1 Steam Underground

The Circle line platforms at Baker Street, restored in the 1980s to an approximation of their original 1860s appearance.

The same platforms as they appeared in 1863.

A London Pioneer

Proposals to build the world’s first underground railway came out of the search for a solution to London’s growing traffic problems and the congestion on its streets. By the mid-nineteenth century, Britain’s capital was the largest and most prosperous city in the world. Its success as a port and commercial centre, based on Britain’s rapidly growing empire, led to an unprecedented explosion in the city’s population.

This rose from just under 1 million at the first census in 1801 to more than 2.5 million fifty years later, when the Great Exhibition of 1851 provided London’s first major tourist attraction in Joseph Paxton’s Crystal Palace. Most of the many thousands of visitors from out of town, whether from elsewhere in Britain or from overseas, arrived in London at a main-line station and then had to walk or fight for a seat on an omnibus in order to reach Hyde Park. There were no railways across the capital, and only the Great Western Railway (GWR) terminus at Paddington, through which visitors from the west of England arrived, was close to the park.

The unprecedented crowds that thronged to the Great Exhibition highlighted for the first time a pressing issue of which Londoners and regular visitors were well aware. Improved communications and transport within and across the metropolis were becoming essential to unlock the impossible congestion on the city’s main thoroughfares, where people, horses, carts, wagons, cabs, omnibuses and livestock being driven to market could bring the streets to a virtual standstill.

Balloon view of London from the south-east, c.1840. The London and Greenwich Railway (LG&R), the capital’s first passenger railway, is shown lower right, approaching its London Bridge terminus on brick arches, which are still in use today.

The first main-line railways established separate London termini at London Bridge (1836), Euston (1837), Paddington (1838), Shoreditch (1840) and Fenchurch Street (1841). There were many more railway promotions in the ‘railway mania’ of the 1840s, when the House of Commons had to consider 435 railway bills for England and Wales. These were all private enterprise schemes in which the government had no direct involvement, but every project had to be scrutinized and authorized by Parliament. This ‘light touch’ state regulation was standard procedure in Victorian Britain and could both delay and frustrate major infrastructure projects. A Royal Commission on London termini was established in 1846 to consider the particular problem of railways entering the City and Westminster, and immediately answered its own question by defining a central railway-free zone. At this stage, only one small terminus, Fenchurch Street, had opened within the ‘square mile’ of the City of London and none of the lines from the south had bridged the river. Even so, the existing railways on the edge of London were contributing to the congestion at the centre, and rail companies without a direct connection to the business centre were pushing to get access for themselves. Eventually, the number of rail termini in London rose to fifteen by the end of the nineteenth century, more than any other city in the world. The idea of a single, giant Hauptbahnhof (central station) to accommodate all main lines to a city, as later developed in Germany, was never seriously considered for London and would probably never have been agreed between the competing private railway companies.

However, back in the 1840s and 1850s, both Parliament and the City Corporation were determined to keep central London free of railways and, as one historian neatly put it, ‘hold back the London termini at an invisible ring wall’. This ruling was not an absolute embargo but it was a strong recommendation to Select Committees considering future railway bills. In fact, promoters were already discouraged by the high costs of acquiring land and demolishing property, and by the actions taken by the landed aristocracy to preserve the integrity of their central London estates. In 1855, another Parliamentary Select Committee on Metropolitan Communications recommended, as a potential solution, that the existing and future main-line termini in London should be linked by an underground railway, but offered no detail as to how this might be achieved.

