eBook - ePub

B-52 Stratofortress

The Complete History of the World's Longest Serving and Best Known Bomber

- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

B-52 Stratofortress

The Complete History of the World's Longest Serving and Best Known Bomber

About this book

The B-52 is the longest serving and most versatile of the United States Air Force's combat aircraft. The Stratofortress entered active service in 1955 and is scheduled to continue as part of the air force's inventory through 2040. The jet-powered bomber was a mainstay of America's Cold War nuclear-deterrent strategy, providing air power that balanced the land and sea military forces. The massive plane also served as the launch platform for the experimental X-15 hypersonic rocket aircraft. Due to its versatility as an aircraft, the B-52 has seen combat service in all of America's military conflicts since it came on active duty: Vietnam, the first and second Gulf wars, and the War in Afghanistan.

B-52 Stratofortress also covers every aspect of the aircraft's development, manufacture, and modification. These technical details set the stage for its military service, starting with its role as a nuclear bomber in the Cold War even though only conventional weapons have been used during its combat duty. The airplane’s service in key campaigns in Vietnam is covered, followed by the quieter years after it. The B-52 returned to prominence in the Gulf Wars and Afghanistan, taking part in massive bombing campaigns in both conflicts. Finally, the book ends with the constant upgrades that will keep the B-52 an integral part of U.S. airpower for decades to come.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access B-52 Stratofortress by Bill Yenne in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

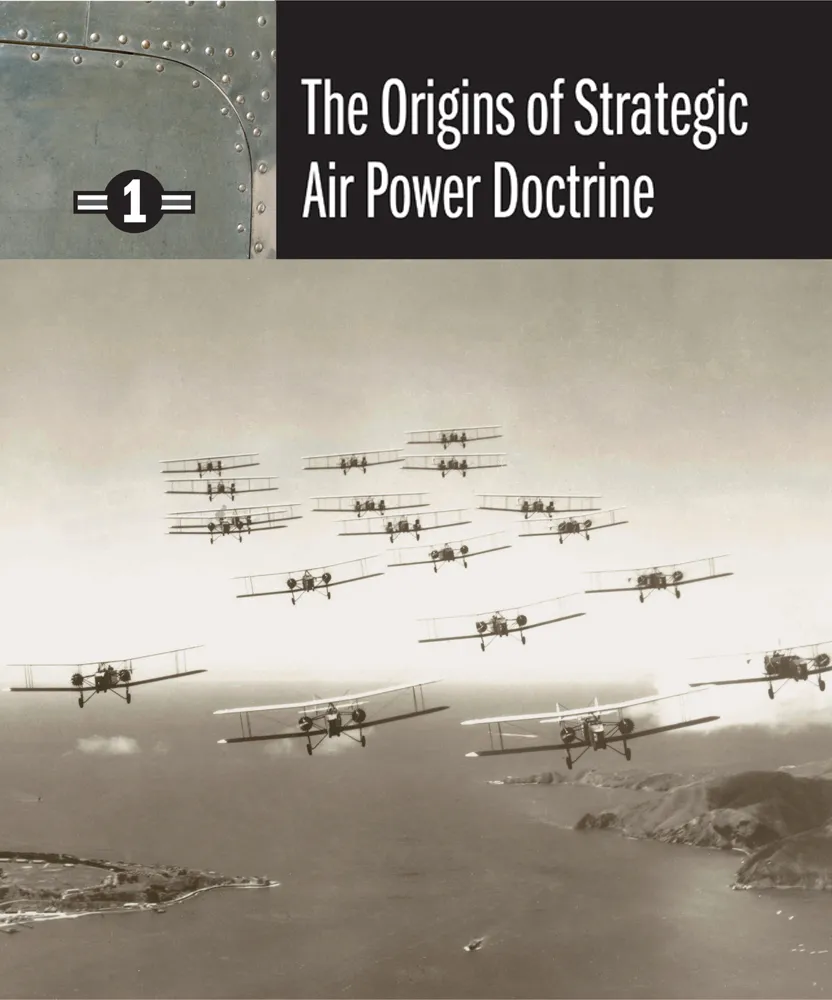

THE USE OF AIR POWER in warfare is said to date back to the first use of observation balloons by the French Aerostatic Corps at the Battle of Fleurus in 1794. During the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln became enamored with the concept and appointed balloonist Professor Thaddeus S. C. Lowe to serve as the U.S. Army’s first chief aeronaut. The Union Army used observation balloons as early as 1861 at the time of the first Battle of Bull Run. The Confederates also later used balloons.

