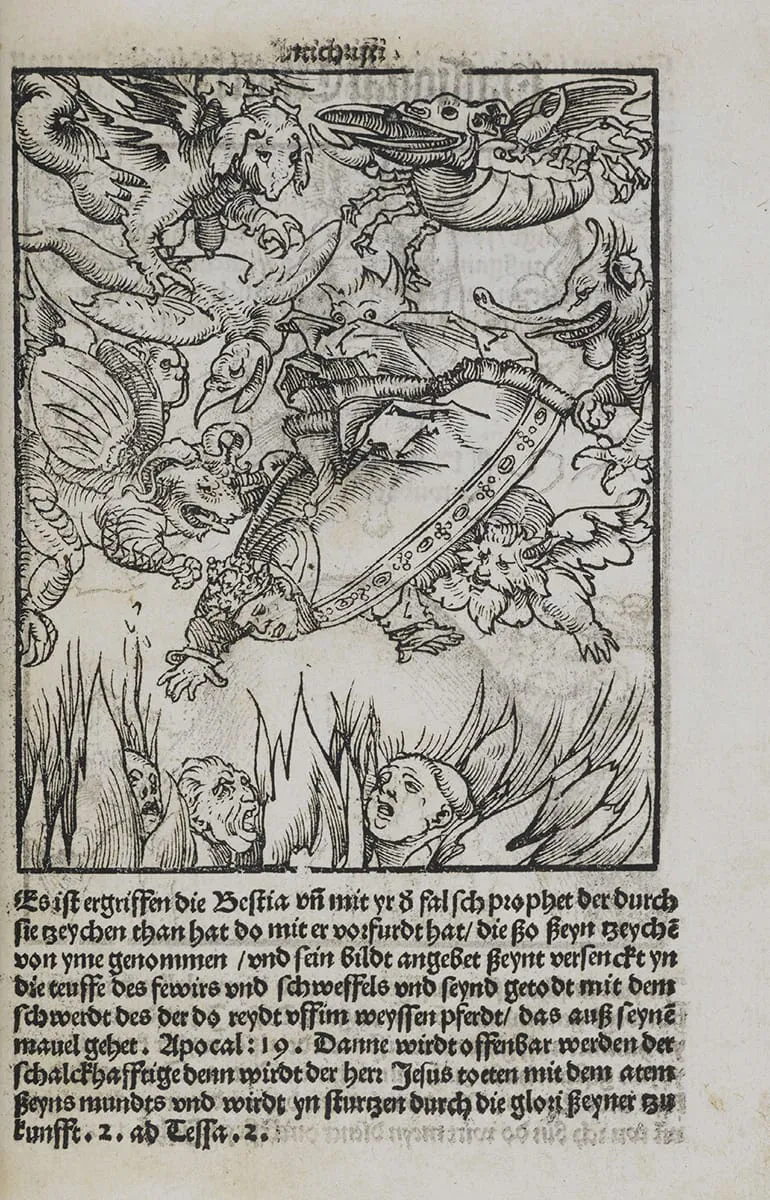

The first great movement of resistance was aimed at the power of the Catholic Church and the authority of its Pope. It came in the form of Martin Luther’s Reformation, ignited in 1517 by his posting of his Ninety-Five Theological Theses on the door of the church in Wittenberg. Illustrations became one of the Reformation’s most productive forces of propaganda and communication. Many of the German artists at that time were against Rome, particularly those close to Luther such as his friend Lucas Cranach the Elder, as well as Mathias Grünewald, Albrecht Dürer and others. The artwork, artistically, tended to be extremely aggressive and crude. Messages tended to be simple, direct and devoid of broader arguments or ethical discussion. Unlike books, which were largely appreciated by a small, intellectual set of the population, prints were for the masses – and often oppositional, showing anger, demanding justice or applying cruel humour to the controllers above them.2

‘The Miseries and Misfortunes of War’ (1632–33), by Jacques Callot (1593–1635), is often experienced through the display of only one of its most distressing images, entitled ‘The Hanging Tree’. It is in fact a morality tale, told in a sequence of 18 small etchings, each measuring roughly 8.1 cm high by 18.6 cm wide (3.5 × 7.5 in). It is considered to be one of the first attempts to show how the horrors of war impact on the very fabric of society, particularly the common people. But it is also a tale about the notion of ‘going to war’: what happens to those who are recruited, transformed by the insanity of battle, and then run berserk, killing and maiming innocents and committing atrocities. The recruits then suffer gruesome punishment by their commanding officers (who catch up with them), and even worse, by peasants seeking to avenge the innocents.3

The Pope Descending to Hell 1521

Lucas Cranach the Elder

Lucas Cranach the Elder

Callot was born in the Duchy of Lorraine, apparently of noble birth. Throughout much of his life, he was known to enjoy and keep company with the poorer sectors of society as well as with the rich and powerful. The latter would have been necessary as etching was an expensive process and he would have been in need of a patron or two along the way. The French army invaded Lorraine in 1633, wreaking havoc and carnage on a grand scale, and therefore providing the backdrop against which ‘The Miseries’ were created, and must be read.4

Our modern spirit of revolution, embedded in the smallest protest or uprising, has often mythologized or claimed its historical roots in the French Revolution of 1789. The French Revolution desired and manifested earth-shattering changes. It produced the ‘Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen’, presenting the new and crucially democratic idea that ‘the state’ was not the property of a king or royal dynasty, but was composed of its people, thereby giving birth to the idea of ‘nationhood’. (For men only; unfortunately the revolution had no interest in giving political rights to women.) In January 1793 King Louis was guillotined, and later in the year so was his wife Marie Antoinette. Hence the revolution also produced bloodshed: harsh divisions formed between the revolutionaries (Jacobins) and the moderates (Girondins). The Jacobins seized power and the Committee of Public Safety, headed by the overly fastidious Robespierre, began ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- 1 Early Developments: The Reformation and Social Comment (1500–1900)

- 2 Constructing a New Society (1900–1930)

- 3 Fascism, The Cold War and The Bomb (1930–1960)

- 4 Redirection and Change (1960–1980)

- 5 The AIDS Crisis and Other Global Tensions (1980–2000)

- 6 Revolutions and the Demand for Rights (2000–Present)

- Endnotes

- Bibliography

- Index

- Picture credits

- Acknowledgements

- Copyright