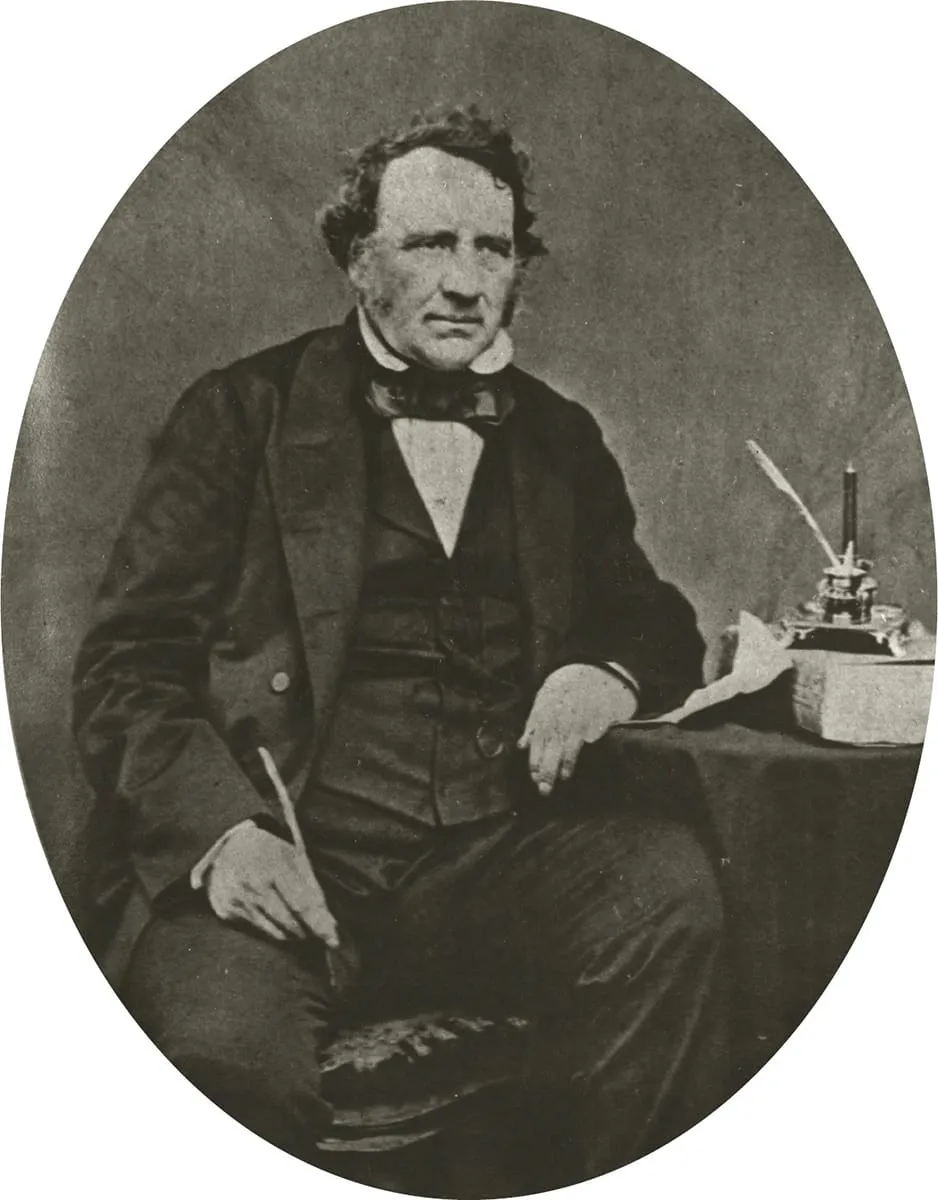

The idea was not new, having first been suggested in the 1830s. One of its earliest advocates was the City Corporation’s solicitor Charles Pearson. He was an unusually forward-thinking man who could see both economic and social benefits to linking the main-line railways with the City. Pearson proposed a railway with up to eight tracks running in a covered way under a broad new road down the Fleet valley from King’s Cross to a large goods and passenger terminal at Farringdon. This was to form part of an existing improvement scheme to clear the insanitary slum areas of Clerkenwell. The displaced inhabitants, Pearson suggested, could move out to healthier suburbs and be offered cheap fares for a daily train journey to work in the centre of town.

Charles Pearson, the City Corporation’s solicitor, c.1860.

It was an appealing but idealistic vision that not surprisingly failed to attract investors, although cheap workmen’s fares were later put in place by Parliament as a way to force railway companies to provide some social compensation for their urban projects. The City Terminus Company was formed in 1852 to pursue Pearson’s scheme, but neither the City Corporation nor the main-line companies showed any enthusiasm for funding it.

A separate, more commercially motivated underground venture, originally known as the Bayswater, Paddington & Holborn Bridge Railway, was proposed at this time. Unlike Pearson’s scheme, this did not involve expensive property demolition or costly road building, but would be routed mainly below the New Road between King’s Cross and Paddington, running very close to a third main-line station at Euston on...