The use of fixed-wing aircraft in wartime, both as observation platforms and to drop bombs, is believed to have had its debut during Italy’s 1911 operations in Libya against the crumbling Ottoman Empire. The technical establishment was slow to grasp the importance of such operations. In October 1910, Scientific American dismissed the idea of airplanes as war machines, noting that “outside of scouting duties, we are inclined to think that the field of usefulness of the aeroplane will be rather limited. Because of its small carrying capacity, and the necessity for its operating at great altitude, if it is to escape hostile fire, the amount of damage it will do by dropping explosives upon cities, forts, hostile camps, or bodies of troops in the field to say nothing of battleships at sea, will be so limited as to have no material effects on the issues of a campaign.”

In the skies over World War I battlefields, first as observation platforms, then as war machines, this thesis was proven wrong. Air-to-air combat was a natural extension of the aircraft as an observation platform. Soon, aerial observers flying over the enemy’s lines to observe realized that they could as easily drop something that exploded. Tactical bombing was born.

Tactical bombing, simply stated, is aerial bombardment of enemy targets, such as troop concentrations, airfields, entrenchments, and the like, as part of an integrated air-land battlefield action at or near the front. Tactical air power is generally used toward the same goals as, and in direct support of, naval forces or ground troops in the field.

Naturally, there were some far-sighted air power theorists who began imagining that aviation might potentially be deployed in such a way as to have “material effects” beyond the battlefield, thereby shaping the course and outcome of the war itself. This is what came to be known as strategic air power.

Strategic air power, in contrast to tactical air power, seeks targets without a specific connection with what is happening at the front. Strategic air power is used to strike far behind the lines at the enemy’s means of waging war, such as factories, power plants, cities, and, ultimately, the enemy’s very will to wage war. Strategic aircraft naturally differ from tactical aircraft in that they have a much longer range and payload capacity—certainly more than the average 1914 aeroplane. It was not until around the time of World War I that aviation technology had developed to the point where such aircraft were practical.

One of the original pioneers of strategic air power was a Russian engineer and aviation enthusiast named Igor Sikorsky, who would amaze the world 30 years later with the first practical helicopters. His 1913 aircraft, named Ilya Mourometz after the tenth-century Russian hero, was the world’s first strategic bomber. In the winter of 1914–1915, a sizable number of these big bombers were in action against German targets. The payload of each bomber exceeded half a ton, and with a range of nearly 400 miles, they were able to hit targets well behind German lines. After initial victories, the Russian army was, by 1917, defeated on the ground; the Tsar had abdicated, and the events leading to the Russian Revolution were rapidly underway. The Ilya Mourometz had been successful in what it did, but it played only the tiniest part in one of mankind’s biggest dramas.

