![]()

In February 1861 the president-elect was late for an appointment. The gentlemen who were waiting for him, Norman B. Judd, a member of the Illinois Senate, and Herman Kreismann, a prominent Illinois Republican who had campaigned for Lincoln among German-speaking voters, were surprised—in general, Lincoln was a punctual man. As time went by and Lincoln still did not appear, Kreismann volunteered to walk over to the hotel where the Lincolns were staying to see what the cause of the delay was.

He entered the Lincolns’ room to find Mary Todd Lincoln in the throes of a shrieking tantrum. Kreismann was shocked by Mrs. Lincoln’s conduct and embarrassed to have walked in on such a disturbing family scene. Lincoln tried to explain, “She will not let me go until I promise her an office for one of her friends.”

The acquaintance who was the cause of Mary Lincoln’s fit of temper was Isaac Henderson, publisher of the New York Evening Post. Henderson and Mary scarcely knew each other, but there were rumors circulating among office seekers that Mrs. Lincoln was taking an active role in selecting who should have government jobs in the Lincoln Administration. Through newspaper stories about the new first lady it was already well known that Mrs. Lincoln had expensive tastes, and that gifts delighted her. Isaac Henderson wanted a post in the New York Customs House, so he wrote to Mary Lincoln, asking her to put in a good word for him with her husband. As a token of his esteem, he sent along some diamond jewelry.

Lincoln gave in to his wife; he appointed Henderson to the Customs House. It was not one of his best appointments: In 1864 Henderson was arrested and tried for corruption. He was charged with demanding kickbacks from contractors, and that one such payment totaled $70,000. In the months leading up to his trial there were rumors in New York City that Henderson had tried to buy members of the grand jury, prospective witnesses, even the district attorney. Henderson’s acquittal proved to many people in government that he had corrupted the court just as he had once corrupted First Lady Mary Lincoln.

The Henderson matter was among the first instances of Mary Lincoln demanding that her husband give government jobs to men who, in one way or another, had won her good opinion. Her intentions may have been good—she did want to be one of Lincoln’s trusted political advisors—but her susceptibility to bribery made her a political liability.

THE EDUCATION OF MARY TODD

The future Mrs. Lincoln was born Mary Ann Todd on December 13, 1818, in Lexington, Kentucky. She was the fourth child of Eliza Parker and Robert Todd, who were second cousins. Parkers and Todds had fought for American independence, and then fought Native Americans to carve towns out of the Kentucky wilderness. They prospered in the new land, and became prominent, respected members of the emerging Kentucky society. The Todds, for example, were among the founders of Lexington and of the town’s Transylvania University; pride in the college inspired the citizens of Lexington to call their town “the Athens of the West.”

