- 912 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The blacksmith’s ABCs—learn metalworking as taught by the old masters!

The forging of metal gave birth to the Iron Age, and Practical Blacksmithing is the classic primer on the craft that shaped modern civilization. Featuring more than 1,000 illustrations, this foundational text describes every aspect of working with iron and steel, and is essential for both the do-it-yourself backyard blacksmith and the professional metalworker.

Originally published in four volumes in the early 20th century, this hefty, single-volume, new edition of Practical Blacksmithing is different from similar books in that it includes contributions by working tradesmen. In addition to its clear and concise instructional material, the book’s editor collected the actual words of old-time blacksmiths offering their best methods, unique how-tos, original techniques, and arcane knowledge.

Industrialization and mass production may have led to the disappearance of the blacksmith from everyday life, but the art of metalwork never died. It smoldered like hot coals in a forge, and today those coals are red hot as craftsman taking up blacksmithing as a hobby or art form seek to learn the foundational aspects of the trade.

Proving that what may be old can actually be new and useful, Practical Blacksmithingdescribes all the important smithing processes: welding, brazing, soldering, cutting, bending, setting, tempering, fullering and swaging, forging, and drilling. It also includes the early history of blacksmithing and describes tools used since ancient times. In addition to thousands of other useful facts, the modern blacksmith will be introduced to old tools and learn how to make them, and can even learn how to build a retro blacksmith shop with detailed do-it-yourself plans!

The forging of metal gave birth to the Iron Age, and Practical Blacksmithing is the classic primer on the craft that shaped modern civilization. Featuring more than 1,000 illustrations, this foundational text describes every aspect of working with iron and steel, and is essential for both the do-it-yourself backyard blacksmith and the professional metalworker.

Originally published in four volumes in the early 20th century, this hefty, single-volume, new edition of Practical Blacksmithing is different from similar books in that it includes contributions by working tradesmen. In addition to its clear and concise instructional material, the book’s editor collected the actual words of old-time blacksmiths offering their best methods, unique how-tos, original techniques, and arcane knowledge.

Industrialization and mass production may have led to the disappearance of the blacksmith from everyday life, but the art of metalwork never died. It smoldered like hot coals in a forge, and today those coals are red hot as craftsman taking up blacksmithing as a hobby or art form seek to learn the foundational aspects of the trade.

Proving that what may be old can actually be new and useful, Practical Blacksmithingdescribes all the important smithing processes: welding, brazing, soldering, cutting, bending, setting, tempering, fullering and swaging, forging, and drilling. It also includes the early history of blacksmithing and describes tools used since ancient times. In addition to thousands of other useful facts, the modern blacksmith will be introduced to old tools and learn how to make them, and can even learn how to build a retro blacksmith shop with detailed do-it-yourself plans!

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Practical Blacksmithing by M. T. Richardson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Technical & Manufacturing Trades. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

VOLUME I

PREFACE

Although there are numerous legendary accounts of the important position occupied by the blacksmith, and the honors accorded him even at a period as remote in the world’s history as the time of King Solomon, strange to relate there is no single work in the language devoted solely to the practice of the blacksmith’s art. Occasional chapters on the subject may be found, however, in mechanical books, as well as brief essays in encyclopedias. While fragmentary allusions to this important trade have from time to time appeared in newspapers and magazines, no one has ever attempted anything like an exhaustive work on the subject; perhaps none is possible. This paucity of literature concerning a branch of the mechanic arts, without which other trades would cease to exist from lack of proper tools, cannot be attributed to a want of intelligence on the part of the disciples of Vulcan. It is perfectly safe to assert, that in this respect blacksmiths can hold their own with mechanics in any other branch of industry. From their ranks have sprung many distinguished men. Among the number may be mentioned Elihu Burritt, known far and wide as the “learned blacksmith.” The Rev. Robt. Colyer, pastor of the leading Unitarian Church in New York City, started in life as a blacksmith, and while laboring at the forge, began the studies which have since made him famous.

Exactly why no attempt has ever been made to write a book on blacksmithing, it would be difficult to explain. It is not contended that in the following pages anything like a complete consideration of the subject will be undertaken. For the most part the matter has been taken from the columns of The Blacksmith and Wheelwright, to which it was contributed by practical men from all parts of the American continent. The Blacksmith and Wheelwright, it may be observed, is at present the only journal in the world which makes the art of blacksmithing an essential feature.

In the nature of things, the most that can be done by the editor and compiler of these fragmentary articles, is to group the different subjects together and present them with as much system as possible. The editor does not hold himself responsible for the subject matter, or the treatment which each tool receives at the hands of its author. There may be, sometimes, a better way of doing a job of work than the one described herein, but it is believed that the average blacksmith may obtan much information from these pages, even if occasionally some of the methods given are inferior to those with which he is familiar. The editor has endeavored, so far as possible, to preserve the exact language of each contributor.

