Introduction

Yesterday you learned that you possess rights. In fact, the ombudsperson explained that a UN convention declares all young people possess rights, no matter where they live. The ombudsperson said that every child has the right to be safe, to grow up with food and an education, and to live with their families. You had never heard about these rights at your previous school, let alone your previous country. You wonder what other rights the convention says belong to you and your sister. How do you find rights that belong to you?

Where do we find children’s rights? Are children’s rights socially constructed, or are they separate from social interaction (Gregg 2011), part of the natural order? Do children’s rights exist on their own or because governments endow children with rights (Freeman 1998)? The lattermost question continues to rise to the top of battles over young people’s rights. It is raised when children’s rights seem to conflict with the rights of their parents. Can a young person choose her religious beliefs or must she attend church because her parents insist? What recourse do young people have when government leaders reduce commitments to social programs that appear to weaken children’s rights (Dwyer 1994; Hertel and Libal 2011), such as cutbacks to public education (but not to public pensions)?

A touchstone of children’s rights is the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC). Adopted in 1989, this UN treaty is often considered the most widely supported human rights treaty, with only the United States not having ratified this convention (United Nations 2020). Through UNCRC ratification, national governments not only indicate their support of children’s rights, they state their intention to ensure that children’s rights matter. This chapter examines major international treaties that have shaped children’s rights. What do these treaties say about their rights?

Children’s rights are sometimes characterized as forming a bundle of rights (Barnes 2012). A bundle of rights means that the rights are interrelated and interdependent. Rights work together – a collection of rights that together support and reinforce each other. Do young people possess a bundle of rights? Experts of human rights, including scholars and policy makers, say that possession of a bundle of rights is necessary to an individual’s membership in society (Isin and Wood 1999). Is this conception applicable to young people: must young people possess a bundle of rights to be members of their society? If so, in practice, do young people possess a bundle of rights they can exercise (Fortin 2009; Mortorano 2014)?

Foundations of children’s rights

From where do children’s rights come? Foundations of children’s rights are centuries – even millennia – old. These foundations shape contemporary notions of children’s rights and how children’s rights work. Young people’s rights are articulated in religious texts. The Torah’s Book of Deuteronomy, chapter 24, verse 17, provides protection and safeguards to young people, placing responsibility not only on parents, but on strangers. The Bible’s New Testament attributes statements to Jesus that support children’s rights to pursue their beliefs and live according to what their conscience directs. The Gospel of Mark, 10:14, states, “But when Jesus saw it, he was indignant and said to them, ‘Let the children come to me; do not hinder them, for to such belongs the kingdom of God.’” Other New Testament Gospels, Matthew 19:13–14 and Luke 18:15–17 ascribe this statement to Jesus. Experts interpret the Koran as saying that parents are obligated to provide spiritual and material well-being to their children, as well as that children possess the right to receive fair shares of property from their parents. Children’s rights and who owes duties to young people are identified in these religious texts. Parents are obligated to fulfill their children’s rights, including spiritual education, as well as providing food and resources necessary to their child’s education. Parents are not the only people who are obligated to ensure children’s rights are implemented. Strangers, according to the Book of Deuteronomy and the New Testament, hold duties to young people, such as their protection. Responsibilities of ensuring young people’s rights are implemented extend beyond the child’s family. These ancient propositions are found in today’s societies.

We can turn to philosophical traditions to find insights into children’s rights. The philosopher, teacher, and politician Confucius concentrated on young people’s well-being when it came to their rights. According to Confucius, if a father did not support his children’s welfare, his children were entitled to disobey him (Huang 2013: 132). Aristotle’s notion of the state continues to influence contemporary forms of and approaches to governance. At the heart of Aristotle’s state is the male citizen (Politics, book I, part XII). The male citizen is central to how a state works with the community and with the family, including relationships within the household. According to Aristotle, household relationships are organized distinctly around husband–wife and father–children. The husband is expected to rule constitutionally over his wife such that he treats his wife appropriately, so that she does not choose to vote him out of office. On the other hand, the father is to rule over his children as a king rules over his subjects. In Aristotle’s conception, the state, consisting of male citizens, will intervene into the family home if the father does not govern his children correctly.

While Aristotle’s conception of the state and politics shapes current approaches to governance, his ideas are not without criticism. A key objection is Aristotle’s idea that male citizens, acting as the state, will intervene into the family home to challenge another male citizen’s actions as husband/father (Benhabib 1999; Gobetti 1997; Minow 2003; Romany 1993). Given that the state consists of male citizens, these experts challenge the possibility that the state will intervene into the family home. More precisely, they contend that male citizens will not challenge another male citizen’s governance, even when male citizens fail to govern properly. Critics (Gobetti 1997: 31) challenge structures of Aristotle’s state, accusing this state as based on and promoting misleading assumptions on utilities of rights in private domains for groups whose members do not consist of male citizens, such as children. Today, governments of many societies fail to intervene into family homes to enforce young people’s rights, even in cases of domestic violence (Minow 2003). Given the common application of Aristotle’s state, we may question whether contemporary governance structures are set up in ways that permit violations of children’s rights in private domains (Gran 2009).

Despite influences of religious beliefs and philosophical traditions, not until the late 1800s did children’s rights receive significant attention. Widespread industrialization brought migration from rural to urban communities, and shifts from agricultural to industrial employment (Tilly 1983). While young people may have previously worked on farms, increasingly they were employed in factories. Attention was drawn to conditions in which young people were growing up (Tuttle 2018). Associations of people who shared interests in common causes were founded. While the American Humane Society – currently the American Humane – had concentrated its efforts on protecting animals, it began to advocate for the welfare of young people. The American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals took on a case of child abuse in 1873 (Pearson 2011). Pearson (2011), in her terrific book, The Rights of the Defenseless, describes the organization’s efforts to establish legal protections for children’s welfare. Pearson (2011: 4) demonstrates how the American Humane Society worked to establish “cruelty” to children as a problem that required changes in how societies function.

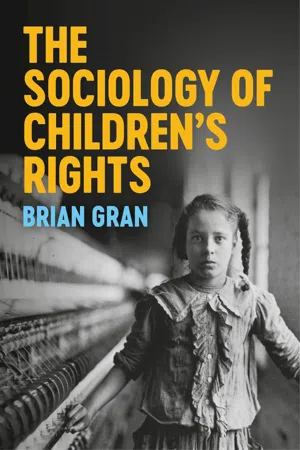

New kinds of evidence influenced perceptions of humanity and children’s lives. Around the time the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals was advocating for protections for children, photographers documented harsh realities in which young people were living and working in the United States. You may have come across the work of two notable photographers whose work changed our notions of childhood: Jacob Riis and Lewis Hine. Born in Denmark, Jacob Riis, who lived from 1849 to 1914, was a journalist who used his work to bring about social ref...