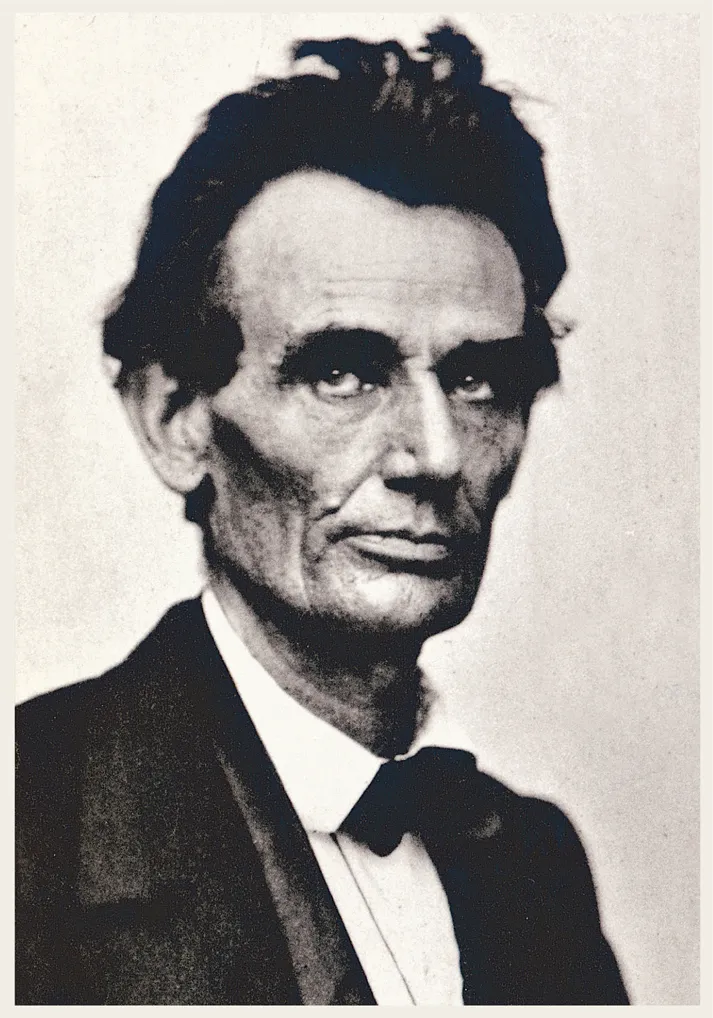

THIS PHOTO OF LINCOLN, TAKEN DURING THE PRESIDENTIAL CAMPAIGN OF 1860, REVEALS HIS GAUNT, RAW-BONED APPEARANCE, IN STARK CONTRAST TO HIS PLUMP AND STYLISH WIFE. AS MARY TOLD A FAMILY FRIEND, LINCOLN “IS TO BE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES SOME DAY; IF I HAD NOT THOUGHT SO I NEVER WOULD HAVE MARRIED HIM, FOR YOU CAN SEE HE IS NOT PRETTY.”

Mary grew up in a handsome 14-room brick house, built in the elegant Georgian style. Robert Todd owned several slaves, including Mammy Sally, who cared for the Todd children.

At age six Mary suffered the first of the many tragedies that would haunt her life: Her mother died after giving birth to her sixth child, Mary’s brother George. Seventeen months later Robert Todd married a woman from Frankfort, Kentucky, named Elizabeth Humphreys. Almost from the start animosity sprang up between the Todd children and their stepmother. Robert and Elizabeth had nine children together, and although for the most part the half-brothers and half-sisters got along amicably, Eliza’s children never warmed up to Elizabeth Humphreys. Years later Mary would describe her childhood after the death of her mother as “desolate.”

Her refuge was school. After attending elementary school, Mary’s father enrolled her in Mentelle’s for Young Ladies, an academy operated by French emigrants, Paris-born Augustus Waldemare Mentelle and his wife, Charlotte Victorie Leclere Mentelle. The academy was only a mile and a half (2.4 km) from the Todd house, and the family’s driver, Nelson, could have taken Mary back and forth in a carriage every day, but Mary boarded at Mentelle’s. It was her escape from an unhappy home life.

Thanks to Madame Mentelle, she became fluent in French, which Mary spoke with a Parisian accent. She read widely in literature and history. Theatricals were part of life at the school, and Mary performed in several plays—she was dramatic by nature. Furthermore Madame Mentelle passed along to Mary her outlook on life, particularly an admiration for aristocrats and women of an independent frame of mind. Robert Todd approved of well-educated, spirited women (Mary remained in school years longer than most of her friends), and he encouraged Mary to express herself. She was especially interested in politics and on several occasions she discussed the issues of the day with one of her father’s friends, Senator Henry Clay.

As she approached her late teens Mary Todd developed into a well-educated, sophisticated, well-read young woman, who was not afraid to express her opinion on any subject.

THE BELLE OF SPRINGFIELD

In 1836, 17-year-old Mary graduated from Mentelle’s and announced that she was leaving Lexington to live with her older sister Elizabeth and her brother-in-law Ninian Edwards in Springfield, Illinois. Her father was not terribly sorry to see her go, as it meant an end to the violent quarrels between Mary and her stepmother.