While a skillful blacksmith of extended experience, with a turn for literature, might be able to write a book arranged more systematically, and possibly treating of more subjects, certain it is that no one up to the present time has ever made the attempt, and it is doubtful if such a work would contain the same variety of practical information that will be found in these pages, formed of contributions from hundreds of able workmen scattered over a wide area.

THE EDITOR.

CHAPTER I

ANCIENT AND MODERN HAMMERS

A trite proverb and one quite frequently quoted in modern mechanical literature is, “By the hammer and hand all the arts do stand.” These few words sum up a great deal of information concerning elementary mechanics. If we examine some of the more elaborate arts of modern times, or give attention to pursuits in which complicated mechanism is employed, we may at first be impressed that however correct this expression may have been in the past, it is not applicable to the present day. But if we pursue our investigations far enough, and trace the progress of the industry under consideration, whatever may be its nature, back to its origin, we find sooner or later that both hammer and hand have had everything to do with establishing and maintaining it. If we investigate textile fabrics, for instance, we find they are the products of looms. In the construction of the looms the hammer was used to a certain extent, but back of them there were other machines of varying degrees of excellence, in which the hammer played a still more important part, until finally we reach a point where the hammer and hand laid the very foundation of the industry.

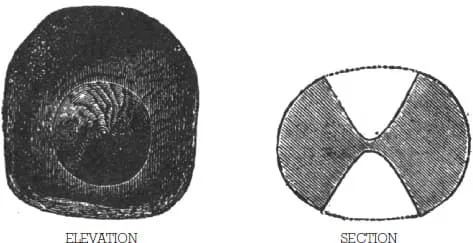

FIG. 1—A TAPPING HAMMER OF STONE

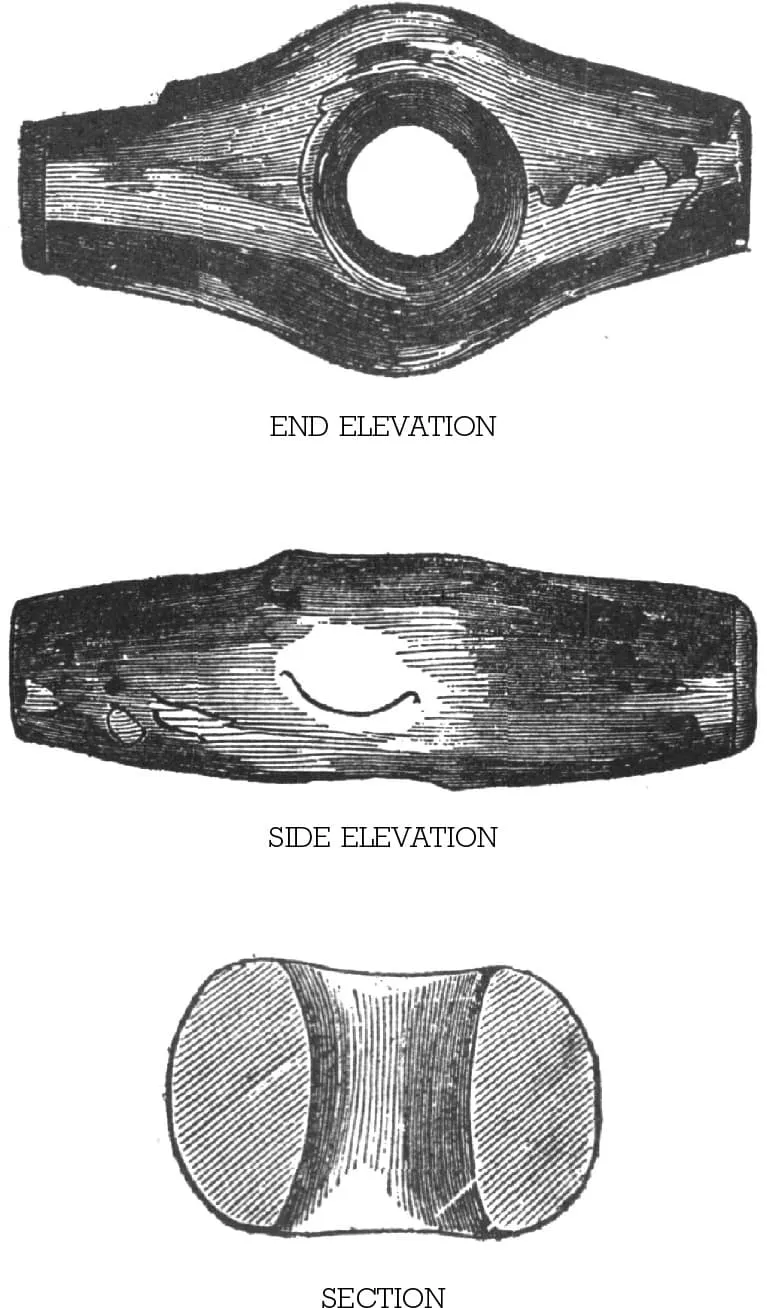

FIG. 2—PERFORATED HAMMER HEAD OF STONE

It would be necessary to go back to this point in order to start anew in case by some unaccountable means our present equipment of machinery should be blotted out of existence. The wonderful mechanism of modern shoe factories, for another example, has superseded the cobbler’s hammer, but on the other hand the hammer and hand by slow degrees through various stages produced the machinery upon which we at present depend for our footwear. And so it is in whatever direction we turn. The hammer in the hands of man is discovered to be at the bottom of all the arts and trades, if we but go back far enough in our investigation. From an inquiry of this kind the dignity and importance of the smith’s art is at once apparent. While others besides him use hammers, it is to the smith that they all must go for their hammers. The smith, among all mechanics, enjoys the distinction of producing his own tools. A consideration of hammers, therefore, both ancient and modern, becomes a matter of special interest to blacksmiths of the present day as well as to artisans generally.

The prototype of the hammer is found in the clinched fist, a tool or weapon, as determined by circumstances and conditions, that man early learned to use, and which through all the generations he has found extremely useful. The fist, considered as a hammer, is one of the three tools for external use with which man is provided by nature, the other two being a compound vise, and a scratching or scraping tool, both of which are also in the hand. From using the hand as a hammer our early inventors must have derived the idea of artificial hammers, tools which should be serviceable where the fist was insufficient. From noting the action of the muscles of the hand the first idea of a vise must have been obtained, while by similar reasoning all our scraping