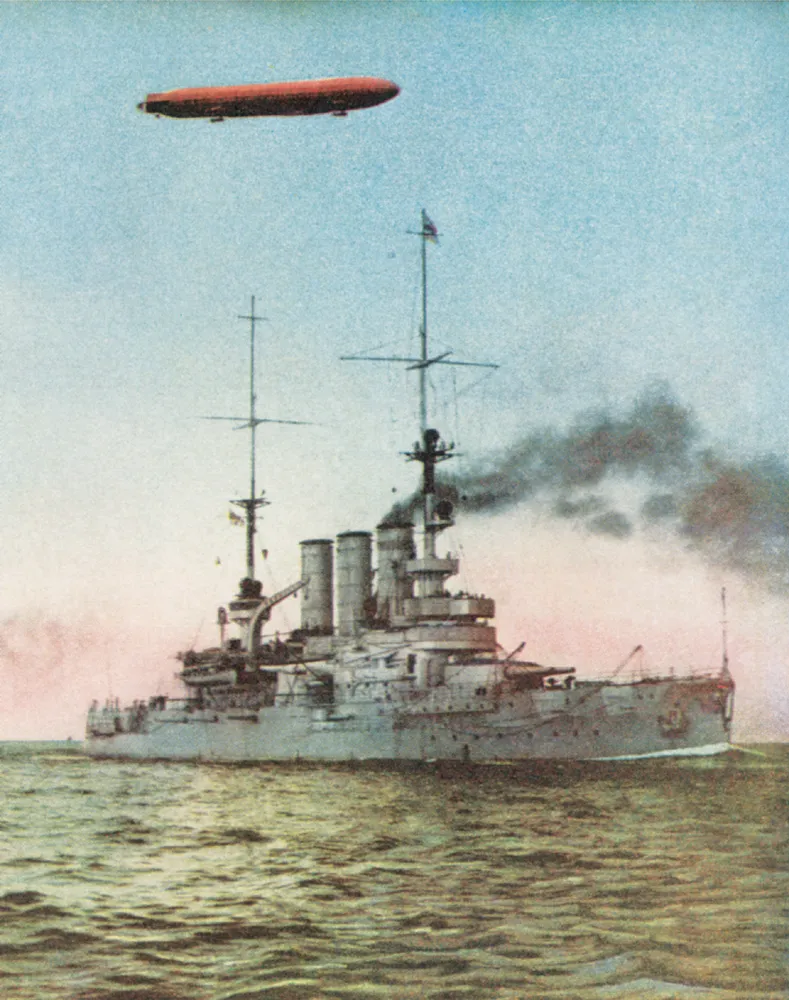

Strategic air operations on the Western Front were soon to follow those in the east, with British aircraft launching strikes against German positions in occupied Belgian coastal cities in February 1915. The Germans countered with zeppelin attacks on Paris and on British cities as far north as Newcastle. By 1917, the Germans were using long-range, fixed-wing Gotha bombers against London. In April 1918, shortly after being established as an independent service, Britain’s Royal Air Force (RAF) conducted a series of raids on German cities in the Ruhr and even ranged as far south as Frankfurt, though these raids were more strategic bombing experiments than a strategic bombing offensive. A full-scale strategic air offensive against Germany was scheduled for the spring of 1919, with Berlin on the target list, but the war ended in November 1918 with the plan untried.

Though the intervention of the United States manpower in World War I may have been of pivotal importance to the Allies, American involvement in the air war was not extensive. Nevertheless, strategic air power made an impression on the commander of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) air units in the war, Col. William Lendrum “Billy” Mitchell. He became the first major American exponent of strategic airpower, but his ideas were never implemented during the war. Strategic bombing, though experimental in British and French doctrine, was not yet accepted by the American military establishment at all.

After the war, Mitchell argued that strategic bombers were cheaper to build and operate than battleships and that they could be used faster, and more easily, to project American power wherever it might be needed around the world. He raised hackles in 1921 when he told Congress that his bombers could sink any ship afloat. To prove him wrong, the Navy agreed to let him try out his theories on some German warships they had inherited at the end of the war that needed to be disposed of. They didn’t think he could do it, but in July 1921, he proved them wrong, sinking several vessels, including the heavily armored battleship Ostfriesland. Mitchell had dramatically proven his point, but both the U.S. Army and U.S. Navy remained officially unconvinced.

Mitchell’s undoing was an unrelated incident in 1925, when, after the loss of life from the crash of the Navy dirigible Shenandoah, Mitchell called the management of national defense by the war and navy departments “incompetent” and “treasonable.” Mitchell was court-martialed, convicted, and drummed out of the service on half pension. He died in 1936, just a few years short of seeing strategic air power play a key role in the Allied victory in World War II.

Nevertheless, even before the death of Billy Mitchell, the proponents of the still-unproven concept of strategic air power had risen to places of influence within the major air forces of the world. In both Britain and the United States, large, four-engine heavy bombers were in development, while in Germany, air power in general had been fully integrated into battlefield doctrine. When World War II began, the Germans stunned military planners everywhere with the effectiveness of their blitzkrieg (“lightning war”) doctrine, in which tactical air power worked closely with rapidly moving mechanized ground forces.

Beginning in August 1940, the German Luftwaffe undertook the world’s first major strategic air campaign, the Battle of Britain. The idea was to bring Britain to its knees solely through the use of an air assault on cities and industrial targets. The campaign ultimately failed, but there was no one who understood more how narrowly it failed than the strategic planners in the Royal Air Force. For them, and for the world, the Battle of Britain demonstrated the potential of strategic air power.

When the United States entered the war against Germany alongside Britain in 1941, a key element of Allied planning was a coordinated strategic air offensive against Germany. The creation of a large bomber force capable of a major air campaign against German industrial targets was a key objective of Allied planning in 1942. By 1943, enough aircraft were available for a Combined Bomber Offensive, which was formally begun in June 1943. Sustained air attacks against Germany were made on an almost daily basis by the RAF Bomber Command and the USAAF Eighth Air Force, operating from bases in England, and by the USAAF Fifteenth Air Force, operating from bases in Italy.

The stated objective, which provides a good definiti...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Contents

- Introduction: The Most Formidable Expression

- Chapter 1: The Origins of Strategic Air Power Doctrine

- Chapter 2: Boeing Bombers Before the Stratofortress

- Chapter 3: The Strategic Air Command and a Jet Bomber Fleet

- Chapter 4: What We’ve Been Waiting For

- Chapter 5: Production and Model Evolution

- Chapter 6: The Strategic Air Command and Other Stratofortress Missions

- Chapter 7: War in Southeast Asia

- Chapter 8: Back to the Cold War

- Chapter 9: A Storm in the Desert

- Chapter 10: A Decade of Changes

- Chapter 11: Twenty-First-Century Warrior

- Chapter 12: Back to the Future

- Appendix 1: Specifications by Stratofortress Model

- Appendix 2: Stratofortress Production by Model and Block Number

- Appendix 3: Stratofortress Combat Wings and Assigned Squadrons

- Bibliography

- Index

- Copyright Page