The Mary Todd who arrived in Springfield stood five-feet-two-inches tall (1.57 m). She possessed lively blue eyes and a lovely complexion. She was a bit plump, and her chin was a touch prominent, but she had a sharp wit, a good mind, and a degree of cultivation that was rare in a rawboned prairie town like Springfield.

If Mary had come husband-hunting, Springfield was the place to be. In 1836, there were 24 percent more men than women in Sangamon County (where Springfield was located). Furthermore, the Edwards’s house was the center of Springfield’s high society, where Mary would meet gentlemen from the best families as well as up-and-coming young men such as her cousin John Todd Stuart’s law partner, the gangly, socially awkward 27-year-old Abraham Lincoln.

Mary and Abraham were both Kentuckians, but the similarity ended there. She grew up in luxury, he was born in a dirt-floored log cabin. As a child she had every comfort and security; he spent his boyhood doing strenuous physical labor and pinching pennies. She had attended a French-style academy, he was almost entirely self-educated.

They shared a love of literature, particularly poetry. And they were both intensely interested in politics. Mary had come to Springfield to start a new life, Abraham had come there to make something of himself.

Mary had plenty of suitors, at least one of whom was a good friend of Lincoln’s. At a party William Herndon asked Mary to dance; as he led her around the floor, he made what he thought was a clever remark—that Mary “seemed to glide through the waltz with the ease of a serpent.” Mary Todd stopped dancing, declared that she didn’t like such a comparison, then walked off, leaving Herndon alone and embarrassed on the dance floor.

In addition to all her assets, Mary possessed a serious liability—a Springfield neighbor said that Mary was “subject to...spells of mental depression.” Mary’s mood swings could be violent and unpredictable—one moment she was laughing and vivacious, the next sunk in deep depression. Emotionally she was, as a saying of the time put it, always either in the garret or in the cellar.

In 1840 it became clear to Elizabeth Todd Edwards that Mary preferred Lincoln above all her other suitors. Elizabeth was not convinced that Lincoln was a suitable match for her sister. She described him as “a mighty rough man...dull in society...careless of his personal appearance...awkward and shy.” No letters or other documents survive to tell us the details of Lincoln’s courtship of Mary Todd, all we know is that sometime in 1840 they became engaged. Then, late in 1840, for unknown reasons, Lincoln broke off the engagement. But in 1842 they were reconciled and during the first few days of November 1842 they surprised their family and friends by announcing that they planned to marry on November 4. The ceremony took place before a handful of guests in the parlor of the Edwards’s house.

MARY LINCOLN ADORED FLOWERS AND ESPECIALLY ENJOYED WEARING ELABORATE ARRANGEMENTS IN HER HAIR AND ON HER GOWN ON FORMAL OCCASIONS. SHE WORE THIS FLORAL CROWN DURING THE CELEBRATIONS OF HER HUSBAND’S INAUGURATION AS PRESIDENT.

“WE HAVE WON!”

In later years Lincoln’s friends concluded that his marriage to Mary Todd was the making of him. By nature he lacked energy and drive, but Mary recognized his gifts and as Elizabeth Todd Edwards said, “pushed him along and upward—made him struggle and seize his opportunities.” Lincoln’s best friend, Joshua Speed, recalled, “Lincoln needed driving—(well, he got that).” And in the late 1840s Mary stated candidly to Ward Hill Lamon, a friend of the Lincoln family, that her husband “is to be president of the United States some day; if I had not thought so I never would have married him, for you can see he is not pretty.”

Mary became Lincoln’s most zealous political supporter. She even cut off friends if they disagreed with her political views. If Lincoln suffered a setback he took it in stride as part of the give-and-take of politics, but Mary could not exercise such restraint: she denounced Lincoln’s political rivals as “dirty dogs... connivers... dirty abolitionists.” Her confidence in her husband’s political career never flagged. Once, when Lincoln was depressed about his prospects for national office, he lamented, “Nobody knows me.” Mary replied, “They soon will.” Even William Herndon, Lincoln’s law partner whom Mary had shamed on the dance floor twenty years earlier, showed grudging respect for Mrs. Lincoln’s tireless advancement of her husband’s career, although Herndon put it in a nasty way. Mary Lincoln, he said, was “like a toothache, keeping her husband awake to politics night and day.”