and scratching tools, our planes and files, our rasps, and, perhaps, also some of our edged tools, were first suggested by the finger nails. Upon a substance softer than itself the fist can deal an appreciable blow, but upon a substance harder than itself the reaction transfers the blow to the flesh and the blood of nature’s hammer, much to the discomfort of the one using it. After a few experiments of this kind, it is reasonable to suppose that the primitive man conceived the idea of reinforcing the hand by some hard substance. At the outset he probably grasped a rounded stone, and this made quite a serviceable tool for the limited purposes of the time. His arm became the handle, while his fingers were the means of attaching the hammer to the handle. Among the relics of the past, coming from ages of which there is no written history, and in time long preceding the known use of metals, are certain rounded stones, shaped, it is supposed, by the action of the water, and of such a form as to fit the hand. These stones are known to antiquarians by the name of “mauls,” and were, undoubtedly, the hammers of our prehistoric ancestors. Certain variations in this form of hammer are also found. For that tapping action which in our minor wants is often more requisite than blows, a stone specially prepared for this somewhat delicate operation was employed, an illustration of which is shown in Fig. 1. A stone of this kind would, of course, be much lighter than the “maul” already described. The tapping hammer, a name appropriate to the device, was held between the finger and the thumb, the cavities at the sides being for the convenience of holding it. The original from which the engraving was made bears evidence of use, and shows traces of having been employed against a sharp surface.

The “maul” could not have been a very satisfactory tool even for the work it was specially calculated to perform, and the desire for something better must have been early felt. To hold a stone in the hollow of the hand and to strike an object with it so that the reaction of the blow should be mainly met by the muscular reaction of the back of the hand and the thinnest section of the wrist is not only fatiguing, but is liable to injure the delicate network of muscles found in these parts. It may have been from considerations of this sort that the double-ended mauls also found in the stone age were devised. These were held by the hand grasping the middle of the tool, and were undoubtedly a great improvement o...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Contents

- Foreword

- Introduction

- Volume I

- Preface

- I. Ancient and Modern Hammers

- II. Ancient Tools

- III. Chimneys, Forges, Fires, Shop Plans, Work Benches, Etc

- IV. Anvils and Anvil Tools

- V. Blacksmiths’ Tools

- Volume II

- Preface

- I. Iron and Steel

- II. Bolt and Rivet Clippers

- III. Chisels

- IV. Drills and Drilling

- V. Fullering and Swaging

- VI. Miscellaneous Tools

- VII. Miscellaneous Tools (Continued)

- VIII. Blacksmiths’ Shears

- IX. Emery Wheels and Grindstones

- Volume III

- Preface

- I. Blacksmiths’ Tools

- II. Wrenches

- III. Welding, Brazing, Soldering

- IV. Steel and its Uses

- V. Forging Iron

- VI. Making Chain Swivels

- VII. Plow Work

- Volume IV

- Preface

- I. Miscellaneous Carriage Irons

- II. Tires, Cutting, Bending, Welding and Setting

- III. Setting Axles. Axle Gauges. Thimble Skeins

- IV. Springs

- V. Bob Sleds

- VI. Tempering Tools

- VII. Proportions of Bolts and Nuts, Forms of Heads, Etc

- VIII. Working Steel. Welding. Case Hardening

- IX. Tables of Iron and Steel

- Index

- Copyright