In 1859 and 1860 when Lincoln was campaigning for the Republican Party’s nomination as president, Mary found herself courted by political power brokers. To her delight, newspapers published articles about her. A reporter from the New York Tribune praised Mary as “amiable and accomplished...vivacious and graceful...a sparkling talker.”

Mary blossomed in the spotlight. She welcomed journalists into her home where she spoon-fed them lively, colorful copy, including the story of her friendly wager with her neighbor, Mrs. Bradford: if Lincoln won the presidency, Mrs. Bradford would present Mary with a pair of new shoes, and Mary would do the same if the Democrats’ candidate, Stephen A. Douglas, won the White House. When Republican operatives called at the Lincoln home, Mary sat with them, assessing candidly the chances of office seekers who even before Election Day were jockeying for posts in the Lincoln Administration.

On November 6, 1860, Lincoln spent the evening in the Springfield telegraph office waiting for the election returns. When the wire carried word of his victory, he hurried home, crying, “Mary! Mary! We have won!”

“MAKING AND UNMAKING POLITICAL FORTUNES”

Mary had settled ideas about herself as first lady. She would entertain in her own right. She would equal if not surpass the most fashionable ladies of Washington. She would be her husband’s political partner. And she would expect special favors to be granted her as first lady (a title invented for her by a reporter from the Times of London). When Mary went on a train trip, for example, most railway officials waived the customary fare. But when one railway asked her to purchase a ticket just like any other passenger, Mary bristled. She insisted that her eldest son, Robert, speak to the railway agents, which he did: “The Old Lady,” he said, “is raising hell about her passes.”

Nonetheless, once she arrived in Washington, D.C., Mary tried to assert that she was a conventional wife of a public figure, unwilling to step into the spotlight. “My character is wholly domestic,” she declared to James Gordon Bennett, editor of the New York Herald. But a reporter for the New York Times revealed her real character: “Mrs. Lincoln is making and unmaking the political fortunes of men and is similar to Queen Elizabeth in her statesmanlike tastes.”

And it was not just office seekers who sought Mary Lincoln’s good opinion: In 1861 several New York store owners presented the first lady with a gleaming black barouche and four matching black carriage horses, with a note that the horses could be exchanged “if Mrs. Lincoln preferred another color.” The unspoken message of the gift was that the merchants hoped when Mary shopped in New York City—and she adored shopping in New York City—she would patronize their stores. That President Lincoln knew about the carriage, who had sent it, and why they had sent it, clashes with our image of “Honest Abe.” Mary Lincoln biographer Jean Baker assures her readers, “Accepting the barouche was hardly a conflict of interest, at least not as understood by freewheeling nineteenth-century politicians.”

Of course, Lincoln had his limits. When the king of Siam sent magnificent gifts that included diamonds and elephants, he assumed he was presenting them to Lincoln personally, as a fellow sovereign. Lincoln did not know what to do with the elephants and would not dream of pocketing the diamonds, so in his thank-you note to the king he expressed his gratitude but also explained, “Our laws forbid the President from receiving these rich presents as personal treasures. They are therefore accepted in accordance with your Majesty’s desire as tokens of goodwill and friendship in the name of the American People.” Mary Lincoln had no such scruples.

In spring 1861 George Denison, a New York lawyer connected to the Lincolns’ banker in Springfield, Robert Irwin, petitioned Mary to help him secure the post of naval officer in charge under the collector of customs of the port of New York. To guarantee Mary’s help he sent her a carriage and opened for her a credit line of $5,000, which she could use in New York on her next shoppin...